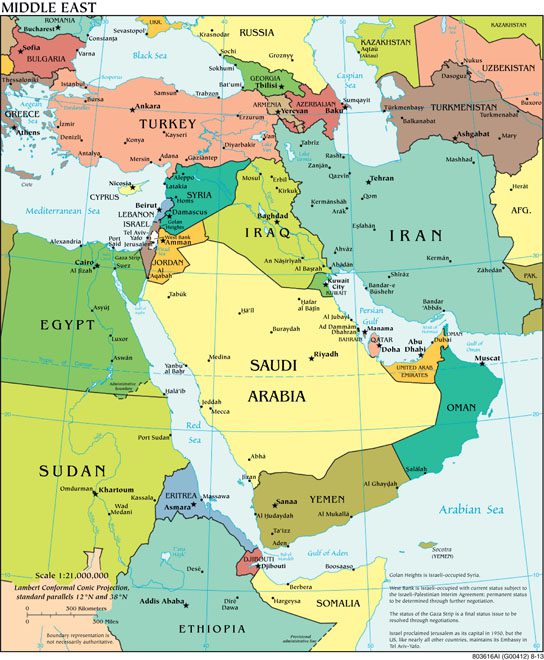

(Wikimedia Commons public domain)

Knowing what to call the region often known as the “Middle East” is surprisingly difficult.

What is it east of? Morocco, which many people consider Middle Eastern, is west of France. And why should Paris and London be considered the center of the world, anyway?

And what is “the West?” Is it a geographical region or a cultural given? Is Australia part of it?

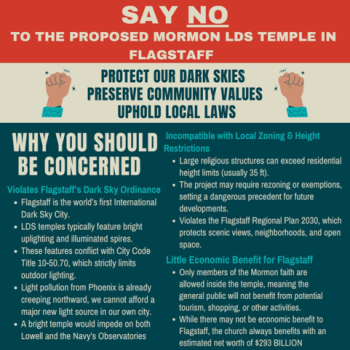

Of course, some don’t consider Morocco part of the Middle East. (See the map above.) But there is a fundamentally important cultural continuum from Morocco clear across to at least Iraq, and no impassable geographical barriers from east to west.

“Far Eastern” is fairly clear. It’s East Asia. China and Japan, for instance. Korea, too. Thailand. Cambodia and Vietnam.

But is there any difference between the “Middle East” and the “Near East”? My impression is that, today, there really isn’t. I received my Ph.D. with an emphasis in Arabic studies from a Department of Near Eastern Languages and Cultures. I teach Arabic and Arabic studies in a Department of Asian and Near Eastern Languages, but our overall program at BYU is Middle East Studies (Arabic). And if I were teaching the same classes at the University of Utah, I would be teaching in the Middle East Center. Listening to myself, I find that I use them interchangeably and with approximately equal frequency.

My sense, though I haven’t really researched the matter, is that there used to be a continuum, and a distinction, from Far Eastern through Middle Eastern (perhaps the Indian subcontinent and Iran, etc.) to Near Eastern (e.g., Egypt over to Morocco). If so, however, such differences have been lost.

And what, actually, is in the “Near East” or “Middle East”? I’ve seen some maps that included Pakistan and even Greece but excluded Tunisia and Morocco and perhaps even Algeria.

The great historian of Islam Marshall G. S. Hodgson fought valiantly to introduce greater terminological exactness into the field. But he didn’t have much success. I myself really like his distinction between Islamic (of, or pertaining to, the religion itself) and Islamicate (of, or pertaining to, the culture in which Islam is dominant, but not necessarily religious at all — e.g., Islamicate metalwork). That a mosque is an Islamic building is obvious, of course. But why should a palace, say, or an Arabic or Persian lyric poem necessarily be termed “Islamic”? Is the White House a Christian building in even remotely the same sense that the cathedrals of Cologne or Chartres are Christian? C. S. Lewis is a Christian writer, certainly. So is Dante. So is Milton. But is Ernest Hemingway? Is F. Scott Fitzgerald? Ezra Pound? Goethe? Nietzsche?

I can see, though, why Hodgson’s proposal of “the Nile-to-Oxus region” didn’t really catch on.

And the battle is probably lost. Even “Middle Easterners” have adopted Middle East and, I think to a considerably lesser degree, Near East for themselves.

Arabs, for example, live in, and have a major newspaper called, Al-Sharq al-Awsat (“The Middle East”). Sometimes, they refer to al-sharq al-adnaa (“the Near East”). And people such as I are engaged in al-diraasaat al-sharq al-awsatiyya (“Middle Eastern studies”).

Oh well.

Posted from Newport Beach, California