(Wikimedia Commons)

I’ve begun to read The Victory of Reason: How Christianity Led to Freedom, Capitalism, and Western Success, by Rodney Stark, the distinguished sociologist of religion who taught for more than three decades at the University of Washington and then, after his retirement there, assumed a position as Distinguished Professor of the Social Sciences at Baylor University and became co-director of the university’s Institute for Studies of Religion.

This is one of two books that I will address in remarks on faith and reason at FreedomFest 2018. The other is Charles Freeman’s The Closing of the Western Mind: The Rise of Faith and the Fall of Reason.

The books make very different cases, coming to quite opposed conclusions. Whereas Freeman argues, beginning with the apostle Paul and St. Augustine, that Christianity is essentially anti-intellectual in its dismissal of worldly wisdom and “science” as “foolishness,” Stark focuses especially on Christian thinking in St. Thomas Aquinas and his successors, who emphasized reason and favored the advancement of both science and market capitalism.

The so-called Scientific Revolution of the sixteenth century has been misinterpreted by those wishing to assert an inherent conflict between religion and science. Some wonderful things were achieved in this era, but they were not produced by an eruption of secular thinking. Rather, these achievements were the culmination of many centuries of systematic progress by medieval Scholastics, sustained by that uniquely Christian twelfth-century invention, the university. Not only were science and religion compatible, they were inseparable — the rise of science was achieved by deeply religious Christian scholars. (12)

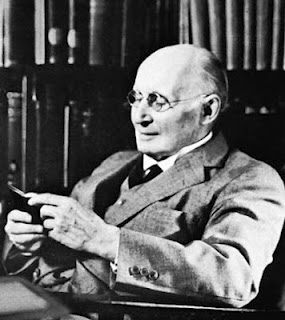

Stark calls as a witness to his claim Alfred North Whitehead, the great Anglo-American mathematician and philosopher who co-authored the landmark Principia Mathematica with Bertrand Russell between 1910 and 1913:

In contrast with the dominant religious and philosophical doctrines in the non-Christian world, Christians developed science because they believed it could be done, and should be done. As Alfred North Whitehead put it during one of his Lowell Lectures at Harvard in 1925, science arose in Europe because of the widespread “faith in the possibility of science . . . derivative from medieval theology.” (14)

As he explained: “The greatest contribution of medievalism to the formation of the scientific movement [was] the inexpugnable belief that . . . there is a secret, a secret which can be unveiled. How has this conviction been so vividly implanted in the European mind? . . . It must come from the medieval insistence on the rationality of God, conceived as with the personal energy of Jehovah and with the rationality of a Greek philosopher. Every detail was supervised and ordered: the search into nature could only result in the vindication of the faith in rationality.”

Whitehead ended with the remark that the images of gods found in other religions, especially in Asia, are too impersonal or too irrational to have sustained science. Any particular “occurrence might be due to the fiat of an irrational despot” god, or might be produced by “some impersonal, inscrutable origin of things. There is not the same confidence as in the intelligible rationality of a personal being.” (15)