Contemporary philosophical movements are not known for connecting on a practical level with Catholics.

Catholics tend to run like hell from them.

It’s as if they’ve been trained to think, “Just look at what contemporary philosophy has done to the Mainline!”

I’ve previously discussed here how things are different with phenomenology. This originally Eastern European (German, Polish, Czech, Austrian) revolution in thinking had a large Catholic following from the start. What’s more, it proved to be the gateway-thought for outstanding early 20th century converts such as Scheler, von Hildebrand, and Edith Stein.

Not bad, right?

The crisis-model of contemporary Catholicism has always bugged me to no end. My preoccupation with felling that old tree started long-ago with posts about Catholics (and other Christians) who write the highest quality poetry and novels right here and now. And you know what? You’d be hard pressed to find a time when there’s been mo’ better theologically-inflected literature. You live in a religious-literary Golden Age and you probably don’t even know it. I bet you even hanker for the O’Connor’s or Waughs of times past.

But when you look at contemporary phenomenology–what’s sometimes called Continental Thought to distinguish it from the sophisticated crossword puzzle anguish that is analytical philosophy (puts the anal in philosophy)–then there’s reason to triumphantly march out into the streets with your Catholic trumpets and zithers.

It’s especially the case with the French wing of phenomenology that features many thinkers of the caliber of Jean-Luc Marion (Derrida’s former student and generally acknowledged as one of the greatest living philosophers). The homeland of militantly anti-religious secular republicanism (ugh!) is utterly overwhelmed with debates about religion that are dominated by Catholic phenomenologists, but all that time you’ve been wailing against the secularism of the academe. Get over it!

In fact, they’ve come to call this moment in French philosophy the “Theological Turn in Phenomenology.” It’s really something to behold and celebrate. One wonders how this revival will spill itself out into the public life of France.

Michael Gubser’s The Far Reaches: Phenomenology, Ethics, and Social Renewal in Central Europe tells the forgotten history of how phenomenology has frequently oriented itself toward social renewal. In fact, it has served as the foundation for the most successful peaceful dissident movements of our time: Solidarity and Charter 77.

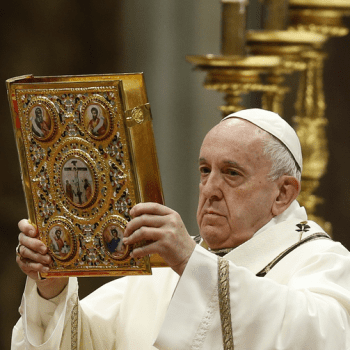

For example, in the chapters on Roman Ingarden, Karol Wojtyla, and Jozef Tischner Gubser reminds us:

“Solidarity, we should recall, was a Wojtylian concept [in The Acting Person] with Catholic and phenomenological roots before it became a trade union name; its papal invocation facilitated the translation of an obscure technical term with a long history into a mobilizing slogan with worldwide appeal.”

Phenomenology is often decried for being subjectivist because of its emphasis upon the intentionality of consciousness. While in some cases this did lead some phenomenlogists into the blind-alley of solipsism, for the most part phenomenology has developed robust accounts of transcendence in the horizontal and vertical directions. On the horizontal plane phenomenologists have written some of the most profound accounts of communal life and, as we have seen, their efforts have spilled out of the classroom into the social and ecclesial scene. On the vertical plane, phenomenology has always emphasized the importance of a hierarchy of values and virtues in a way unparalleled in modern times.

Gubser thinks phenomenology deserves its place in the sun for being one of the most robust historical attempts to navigate through the dangers of both left and right:

“The disappearance of this tradition [phenomenology] has implications that extend beyond a proper understanding of Eastern Europe. Since the 1980’s, our social and political vision has narrowed considerably, with a righteous liberalism the only widely available social and political discourse. East European dissidents, selectively misunderstood, have been conscripted as agents of this liberal triumph. They would have shuddered at the role. Only by neglecting their urgent warnings against Western technocracy and economism could Patocka or Wojtyla be turned into a liberal vanguard. Their social and ethical views, as this book has argued, derived from an independent tradition of phenomenological social thought, one that offered a personalist and communitarian social vision distinct from both liberalism and totalitarianism.”

In fact, Gubser is convinced that, against the presumed victory of a metastasized liberalism, phenomenology’s Central European past has a wider future:

“The recovery of this tradition, with all its strengths and weaknesses, can enrich contemporary social debates that are starved for novel visions of collective purpose. The same might be said of today’s ethical discourse, which increasingly privatizes morality–in either individual or religious form–to the detriment of any collective sense of identity and responsibility. In this denuded landscape, the renewal of a worldly phenomenology retrieves a valuable heritage that few know outside of Central Europe. It is high time for phenomenology to take its place among the leading social and ethical philosophies of the 20th century.”