Photo Attribution: “Bound” By Quinn Dombrowski; Photo Source; CC 2.0

Photo Attribution: “Bound” By Quinn Dombrowski; Photo Source; CC 2.0

Modern evangelicalism contains numerous terms that summarize lengthy teachings in order to expedite scholarly work. These terms are incredibly important to our understanding of the framework that others operate under. Rather than developing an argument previously understood, writers are able to use such terms to get to the point of their own thesis.

In seeing these terms upon our study, we ought to implement the common, orthodox usage of them. However, much to the detriment of many laypeople, these terms are often ambiguously understood or used. In some cases, a person may misuse the term entirely, supplanting what they believe it to mean rather than the intended meaning.

In more recent years, we have seen scholars, such as Craig Bloomberg, redefine a term to nuance their own positions. In this specific example, Bloomberg has strayed from the common usage of the term “inerrancy” in order to supplant his own. With this in mind, it is helpful for us not only to understand the common definition given to inerrancy, but also Bloomberg’s position. A helpful place to start would be the Chicago Statement on Biblical Inerrancy

Once we have developed our understanding of the orthodox view on inerrancy, we can move forward to understanding those whom may use the same terms, but imply something entirely different.

- Why is this important?

- Why do we need to understand these documents and look to those in the past who have laid such foundations?

Simply put, Christendom has always been subjected to debate over vitally important doctrines. In this, one’s hermeneutic will inevitably “lift the skirt” and expose how they read the text. More plainly, their functional vocabulary will define how they approach and understand the scriptures.

A Dispensationalist will understand the term “covenant” much differently than one who holds to Covenant Theology; a Theonomist will differ greatly in their understanding of scripture’s usage of “Law” than your standard Reformed Covenantalist. A person who holds to Annihilationism will undoubtedly give a different definition to the terms “perish”, “consume”, and so forth.

The inherent issue resides within a presupposition that we define the same terms in the same manner. We might speak with one and both affirm the doctrine of biblical inerrancy, yet if his definition is different than our own – do we both believe the same thing? More importantly, do we arrive within the realm of orthodoxy when studying the scriptures?

If I speak to one more theologically liberal on inerrancy, his functional definition will differ greatly than my own; he might say that the fundamental truths of scripture are without error, but not the text itself. Thus, because of this, we are left to read scripture in a manner that treats the Creation account figuratively, denying the historicity of Adam and Eve as legitimate persons through whom we were sold into bondage to sin. While they may even affirm the sinfulness of man, they stray from orthodoxy and their theology will show this.

In any dialogue we have regarding the faith, we must define the terms. Why is this important? I firmly believe that we should not only know the error of poor teaching, but the route with which they took to arrive. This will further serve to make us aware to an author’s bias, the presuppositions brought with their stance, and help us to navigate well the hermeneutical road so that me may safeguard our own study of the scriptures.

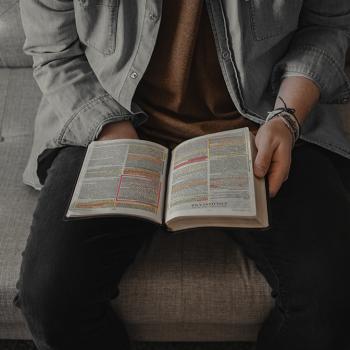

We have the Spirit to guide us in understanding these words, however, we function in an un-glorified state that is subject to deceit, misunderstanding, and willful rejection of the truth. If our task is to be transformed by the constant renewal of our minds, we ought to take utmost care and diligence in the methods we use to study divine writ. We must be vigilant in not only refusing heretical teaching; we must be vigilant in refusing a study methodology that logically leads one to accept such teaching.

We ought to know how to read our bibles in their proper genre, historical background, universal applicability, and even future applicability. We must know when to read scripture literally, and when to treat an allegorical text within that literary function. We need to know how to read wisdom literature, historical narrative, liturgical prose, and imperatival/polemical/instructional literature. If we neglect to do these things, we only serve to misunderstand our obligation as followers of Christ, and will continue to have a poor understanding of a marvelous God who revealed Himself artfully through human languages, histories, and cultures, yet fundamentally how the church is to function in response to the revealed truth of the Lord.

In summation, if we do not understand how to rightly divide the scriptures, we will only continue to navigate a path that goes contrary to the will of the Lord, and may find ourselves in a position of grievous error that we thought we would never land on. Perfect examples of this can be found all throughout the history of the church in the various councils held in order to affirm true orthodoxy, yet condemn heretical twists on non-negotiable theologies. We mustn’t neglect the foundation laid – yet we must also always be aware of scripture’s final, authoritative word over tradition, as the fully inspired word of God.