It’s been 12 years since “The Passion of the Christ” was released to a storm of controversy and a flood of money. Its detractors called it torture porn, and it was accused of anti-Semitism. But believers were moved and went to see it in droves; its $370 million gross was, at that time, the highest ever for an R-rated movie. Churches bused in audiences and hosted free screenings. People left in tears, many saying their lives were changed. This film still stands as one of the most controversial and most talked-about movies of all time.

It’s also been 12 years since I last saw Mel Gibson’s film. My viewings in theaters were two of the most visceral and unpleasant I’ve ever had. I sat there, tense and flinching at every blow delivered to Christ, wincing at the buckets of blood on the screen, and moved by the most graphic depiction of Jesus’ sacrifice that I’d seen. Even though we owned the DVD, I was never able to bring myself to rewatch it.

Eventually, I came to accept the common narrative about the film: that it was an overly brutal telling of the gospel story, filtered through Mel Gibson’s career-long obsession with violence and torture. It probably wasn’t very kind to the Jews, and it definitely didn’t have enough context to tell the story in a way that would encourage nonbelievers. We took its brutality and gore as a mark of maturity and seriousness, the same way that fanboys mistake Batman’s grim and gritty aesthetic as “adult.”

So I wasn’t exactly looking forward to revisiting Gibson’s film for my Lent series. But I knew that if I was looking at movies about Jesus, this was an important one. I slotted it for the end of the series, knowing that its fixation on Christ’s final hours probably made it best suited for the end of Holy Week.

Watching it again, I find that my relationship with this film continues to be complex. There are areas where its critics have a point, but it’s also a film with some deeply stirring moments. There’s definitely a lack of context; if you’re not someone who isn’t already moved by Christ’s story, you’re likely going to be turned off by Gibson’s portrayal of it. But for believers moving into a meditative mindset for Good Friday, there is undeniable power.

I don’t know that I’d call it a “good” movie, exactly. The seriousness that was so striking in 2004, particularly in the film’s first 30 minutes, now comes across as near-cartoonish bluster. Where most of the Jesus movies I’ve watched in the past month have excelled in presenting the people surrounding Christ as fleshed-out humans, Gibson creates disciples who are largely indistinguishable; aside from Peter’s denial and Judas’ betrayal, we don’t really know who’s who. Aside from Pilate, who gets a fairly sympathetic portrayal, every Roman guard is overly sadistic, not just beating Christ, but take intense pleasure from it.

The Jewish priests who turn Jesus over and call for his death are broad caricatures, depicted as scheming and evil, without any nuance. I understand that by this point a bloodthirstiness had set in, but this is where context would have helped; Christ’s death hinged so much on the fact that his words threatened the religious and political powers of that day. Without an understanding of that, Gibson’s film portrays an unruly mob assaulting and murdering a nice guy without much explanation.

Much of the heightened atmosphere may stem from the fact that the actors have to sell their film through performance, not dialogue. The film is famously told in Aramaic and Latin, and initially Gibson’s plan was to tell it without any subtitles. He, understandably, lost that battle, but the effect is that the amped-up performances give the film a heightened reality that comes off as overly aggressive. Add in Gibson’s penchant for slow motion and the cinematography’s deep blues and harsh oranges, and there are moments where “The Passion of the Christ” feels like a biblical epic told by Zack Snyder.

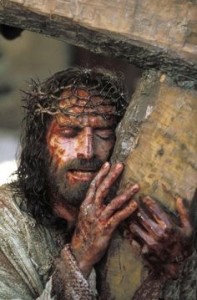

There’s also the issue of the film’s violence. This isn’t a film where a few nails and thorns draw trickles of blood. In Gibson’s film, whips rip chunks of flesh from Jesus’ side, pools of blood soak the pavement and Christ is beaten to a nearly unrecognizable pulp. There is a sense where this is necessary, but there’s also a sense where unrelenting brutality simply grows numbing after awhile. Nowhere is this more evident than in the scourging scene, which goes on for an agonizing 10 minutes and never flinches. Here, the violence builds until it no longer has an impact, turning the focus from Christ’s sacrifice to a cinematic endurance test.

Gibson’s always been a director with a weird affinity for torture — he turned the story of William Wallace into a blood-soaked tall tale and the story of the Mayans into a gory chase film. On one hand, he’s a director with a very sincere Catholic upbringing, and I don’t doubt his sincerity. On the other, when you consider the way he’s often fetishized torture, along with allegations of his own anti-Semitism and rage issues, it brings up questions of intent and whether the material is reverent or simply an excuse to vent his own frustrations.

Any way you slice it, this is an ugly and unpleasant film. That is, of course, by design. Christ’s trial and death were the darkest moments of human history, and they are events to be meditated on soberly. The brutality involved in Jesus’ sacrifice should not be taken lightly, glossed over or made palatable. Still, we often examine it in light of Christ’s perfect life and resurrection. And for those who come in to this movie without much understanding of the gospel, I can understand why “The Passion of the Christ” feels more like a snuff film than a holy experience.

And yet, is that lack of context a bad thing?

