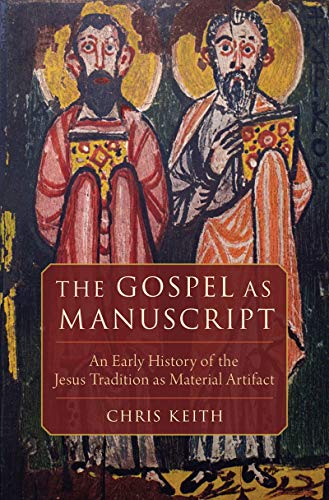

The Gospel as Manuscript (Oxford University Press, 2020)

We read the Gospels on our computers, phones, and in print, and we often take for granted that the story of Jesus was written down. We assume if something was important, it was inevitable that it became recorded in literature. Chris Keith, in his new book The Gospel as Manuscript, pauses to consider this event, the “textualization” of the Jesus tradition, as an important occasion in the lives of the early Christians. Here is his thesis in his own words:

[A]mong a variety of other factors, the competitive textualization of the Jesus tradition and the public reading of the Jesus tradition demonstrate that the reception of the Jesus tradition that unfolded in the first three centuries of the Common Era would not have happened in the precise way that it did without manuscripts (9).

It is true, Keith admits, that ancients valued in-person and oral communication; but this did not mean they saw textualization as bad per se. In fact, there was a key advantage to the book—allowing the message to have an afterlife, as it were: “The textualization of tradition creates the possibility of limitless reception contexts, allowing the tradition to be carried through time and space” (34). Using Mark as a key case study (as the Gospel manuscript), Keith shows how the first century “Neronian pogroms, destruction of the temple, and death of the first generation of apostles were all Traditionsbrüche [crisis events jeopardizing cultural memory] that could have called forth a textualized Gospel in order to stabilize the tradition into cultural memory” (95).

Not only did this writing down of the Jesus tradition stabilize the Jesus tradition to pass on the gospel story for the early Christians, but there also developed a whole reading culture around the use of holy texts, just as Jews did with Scripture in the synagogues. Keith writes, “what Christians did with manuscripts of the Gospels was an articulation of early Christian identity separately from, though ultimately in conjunction with, the narrative content of those manuscripts” (230). And later: “The Gospel book, and what one did with it, became a physical space on which Christian standing with the rest of the world was negotiated” (235).

The Gospel as Manuscript is a wide-ranging academic study of the textualization of the Jesus tradition, what it meant for the early Christians, how it developed into a gospel-writing culture, and what is says about early Christian identity. It is a very high-level academic study, with lots of technical language I had to “look up,” but I believe the patient reader will find much insight in these pages. As Keith readily admits, you can see the influence in this book of three of Keith’s mentors: Tom Thatcher, Helen Bond, and Larry Hurtado. I could indeed see the perspectives and interests of each of these woven into this book, which enriched it as a kind of interdisciplinary study. Congratulations to Chris Keith on this excellent contribution to scholarship on the Gospels and early Christianity.