By Alan Noble

The following is an exclusive feature that has been shared with you but is otherwise available only in Issue #20 of the Christ and Pop Culture Magazine.

For more features like this, download our app for iPad and iPhone from Apple’s App Store.

After a one-week free trial, monthly and yearly subscriptions are available for $2.99 and $29.99 respectively. New issues are made available every other week. More information here.

I don’t remember when the dreams started, but I know that one of the earliest began with my parents casually telling me that there was a body buried in our backyard in an upside-down bathtub. They assured me that we had talked about the body before, the guy we killed, or they killed, I can’t remember. It wasn’t a big deal, they told me. I didn’t remember the murder or the coverup, but I felt the dread anyway, overwhelming panic and anxiety. Guilt enough for the whole family.

We are going to be caught. Maybe not immediately, but someday we will get caught and punished. I will get caught and punished for a horrific crime that I don’t even remember committing. Why can’t we just get caught already? Just find us out and judge us and punish us and let it be over with. Why won’t murder out? Any punishment is better than this.

And the worst part about it was that nobody else seemed to care about our impending judgement. Just me.

After dreams like this, it usually would take me a while to calm down and convince myself that I really had no reason to feel guilt and dread. I hadn’t murdered anyone and neither had my parents. It was just a dream. But still, the specter of the dream might haunt me the entire day, this nagging feeling that I had done something terribly wrong and I could never make amends.

After dreams like this, it usually would take me a while to calm down and convince myself that I really had no reason to feel guilt and dread. I hadn’t murdered anyone and neither had my parents. It was just a dream. But still, the specter of the dream might haunt me the entire day, this nagging feeling that I had done something terribly wrong and I could never make amends.

And then the dream would repeat. These dreams always started in medias res, after the fact of the murder or crime, leaving me struggling to face judgement. In one dream my friends hit and killed some guy with their car. They all had no moral compunctions about fleeing the scene and leaving the dead man, but I sure as hell (an appropriate term here) did.

I’m not sure how many times I’ve had this dream about committing (or knowing that someone I loved committed) some heinous crime in the past and living with the constant sense of dread and guilt, but I do know that this anxiety has plagued my faith; that same feeling of dread has been known to drive me to lengthy bouts of obsessive thoughts: did I sin here? Did I act unlovingly to that person? Do I owe her restitution?

Sometimes I would even wake from these dreams and wonder if they were messages about some secret sin, warnings from my subconscious or the Holy Spirit that I was guilty and needed to confess and turn myself in. It took me too long to recognize that these dreams weren’t inspired by particular unrepentant sins, but by a deep and obsessive fear that there always was another sin back there, somewhere, in my past that I hadn’t asked forgiveness for, or apologized for, or paid restitution for–this fear that no matter what I did, no matter how cautious I was, I had probably done something wrong some moment in my life that had led to a series of terrible consequences, and there really was no way to know what or how or to repay it: It was the unbearable weight of being in the world.

* * *

We didn’t have cable, couldn’t afford it and didn’t want the corrupting influence anyway. Instead, we had tapes of a few shows made by Focus on the Family; some of my favorite tapes were from the McGee and Me series. The show’s premise was the perfect blend of archetypal school-drama and fantasy. Nicholas and his family move to a new town where he has to learn to fit in–navigating new friends, girls, and bullies. Guiding him through this time is his animated imaginary friend, McGee, a character Nicholas draws and talks to.

We didn’t have cable, couldn’t afford it and didn’t want the corrupting influence anyway. Instead, we had tapes of a few shows made by Focus on the Family; some of my favorite tapes were from the McGee and Me series. The show’s premise was the perfect blend of archetypal school-drama and fantasy. Nicholas and his family move to a new town where he has to learn to fit in–navigating new friends, girls, and bullies. Guiding him through this time is his animated imaginary friend, McGee, a character Nicholas draws and talks to.

Like all school or childhood dramas, the plots tended to revolve around ethical problems and the lessons learned from them, but as a Focus on the Family production, these moral lessons were about “biblical values.” You can imagine how attractive this premise was for Christian parents in the late 80s and early 90s. The show’s productions values were high. The plots were interesting and relevant, dealing with issues like skateboarding, horror movies, and lying to look cool. All of this without the sexual innuendo and language of secular TV. Instead, viewers were taught strong biblical values. Like most kids, especially kids without cable, I watched our tapes over and over, drilling these “biblical values” into my imagination.

