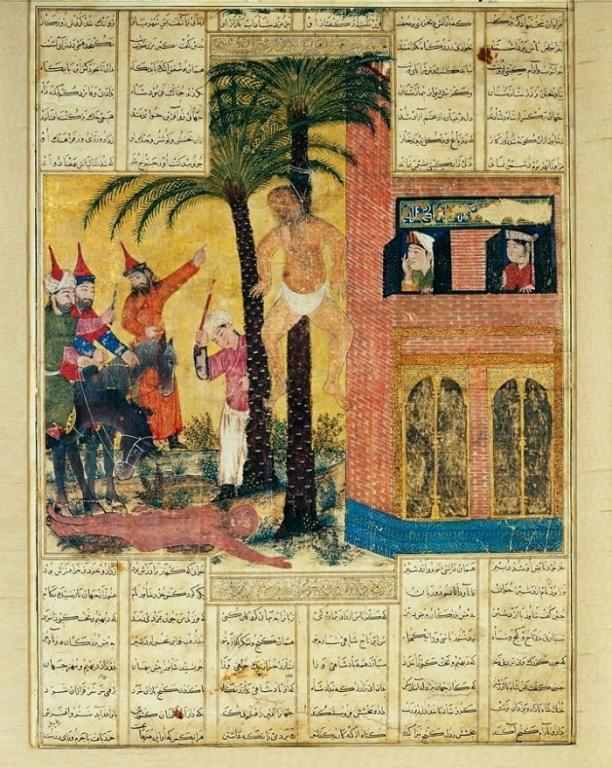

(Wikimedia Commons public domain image)

Bill Hamblin and I published this article in the Deseret News very nearly five years ago, on 7 March 2014:

Although Manicheism — the religion founded by the Mesopotamian prophet Mani — is dead, its influence still continues in subtle and indirect ways.

Mani was born in A.D. 216 near the modern city of Baghdad in Iraq, which was then part of the Persian Empire. Although a Persian, Mani was raised in a Gnostic Christian sect known as the Elkesaites, whose founder, Elkesai, was a Christian prophet living in Jordan around A.D. 100. His followers believed that a heavenly book of scripture had been revealed to him as a supplement to the writings of the New Testament.

At the age of 12, Mani claimed to have received a vision from his angelic “celestial twin,” who revealed heavenly secrets to him. As Mani himself described his first vision: “In the reign of King Ardashir (of Persia) the Holy Spirit came down and spoke to me. He revealed to me the hidden mystery, hidden from the ages and the generations of Man: the mystery of the Deep (underworld) and the High (heavens), the mystery of Light and Darkness, the mystery of the (apocalyptic) Contest, the War, and the Great (Final) War. The Holy Spirit disclosed to me all that has been and all that will be.”

At age 25, Mani left the Elkesaites, founding his own new religion. In the following years, he preached in India and Iran with some success, eventually converting the brother of the Persian emperor Shapur, who introduced Mani at the imperial court.

However, his success made him a threat to the Zoroastrian state religion of the Iranian empire. After the emperor Shapur’s death, Mani was imprisoned as a dangerous heretic. In 276, he was martyred by being flayed alive under the order of the famous Zoroastrian High Priest Kirder.

Mani believed that he was the last and greatest of the prophets, successor to the founders of the three great religions of Iran in his day: Zoroastrianism, Buddhism and Christianity. He described himself as an apostle of Jesus, teaching the true original form of Christianity.

According to Mani, there is a fundamental dualism between spirit and matter, light and darkness. The pristine world created by God was a world of light and spirit, but when the powers of darkness overcame the first man, the spirits of light became imprisoned in the chains of dark matter. These sons of light need to be freed from darkness in order to ascend back to the presence of God. This liberation from the bonds of material darkness was the goal of Mani’s revelation, which he called heavenly knowledge (gnosis).

Mani’s attempt to integrate Christianity, Buddhism and Zoroastrianism led to some interesting twists of doctrine, such as medieval Turkish Manichaean texts that speak of the nirvana of the Buddha Jesus on the cross.

Mani’s followers were organized into two groups: the Elect, who were expected to live the higher law, and the Hearers, who were followers of a lesser law. The Elect lived by the “three seals”: that they would abstain from wine and meat, that they would harm no living thing, and that they would live in celibacy so as not to imprison new spirits of light in the bondage of matter. The Hearers followed and supported the Elect, but were not required to live these three higher laws.

Perhaps Mani’s most important convert was the famous Catholic theologian Augustine (A.D. 354-430), who was a Manichean for nine years before his conversion back to Christianity at age 33. Thereafter, Augustine wrote a book condemning Manicheism.

But Augustine’s doctrine of the fall — which became normative for Catholics — was in part his reaction to Manichean thought. Later, medieval Christian heresies such as the Paulicians, Bogomils and Cathars were all influenced by Manichean ideas.

At its height in the sixth and seventh centuries, Manicheism was probably the most widespread religion in the world, with members found from Spain to India and China.

However, Manicheans were almost everywhere in the minority. Suffering religious persecution under increasingly intolerant kingdoms, their religion eventually disappeared.

Manicheism was most successful among the nomads of Central Asia, where it was declared the official religion by the king of the Uigur Turks in 762, surviving there until the 16th century. Today, only a few followers of neo-Gnostic New Age movements still revere the writings of Mani as scripture.

Nonetheless, subtle influences of his ideas can be found throughout the history and doctrines of both Christianity and Islam.