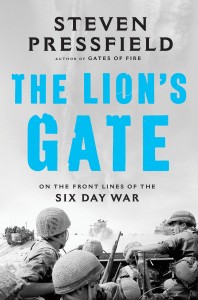

In conjunction with my review of Steven Pressfield’s The Lion’s Gate, I had the opportunity to do an e-mail interview with Pressfield himself.

In conjunction with my review of Steven Pressfield’s The Lion’s Gate, I had the opportunity to do an e-mail interview with Pressfield himself.

Woof: You’re clearly a lover of history. How did history as a subject first grab you? In my case, I’d always been a science fiction reader, and one day it occurred to me that historical novels were (in a way) just low-tech science fiction: history had strange and exotic locales, people with unusual ways, and so on. Reading novels led me to reading actual history. How did it work for you? Did it come out of your time in the Marines?

SP: After my first book, The Legend of Bagger Vance, I had no idea what to do next. I had always been an enthusiastic reader of stuff about ancient Greece. I would read Herodotus and Thucydides just for fun. Suddenly I thought, Why not write about the battle of Thermopylae! No one can spell it, no one can pronounce it, no one’s ever heard of it. Perfect! So I started on Gates of Fire. Somehow that got me going on history.

Woof: Are you primarily interested in military history? Or are you interested in history in general?

SP: When a novelist or screenwriter is looking for a subject, the element he’s seeking is conflict. Conflict makes drama. Conflict produces great characters and memorable scenes. So war is a natural topic. Ask Shakespeare, Tolstoy, Hemingway. But beyond conflict and characters, a writer is looking for a THEME. A story that’s about something. And what could be about something more than a war? From either side in a conflict, there’s a protagonist and an antagonist; there’s an issue (or more than one) that’s being fought over. The last element in drama is high stakes. War, of course, is life and death—survival, not only for the story’s characters, but often for the society itself. That’s why I’m drawn to stories that are built around wars, even if they’re not technically “war stories.”

Woof: You’ve written a number of books about the ancient Greeks, one about World War II, and now one about the Six-Day War. Are there other periods in history that have caught your fancy? Are we likely to see anything about China, the Silk Road, or the Raj?

SP: That’s a question I’m debating a lot within my own heart these days. I’m not sure where the Muse will take me next. Now that you mention it, Will, the Silk Road sounds pretty interesting …

Woof: What is your writing process like? Clearly you have do a great deal of research for each book; how do you organize your notes? Do you outline your books in detail before you start to write, or, having gotten the research done, do you simply start writing with a general notion of where you are going?

SP: My best answer is to read my books The War of Art and Turning Pro. I go into excruciating detail in both of them.

Woof: In addition to your historical novels, you’ve written one near-future thriller, The Profession; how do you find that writing the one kind of book differs from writing the other?

SP: A contemporary or near-future book is much harder because you can’t fake the facts. There are people alive who know much more than you do about the subject. You have to really have your research together—and of course no one can know everything about a topic. The great thing about writing about the ancient Spartans or Athenians is that so much knowledge is no longer extant that no one, except maybe a Cambridge or Oxford don, can call you out and prove you wrong.

In Tides of War, I wrote a long, long descriptive scene about the Athenian war fleet pulling out of Athens’ port of Piraeus, bound for Sicily. There were something like 200 ships and I named them all and told where each one was, in which squadron, etc. I made the whole thing up, every name of every ship. The great part is that, even though the reader may realize that the writer is crafting the entire scene from his imagination (because no one has the actual Order of Sail from ancient Athens), he or she can still enjoy it, just like you’d enjoy a scene in a pure fantasy tale like Game of Thrones because he or she knows there was a moment like this, and there were ships doing this—and why shouldn’t we get the fun of experiencing it in imagination even if the ancient Admiralty documents from Athens didn’t happen to survive twenty-four centuries into the present?

Woof: I first saw your name in a review of your book The War of Art; and later a friend told me that you wrote the best military historical novels he’d read. I was surprised to discover that the two Steven Pressfields were the same person. How did you come to write a book about art and creativity?

SP: Every artist has to face his own demons and evolve his own method of working. Twyla Tharp, the dancer and choreographer, wrote The Creative Habit, which was great and which evolved directly out of her own unique experience in the studio and onstage. Stephen King did the same with On Writing.

