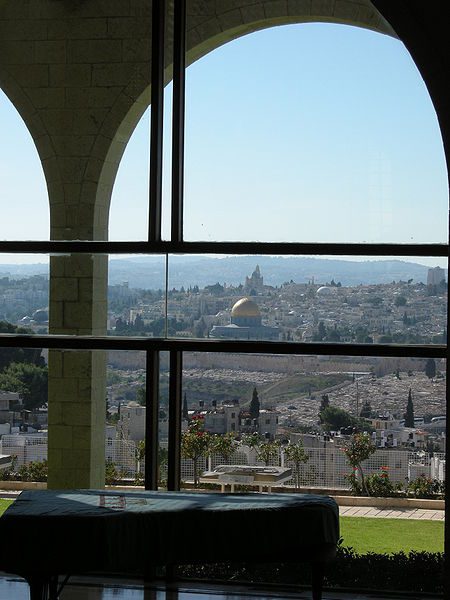

More, regarding the construction of the most visible Latter-day Saint landmark in the Middle East:

On 4 March 1987, occupancy permits were issued for the not quite-completed center and, on the recommendation of both the Church’s legal staff and its local lawyers, students and faculty immediately moved into the twenty-million-dollar structure. On the eighteenth of May in the following year, President Jeffrey Holland of Brigham Young University signed a forty-nine year lease for the land on which the building sits, with a renewal option for another forty-nine years beyond that. He again committed the university and the Church to refrain from any kind of proselyting “as long as such activity is not allowed by the government of Israel.”

Not all critics of the center and the Latter-day Saints were silenced by the fact that students had actually occupied the building. For years, they were still on the lookout for any sign of missionary activity on the part of students, faculty, or staff at the center. Students are required even today to sign a pledge that they will not engage in such activity. They are even told to refer people who ask questions to generally available encyclopedia articles or to online resources rather than themselves engaging in conversations on religion. For one thing, the person inquiring might be some kind of provocateur seeking to create an incident. An oversight committee of Israeli officials, created as part of the agreement that permitted the construction of the center, must approve concerts, organ recitals, and public lectures in the building, after screening them for any evidence of secret missionary agendas. (The committee’s jurisdiction extends only to nonacademic functions in the center; university and Church officials insisted that purely academic matters remain internal.)

The limitations within which the Church and its members have agreed to work in Israel (and occasionally elsewhere in the Near East) sometimes create ironic situations. It is only in the Near East that I have been taught, and have taught others, that it is part of a Latter-day Saint’s religious duty not to proselyte and, indeed, to avoid speaking on religious subjects with the local population. An illustration of the kind of awkwardness of which I speak occurred in my own personal experience. When, a few years ago, some of us at Brigham Young University were laying the groundwork for an intensive Arabic language program to be conducted at the Jerusalem Center, we were not yet certain that there would be enough interested students on our own campus to make the program worthwhile. It would be necessary, we thought then, to recruit superior students from other universities as well. So we tentatively decided that we would circulate advertisements for our program to appropriate departments at other schools and place them in several journals dealing with Near Eastern studies. But, someone suddenly exclaimed, what if a Jewish student applies to participate? Many of the best students of Arabic in the United States at any given time are, after all, Jewish. They have a natural reason for interest in Near Eastern fields and often have a head start on the study of other Semitic languages because of a knowledge of Hebrew. Our critics in Israel, however, would not be any the less upset with us if we seemed to be “proselyting” among American Jews instead of Israelis. Well, it was suggested, perhaps we could screen out people with “Jewish” names. But another person pointed out that such screening was illegal in the United States and probably wasn’t completely effective anyway. Some American Jews don’t have obviously Jewish names. And what if, someday, it came to somebody’s attention that we had systematically turned down Jewish applicants even when they had excellent credentials? I myself suggested that maybe, at the bottom of our ad, we could have a small eagle and a swastika, along with a note in German that no Jews need apply. Obviously, we were caught between discriminating against Jews, which was not only wrong but illegal in the United States, and not discriminating against Jews, which would eventually get us into horrible trouble in Israel. The irony that Israeli policies encouraged us to discriminate against American Jews was every bit as rich as the irony of devoutly non-proselyting Mormons. Eventually, though, we decided that the risks of recruiting students elsewhere were simply too great and gave up the idea—which, as our own students’ response soon demonstrated, wasn’t really necessary anyway.

Posted from Washington DC