But the only value that stuck with me was the terrifying, inestimable consequences of living.

* * *

The pilot episode of McGee and Me haunted me the most. “The Big Lie” tells the story of Nicholas’s first days at his new school. With McGee’s encouragement, Nicholas shows off to a neighbor named Louis by looking into the window of a notorious house—a house occupied by a “crazy old Indian” who eats stray animals, according to local legend. While peering in, Nick accidentally falls through the basement door into a dark basement filled with animals in cages. As he races out of the basement and through the house, Nick passes the “old Indian,” who is holding a rabbit, and runs home.

When Nick sees Louis the next day, Louis asks for all the details: “Was he big?” “Like a monster?” “Were there any animals?” “Did you see him eating any?” Nick repeatedly tries to tell the truth—that he didn’t see anything—but Louis keeps interrupting him, putting words in his mouth and exaggerating his story. Finally, Louis asks if the old man was eating the rabbit in his hands and Nick replies “Yeah, I guess. Whatever was left of it.” And thus the “The Big Lie” begins to work its evil.

Louis tells everyone at school and Nick gets the recognition and fame he wants. But immediately he’s plagued by guilt. The school bully Derek and his gang announce that they are going to go after the “crazy Indian,” too. Naturally, this only compounds Nick’s guilt. Because of his lie, the nice old Indian will be terrorized by a gang of kids. Nick goes home, haunted and depressed by his actions. So far, this could be an episode of Leave it to Beaver—a simple morality tale. But the narrative takes a dark turn with an animated parable about lying and guilt and the harm it causes.

* * *

The setting is a baseball field. McGee and his animated friends are playing ball and McGee hits a home run that goes out of the park, across the street, through the large glass window of a glass window store, and right into the head of the store owner, who gets knocked out. The kids hear sirens immediately. They panic and run, scrambling to escape before the cops arrive, but McGee can’t get out in time.

Police snipers surround the diamond, aiming their rifles at McGee, and a huge police officer with a bull horn demands that McGee surrender. Instead, McGee hands the bat to the only other person left on the field, an innocent little boy who is quickly arrested, dragged off, and thrown in a patty-wagon. The story ends with a shot of the small child clinging to the bars of the prison truck, looking out helplessly. Then they cut to McGee, who is stricken with the horror of what he has done. His silhouette fades as he hangs his head in shame.

Aside from the exaggerated animation style, this interlude is terrifying, especially as an allegory of our guilt before the Law. McGee breaks a window unintentionally because some city planner thought it was a good idea to put a baseball diamond across the street from a glass shop. The authorities swoop down with swift and absurdly disproportionate justice to drag a small boy off to prison. Since the story ends so abruptly there’s no trial and no chance for McGee to admit to his lie, so in the world of the parable McGee must spend eternity with the guilt of his crime. The injustice is suspended indefinitely with no hope for redemption.

There is a cruel absurdity to this moral world. We either break the law unintentionally and bring down extremely excessive judgement, or we break the law intentionally and escape judgement by shifting blame to someone else. This is a kind of animated version of Franz Kafka’s The Trial, whose main character, Joseph K. is arrested, tried, and executed without warning for a crime that the authorities never reveal to him. The novel is as terrifying as it is absurd. It’s not that K. wasn’t guilty before the law, it’s that he could never know the nature or extent of his crime or how he make restitution–the unbearable weight of being in the world.

* * *

A close friend of my parents is an alcoholic, an A.A. success story, actually, who hasn’t drank in probably twenty years. He told me once that when he did drink, he was a blackout drunk. There were huge gaps in his memory. He would go out drinking and the next thing he would remember he’d wake up at home. That’s why he won’t drink again, he told me. If he drinks, he has no way of knowing what terrible thing he might do and not remember the next morning. Could he even be sure that he hadn’t killed someone driving home drunk some night, twenty years ago? I should be in prison for the rest of my life, he told me. He wasn’t confessing a crime to me, but a lifetime of bad decisions that had consequences outside his control and purview.

A close friend of my parents is an alcoholic, an A.A. success story, actually, who hasn’t drank in probably twenty years. He told me once that when he did drink, he was a blackout drunk. There were huge gaps in his memory. He would go out drinking and the next thing he would remember he’d wake up at home. That’s why he won’t drink again, he told me. If he drinks, he has no way of knowing what terrible thing he might do and not remember the next morning. Could he even be sure that he hadn’t killed someone driving home drunk some night, twenty years ago? I should be in prison for the rest of my life, he told me. He wasn’t confessing a crime to me, but a lifetime of bad decisions that had consequences outside his control and purview.

