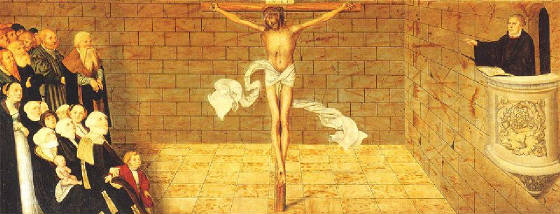

Lucas Cranach the Elder, The Wittenberg Altarpiece, 1547, Wittenberg, Germany

Modern and contemporary painting is the heart of my theology of culture. It is not the kind of cultural practice, however, that receives any positive attention from evangelical cultural theologians and critics, for whom art is irrelevant at best and harmful at worst. But painting is much more than meets the eye, as both the tradition of icon painting within the church and the history of modern art outside the church testify. But a theology of culture that cannot offer a positive account of the arts in practice is ultimately deaf to the diverse and unexpected sounds of grace in the world.

While finishing my doctoral dissertation and teaching modern art at a state university in the mid-1990s, I read Francis Schaeffer’s Art and the Bible and H.R. Rookmaaker’s Modern Art and the Death of a Culture, and I was shocked. Their conclusions about modern art bore no resemblance to the work I had devoted years of my life to understanding from within the history and development of modern art.

In response to Schaeffer and Rookmaaker, I began to develop a theological account for my interest in modern and contemporary art, which didn’t begin in the seminar room but where I live my professional a life as an art critic and curator: face to face with a work of art in an art museum, gallery, or studio. My goal was not to develop a “theology of the arts” that gets “applied” like a cookie-cutter to particular works of art or hovers abstractly in the ether, but to give a theological account for my interest in and love for particular artifacts of an especially despised and misunderstood cultural practice, which, as an evangelical, I had been called to serve. One of the results was God in the Gallery (Baker Academic, 2008), in which I moved outside the operative Reformed worldview framework, which I found too limiting, toward the Catholic and Eastern Orthodox traditions of the faith, to bring a more robust aesthetic, sacramental, and liturgical mindfulness to modern and contemporary art.

The outlier in my aesthetic evangelical resourcement was Luther, whom I had simply lumped into the Protestant tradition as a “pre-Calvinist” and a “post-Catholic,” shaped as I was by the biases of Catholic and Reformed interpreters, and art historians like Joseph Leo Koerner, who blamed the Reformer for a privatized, relativized, and disenchanted Protestant faith. But things changed when my family and I became members of a confessional Lutheran Church (LCMS) in 2004, and I discovered through the weekly practice of the preached Word and Sacrament, that Philip Cary is right: Luther is not quite Protestant. And for the sake of enriching evangelical cultural thought, that is a very good thing, as even Reformed historian Mark Noll observed in his classic essay, “The Lutheran Difference,” published in 1992 in First Things. But, unfortunately, as Kevin DeYoung admitted last summer, Luther and the Lutheran tradition remain virtually unknown to conference-circuit evangelicalism.

Although I practiced the Christian faith in the Lutheran tradition for almost eight years, it was not until I encountered Luther while a staff member of a Presbyterian church, and thus liberated from a confessional tradition that had domesticated his thought, and interpreted through sensitive readers like the Hamann scholar Oswald Bayer, Steve Paulson, Gerhard Ebeling, and Gerhard Forde, that he came alive for me, presenting to me a Luther I never knew. And a Luther evangelicalism desperately needs.

What I discovered is a Luther whose thought offers fertile ground for a desperately needed re-evaluation of evangelical approaches to art and culture, from his understanding of the distinctions between the letter and the spirit; law and gospel; theology of the cross and theology of glory; the kingdom of God and the kingdom of this world; the human being as simultaneously sinner and saint; God hidden and revealed; and nature and grace. In addition, in his revolutionary understanding of vocation, the radically unfree will, and emphasis on the sacramental nature of the preached Word, Luther opens up space to think freely and creatively about modern art, without expectations for what art should look like. For Luther, it is not what we see, but what we hear from paintings, as we live and feel the pressure of life and the strained relationships with our neighbor. That is how we are confronted by paintings, not in the seminar room but in the trenches.

And so I find Luther a welcome and helpful companion on visits to art museums and art galleries, when I am confronted by work that looks different, frustrating my expectations and distracting me by its strangeness. Luther is teaching me to wait in faith, and listen, with love.