“The Passion of the Christ” was treated as an evangelism opportunity by many churches, who urged congregants to bring in unsaved friends to see Gibson’s story. But I don’t believe Gibson set out to make a faith-based film designed to convert people. Rather, I think he intended the movie to be a meditation on Christ’s final hours, the same way that churches stage passion plays or observe the stations of the cross. This is a film made for those have already been moved and changed by Christ’s story, and it serves as a chance to understand the extent of his sacrifice. In that way, I view the film in much the same way I view attending a Good Friday service or thinking on Christ’s death during communion.

What is Good Friday, after all, but a day when we briefly allow ourselves to narrow our focus on Christ’s story? We don’t preach from the Sermon on the Mount that day, nor do we discuss his miracles. While we know Resurrection Sunday is on the way, for a few hours we allow ourselves to put that out of our mind and spend the day focused on humanity’s darkest hours, when it appeared that sin had conquered.

Gibson’s film treats this as a horror movie, and I find that entirely appropriate. Unlike Scorsese’s “The Last Temptation of Christ,” which focused on Jesus’ internal struggle, “The Passion” externalizes it by heightening the supernatural aspects. Christ prays in Gethsemane and is taunted by an androgynous specter who twists the gospel and has worms crawling out of its nose. Later, as Christ is being scourged, the figure shows up again, carrying a deformed, demonic-looking infant in its arms, mocking the incarnation. Judas, meanwhile, is tortured by visions of demons, including a chilling moment involving some neighborhood children.

The horror movie tropes are effective and chilling, and hammer home the spiritual stakes of Christ’s final hours. The devil openly mocks Christ’s plans, hoping first to dissuade him and then to push him into despair. Jesus’ resoluteness in moving forward is seen as victory, foreshadowed in the film’s first scene when he smashes a serpent’s head under his foot. And while it’s easy to see Jesus as a weak figure here, there are notes in the film where Gibson stresses his calm and control. He tells Pilate that he has no power except what God gives, and when his mother comes to comfort him on the Via Dolorosa, he tells her, “See? I make all things new.” The film repeatedly emphasizes that no matter who sentenced Christ to the cross, it was a plan he had willingly planned to undertake from the beginning. I’m still moved by the scene where Christ clings to the wooden beams before setting out for Golgotha, and is asked “Why are you embracing your cross?” He embraced the cross because it was the plan all along.

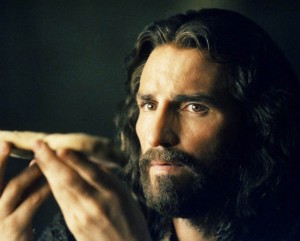

It’s here that I should mention how good Jim Caviezel is. He plays much of the film with one eye swelled shut, and apparently endured all manner of pain and discomfort while filming. It’s a strong performance, encapsulating peace and meekness while also depicting unimaginable pain. The flashbacks we get throughout the film allow Caviezel to show a warm, human side of Christ that provides a bit more context than I had remembered and allows him to be more sympathetic.

If the scourging scene is too much, Gibson finds a much better balance once Christ sets out for Calvary. He doesn’t shy away from the violence, but finds ways to make it beautiful and heartbreaking. He juxtaposes the stations of the cross with flashbacks to Christ’s life, and builds incredible resonance through them. When Mary watches Jesus fall, she imagines her son skinning his knee as a child and how she’d comfort him; it’s the film’s most heartbreaking moment. When Christ flashes back to the Last Supper, where he told his disciples that his body would be broken and his blood spilled for them, Gibson brings us back to the cross and shows just what that means.

There is a tough balance to telling the final hours of Christ’s life. If you show too much gore, you risk making the film numbing. But sanitize it and you wind up with a depiction of Christ’s death that is staid and analytical, devoid of the emotional power and visceral nature it must have. Gibson might go overboard with the violence during the scourging, but the flashbacks give us a slight respite as we head to the crucifixion. The film’s final hour paints those images beautifully, with Caleb Deschanel’s gorgeous cinematography recreating several Catholic depictions of the passion (although the guy getting his eyes pecked out by crows might be too much).

Despite my earlier hesitations, I found myself deeply moved. Yes, Gibson makes Christ’s body look like a piece of butchered meat by the end. But the Bible says that Christ was the Passover Lamb, the sacrifice that appeased God’s wrath and took away our sins. I look at the violence and think it might be too much, but I remember that Isaiah vividly describes a savior who was beaten beyond recognition. I take communion every month and often turn it into a quiet intellectual exercise; how often do I think about the reality that a man was brutally killed to save my soul?

I understand why many dislike this film, and I don’t fault them for that. It has its deep flaws — but then again, any attempts by finite creatures to understand an infinite God will have deep flaws. But on Good Friday, as my thoughts turn to the cross, I find that “The Passion of the Christ” might be one of the few movies to seriously contemplate the horror that transpired for three hours one Friday. I don’t know that this is a movie that I’ll revisit often, but I’m glad to have seen it this Holy week.

Other movies in my Lent 2016 series:

- The Gospel According to St. Matthew

- Jesus Christ Superstar

- Godspell

- The Young Messiah

- Easter Mysteries

If you like what you read, Like me on Facebook!