He meant his words to be a warning against alcoholism, but I remember thinking that being a blackout drunk is just another way of describing the unbearable weight of being in the world. When you consider how many laws there are, moral and legal, and how many choices you make each day, and the billions of consequences of those choices, I wonder if there’s any of us who hasn’t unknowingly done some wrong that has led to someone’s death. We leave indelible marks on the world just by virtue of being alive. And some of those marks will be scars. Our existence is too weighty to keep from harming others, and there’s no way for us to know the extent of our harm or for us to undo it, as I learned from Focus on the Family’s McGee and Me.

* * *

When the cartoon interlude finishes, Nick’s dad comes to his son’s room to find out why he’s been so depressed. Rather than confide in his dad, Nick asks a hypothetical question: what if you said something wrong about someone and it could hurt them? His father offers ominous and prescient counsel, warning that the lie will hurt the person lied about and the liar, because, “Not only will the truth eventually find him out, but the very fact that lying is a sin, well, that sin starts to cut off his relationship, his friendship, with God.” Even worse, “If we lie and hurt another person, we hurt Jesus.” Nick’s dread only grows, and so he asks, “What do I do?” To which his father replies, “What do you think?”

When the cartoon interlude finishes, Nick’s dad comes to his son’s room to find out why he’s been so depressed. Rather than confide in his dad, Nick asks a hypothetical question: what if you said something wrong about someone and it could hurt them? His father offers ominous and prescient counsel, warning that the lie will hurt the person lied about and the liar, because, “Not only will the truth eventually find him out, but the very fact that lying is a sin, well, that sin starts to cut off his relationship, his friendship, with God.” Even worse, “If we lie and hurt another person, we hurt Jesus.” Nick’s dread only grows, and so he asks, “What do I do?” To which his father replies, “What do you think?”

The “biblical” lesson is that no matter how trivial a lie might be, once spoken, it begins a web of destruction and evil, consuming innocent people, cutting us off from God, and making an already-crucified Christ cry. Oh, wretched man that Nick is! Who or what will rescue him from this body of death? What can he do?

The only answer given: “What do you think?” That’s the most chilling part of this exchange. Nick is overwhelmed with guilt and fear, and his father’s response is to further explain the incomprehensible evil which he has committed, and then to tell him to just go figure it out.

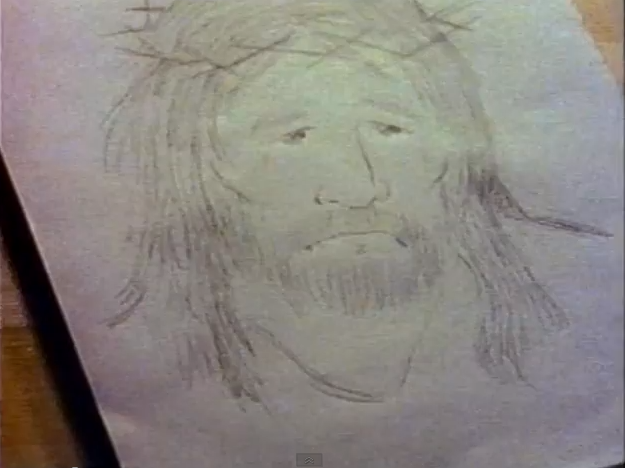

The following scene is a montage of Nick drawing the pained face of Jesus–wounded by Nick’s lie, presumably–juxtaposed with images of Derek and his gang as they go to the old man’s house and throw rocks through his windows, a clear allusion to the window breaking of the earlier cartoon. Over this scene a catchy 80s song plays, warning us that even if we “let it slip by” in “a moment’s hesitation,” our lie will have serious consequences. The montage ends with Derek’s gang running from the old house, into the mist, while Nick tosses and turns in his sleep, haunted by the pain he caused Christ and the “old Indian.”

* * *

The next day at school, Louis tells Nick that Derek and his gang are going to “put the finishing touches on” the old man. Nick panics, but McGee jumps out of his backpack and announces, “Time to right wrong, to return justice to its rightful [place]–” This is the answer to the question Nick had asked his dad the previous night: What do I do? You right wrong and return justice to its rightful place. And so Nick gathers his things and races to stop Derek.