The War of Art and Turning Pro are my personal, idiosyncratic version of what the creative process is like for me, what demons I face and how I deal with them.

Woof: My eldest son is currently fascinated by World War II history. He’s read four of Churchill’s books on the war, and is currently reading two books, one on submarines in World War II, and Georg von Trapp’s memoirs of being an Austrian U-Boat captain in World War I. I’ve pointed him at The Lion’s Gate and Killing Rommel; are there other books on that time period that you’d particularly recommend?

SP: Too many to tell, but here are a few (some pretty obscure): The Forgotten Soldier by Guy Sajer, Lost Victories by Gen. Erich von Manstein, Brazen Chariots by Maj. Robert Crisp, and Alan Moorehead’s The Desert War; also With the Old Breed by E.B. Sledge. So many more. I love memoirs, particularly obscure ones because the writer is usually a regular guy just telling what happened to him and to his friends. What these tales lack in artfulness they make up for in passion and authenticity. For a writer of fiction, they are solid gold. I have stolen so much from memoirs it’s ridiculous.

Woof: I’ve read a fair number of books on military history, but there were graphic details in the first person accounts in The Lion’s Gate that took me by surprise. I first encountered a tank “brewing up” in George MacDonald Fraser’s Quartered Safe Out Here, but your description of the injuries of the soldiers caught in burning tanks and halftracks were new to me. (And I won’t dwell on them here.) Were you similarly taken by these first person accounts? Were there aspects of front-line warfare in these accounts that were new to you?

SP: What was new to me was the Israeli doctrine of warfare, as practiced not just on the strategic level by the generals but on the tactical level by sergeants and privates, and which has arisen directly out of the geographic realities of Israel (the short distances from the enemies’ borders, the lack of natural defensive barriers like rivers or mountain ranges, the fact of being outnumbered by so many millions) and by the history of the Jewish people in conflict over millennia, against foes from the Egyptians and Babylonians to the Romans, to the Nazis and now to the Arabs, in that the wars of Israel are inevitably wars of survival, with their enemies vowing to “wipe them off the map” or “drive them into the sea” and refusing even to acknowledge Israel’s right to exist. So that concepts like En Brera (“No alternative”), Dvekut byMesima (“Adherence to the mission”) and many others that are unique to Israel evolved naturally and inevitably.

The other aspect that impressed me deeply is that the IDF is a reservist army. Virtually everyone (there were only three regular-army brigades prior to the outbreak of the Six Day War) has to be called up from their civilian jobs. The democratic ideal of the citizen-soldier is absolutely the reality in Israel, as opposed to the professional army or the “all-volunteer” services.

Woof: In the acknowledgements for The Lion’s Gate, you say, “Through Danny I began to see that Israeli pilots and tankers and paratroopers are not simply Americans who happen to speak Hebrew.” That was a surprise to me as well. Similarly, I tend to think of being Jewish as being cognate with Judaism (although I do know better), and I was surprised at the wide range of religious belief and practice among the Israelis, from the first settlers to the young men and women born on Israeli soil. Of the things you discovered in your research for The Lion’s Gate, what surprised you most?

SP: There’s a phrase you hear in Israel: “We’re not Jews, we’re Israelis.” What that means is that the stereotype we’re familiar with here in the States of the Diaspora Jew, i.e. Jews in America or Europe or Russia, etc. does not fit at all with the reality of the homegrown “sabras” of Israel. There’s no Jerry Seinfeld or Woody Allen-type humor, no self-mockery or self-denigration, and no sense of “assimilation” as one finds in countries other than Israel. This was an eye-opener to a U.S. Jew like me.

Woof: Do you have a project in hand at the moment? And if so, what can you tell us about it?

SP: I’m superstitious, Will. I keep mum while I’m working on something. (I was expecting that…—Ed.)

Woof: And finally…what should I have asked you, that I didn’t?

SP: For anyone who wants to know more about the research and writing process for The Lion’s Gate, I’m doing a series of blog posts called “The Book I’ve Been Avoiding Writing” on my blog, www.stevenpressfield.com. They’ve been running for a couple of weeks now, every Monday and Friday, and they’ll keep running all through June. They’re not bad!

Woof: Thanks very much!

Steven Pressfield also has a series of videos on YouTube about the writing of The Lion’s Gate; you can find them here.