Last week I was in Pittsburgh to speak on modern art and grace at the annual Jubilee conference, an event that brings 2,000 college students together to connect their faith to their work. After my presentation, a person working in campus ministry asked me how he could support two students who happen to be artists. His question revealed just how art can challenge assumptions about vocational discipleship and a theology of work in the evangelical community.

The vocation conversation in the evangelical community

The vocation conversation ranges from work-life balance, the pressures of ministry, and what vocations are “off-limits” for Christians to workplace ethics, maximizing efficiency and productivity, and leadership development, all underwritten theologically by the “cultural mandate” of Genesis 1: 28 and our role in the eschatological fulfillment of the kingdom, whether in transforming, redeeming, making, or bearing witness to culture.

Usually absent from these conversations is the work of the artist. When the artist does figure into discussions about vocation, she is romanticized to the margins. Either she is described as the mysterious producer of a theological abstraction, “beauty,” or is reduced to an outside the box vision caster whose “creativity” adds value to this or that organization. This is not an evangelical problem. It’s a cultural problem, for we are skeptical of art’s usefulness inside and outside the church.

However, I would like to suggest that artists offer an important voice in the vocational conversation, if we take the time to probe artistic practice more deeply.

Here are just a few ways that the artist’s studio can become a crucial location for rethinking vocation.

Mid-Life Crisis at 19

My two decades of experience teaching art students, both in evangelical colleges and in public universities, is that they must face crucial vocational questions of value that usually confront those of us only later in our careers. The question that a forty-five year old lawyer asks, like, “what am I doing this for?” is asked by the art student her first semester in college, when she has to justify to her parents why they should pay hundreds of dollars per credit hour for her to push paint around on a canvas with little in the way of stable job prospects after graduation. And for her entire career as an artist, she will struggle with the value of spending long hours in the studio producing paintings that undermine our culture’s presumptions, inside and outside the church, about the “use” of her work.

Who is an artist?

There are few cultural practices with less professional structure than art. There is no bar exam, no board that confers the title “artist” on a person. And so the art student, from the very beginning, must struggle with recognition and justification in an especially acute way. What makes me an artist? Does my neighbor recognize me as an artist? Educational credentials, which usually mean so much in the workforce, are not helpful in establishing a difference between one who has an M.F.A. from an Ivy League school and says, “I’m an artist” and another, who is an investment banker, paints pictures in her spare time, and likewise claims, “I’m an artist.” The artist’s vocational identity must come from elsewhere, and although the evangelical community presumes this, a lot of vocational talk still sounds a lot like baptizing our culture’s definitions of leadership and success.

The tortured artist stereotype

Edvard Munch said, “art comes from joy and pain.” And then he added, “but mostly from pain.” The myth of the tortured artist, which has a long and distinguished history, who feels more deeply, struggles with depression, addiction, and alienation puts the artist “over there” away from “us,” either on a pedestal or in the gutter. But that posture overlooks one very important reality: the artist is exactly like us. Most of our work comes from pain. We struggle with precisely the same existential problems and insecurities as Edvard Munch, we possess the same self-doubt, insecurities, and struggle with failure. Yet our vocational conversations usually prevent such admission and the important and necessary reflection that could follow.

Vocation is more than a paycheck

The discussion of vocation inside the evangelical community and beyond often limits itself to career choice and placement. Yet, for Martin Luther, vocation was much more comprehensive. It was the result of reflection on the social implications of the doctrine of justification, forming how we respond to the faith that the Word has created that enables us to love our neighbor. Vocation underwrites all of our social roles, not just the one at the office. From the beginning, art students must recognize that their calling as artists consists of more than a pursuit of a comfortable living to support a family and acquire stuff. Moreover, most art students come to understand that they will not make a living selling their work. This is the case for nearly all artists, even those who are “successful.” Many must supplement their income creatively through teaching, real estate, or other endeavors that offer the financial stability to pursue their vocations as artists without the pressure of selling their work.

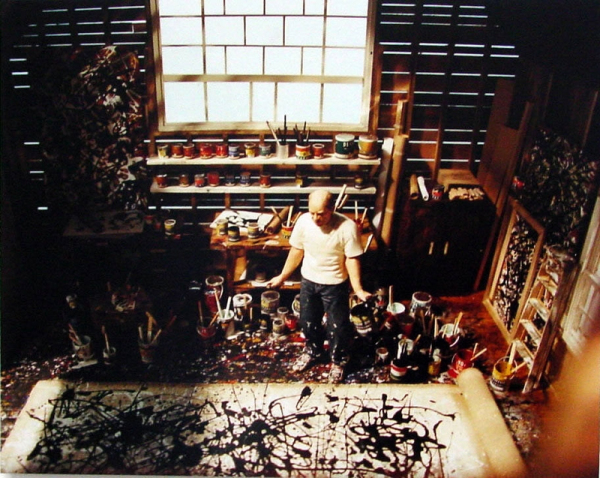

The artist’s studio as a vocational lab

The conversation in the evangelical community about vocation is important not merely for the church but for the larger culture. And the vocational implications of artistic practice are crucial for expanding its reach. The history of art, especially modern art, offers an important means by which art can contribute to this conversation, opening up new space to reflect on the Word that establishes the work of our hands (Ps. 90.17)—and the importance of failure, suffering, and doubt in this work.