By the time he arrives, the damage is already done. He finds the old Indian clutching his rabbit, bleeding and sad. While wind instruments play to remind us that he is, in fact, an Indian, the old man’s face fades into the image of Jesus that Nick drew the night before. Reminding us that this is the evil Nick’s lie has wrought upon God and men!

Except that this evil was actually wrought by Derek and his goons. Sure, Nicholas’s lie gave the bully an excuse to vandalize the old man’s house, and for that we might say he played a part in motivating the crime, but it was ultimately Derek’s choice and his actions. The imagery of the show would have us believe otherwise, however. The implication in this scene, as in the earlier cartoon interlude, is that we are responsible for all the catenations of our actions, of all our sins, of all our mistakes. The weight of being in the world is unbearable because the suffering we cause is our responsibility and yet out of our control.

* * *

But Nick learns to do the right thing. He makes up for his lie by cleaning up the mess Derek and his goons made and Louis tells him that he’s going to “catch it good from everybody” when he returns to school on Monday. Thus, any ill-gotten gains of popularity have been negated and he’s making restitution for his crime. And yet, and yet, an overwhelming sense of guilt and damnation cling to Nicholas’s soul:

I really can’t make up for what I did, McGee. I mean, I know God has forgiven me and stuff, but . . . I don’t know.”

Luckily for Nick, at that moment the old man brings him some lemon-aid and a slight smile, which finally lifts Nick’s spirits after spending nearly the entire episode in existential dread.

What’s remarkable about this show with its “biblical values” is that the Gospel is reduced to “I know God has forgiven me and stuff, but . . . I don’t know.” Is there a better articulation of our generation of evangelicals, taught so stridently about the need for the forgiveness of sins and yet so uncertain where our hope lies?

What Nicholas does know is that he “really can’t make up for what [he] did.” The weight of his fallen being-in-the-world is clearly evident, but God’s grace, His mercy? That’s not so clear. The Indian’s smile washes away Nick’s guilt. But what if he hadn’t smiled? Would Nick have gone on feeling the crushing guilt of his lie indefinitely?

We already have an answer to this in McGee’s animated parable: McGee had no hope for absolution from the evil of his lie–the innocent boy was falsely arrested and McGee is stuck with that guilt. Some sins have consequences beyond our control and those will haunt us for eternity. The world of McGee and Me is one in which the weight of being is utterly incalculable and irreconcilable. We are damned by existing at all, and the best we can hope for is to hurriedly make recompense, to clean up the destruction caused by our sin (intentional or not) through however many series of causes that destruction comes.

This theology of atonement through individual effort is attractive in its own way. We want sin to be containable. We want to draw a clear line of demarcation: this is my fault and this is not. And we desperately want to undo our sin, and I think that desire manifests in this episode’s message that we have to “right [our] wrongs.” But we can’t. We can never know how many people we’ve killed driving home drunk. If we could only manage our presence, our weightiness in the world, we’d be alright, but we can’t. However, there is one who loves us not because we can make him happy by never lying or because we have great relationship, untainted by sin, but because He died in our place.

As terrible as this show was for me as a kid, it did get the consequences of sin right. Sin is unimaginably destructive. We are all blackout drunks who’ve no way of knowing what great tragedy we have caused. We are inescapably weighty in our existence. But that’s only half of the story. Not even half.

As terrible as this show was for me as a kid, it did get the consequences of sin right. Sin is unimaginably destructive. We are all blackout drunks who’ve no way of knowing what great tragedy we have caused. We are inescapably weighty in our existence. But that’s only half of the story. Not even half.

Our being in the world is not impossibly heavy, but not because we move through life taking on our burdens by repaying our debts, making our being in the world light and airy and incorporeal by rising above life. No, our being in the world is good because of Christ’s prodigal grace–a grace which makes our being new in all its weightiness, a grace which is sovereign over all the catenations of our failures. His is a grace which forgives and redeems infinitely–the only burden-bearing which could possibly overcome our unbearable weight of being in the world.

* * *

Watching McGee and Me as a kid did not turn me into a legalist, but it did help shape my vision of what it meant to love God and seek forgiveness. It confirmed a deep fear I had and still wrestle with–the nightmare thought that I’ve killed someone, maybe a thousand someones, and I’m stuck between frantically trying to raise the dead and being condemned to death for their murders. But the show didn’t confirm the Gospel story, the message that I’ve been raised from the dead because Christ was condemned to death. And the only one who could ever know every catenation of our choices stands sovereign over all, and that same one looked upon me with love, and he undoes sin, whether it is real or imagined or dreamed.

Alan Noble, PhD is the Co-Founder and Managing Editor at CaPC and a part-time lecturer at Baylor University. He received his PhD in Contemporary American Literature from Baylor, writing on manifestations of transcendence in 20th Century American Lit. He and his family attend Redeemer Waco, a PCA church.

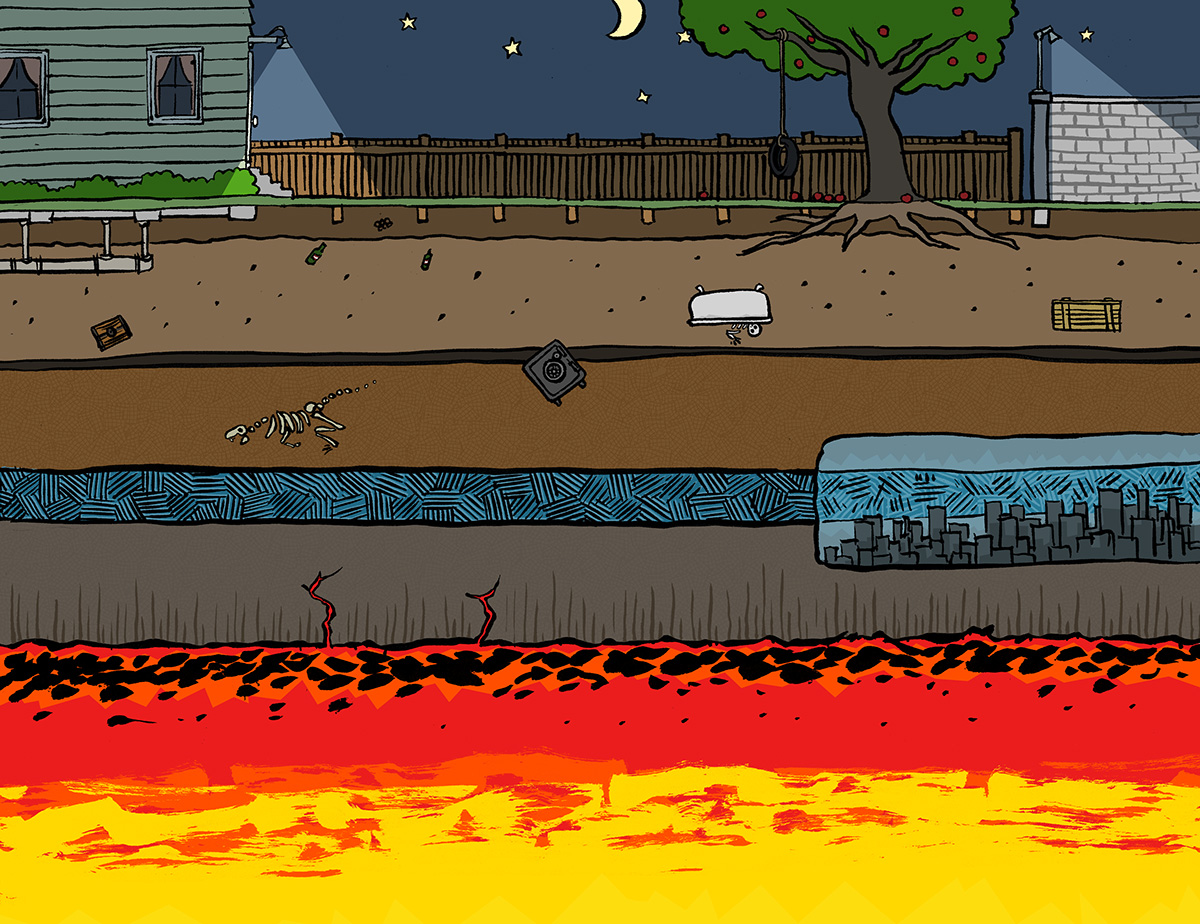

Illustration courtesy of Seth T. Hahne. Check out Seth’s graphic novel and comic review site, Good Ok Bad.