Maundy Thursday usually has people twittering about whose carefully cultivated stinky feet will get washed and what canons might or might not get violated. This is all well and good, but as we gear up for Good Friday, we should start honing in on the absurd act of gratuitously inflicting violence on a God who graciously, even foolishly, empties himself out.

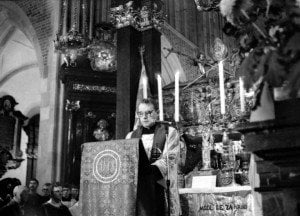

You might not be aware of this, but thinking, reacting, and rectifying the act of needlessly inflicted violence upon others was the cornerstone of the Solidarity movement in Poland. Fr. Jozef Tischner, a scholar of Husserl and phenomenology, became the unlikely chaplain of the workers’ movement–perhaps the single historical instance of the proletariat rising up against the bourgeoisie and ultimately winning non-violently.

I’ve been reading his reflections, The Spirit of Solidarity, which he wrote right in the middle of the movement’s organization, as an attempt to describe its thrust. He asks some pointed questions in this little book, questions that could have issued from both some kind of Polish theology of liberation and a traditional reflection on Holy Week (as if those two are mutually exclusive!):

“With whom therefore is our solidarity? It is, above all, with those who have been wounded by other people, with those who suffer pain that could be avoided–accidental, needless pain. This does not preclude solidarity with others, with all who suffer. However, the solidarity with those who suffer at the hands of others is particularly vital, strong, and spontaneous.

Does this touch politics? Yes, indeed; but only when the politics is corrupt. When politics is good, it is permeated of itself with the spirit of solidarity. Is it not the aim of politics to organize the arena of human life in such a way that one person does not inflict injury on another?”

He further explains the spirit of Solidarity in a way that ties it further to recognizing and responding to the senseless (from at least the human point of view) torture of Good Friday:

“This old but also very new word solidarity, what does it mean? To what does it call us? What memories does it bring back? To explicate more precisely its meaning, perhaps it is necessary to reach into the gospel and seek the origin of the word there. Christ explains its meaning: ‘Carry one another’s burden and in this way fulfill God’s law’ (paraphrase of Paul in Gal. 6:2). It means to carry the burden of another person. No one is an island all alone. We are bound to each other even if we do not know it. The landscape binds us, flesh and blood bind us, work and speech bind us. However, we are not always conscious of these bonds. When solidarity is born, this consciousness is awakened, and then speech and word appear–and at this point something that was hidden becomes manifest.”

This makes me wonder whether it is more important to pick up someone else’s cross rather than your own. Or, alternatively, perhaps is it not the case that there isn’t really much of a distinction between these two crosses?

By the way, it seems the pope was channeling solidarity-consciousness during Maundy Thursday Mass today: