From the Logos Community Archives

In the spirit of the Easter season, and as an aid to believers; I recommend the excellent book by Frank Morison (Albert Henry Ross). Brother Mark edited November 2024

According to Amazon.com

This work has been selected by scholars as being culturally important and is part of the knowledge base of civilization as we know it.

This work is in the public domain in the United States of America, and possibly other nations. Within the United States, you may freely copy and distribute this work, as no entity (individual or corporate) has a copyright on the body of the work.

Wikipedia states

“Frank Morison (January 1, 1881 – 14 September 14, 1950), is best known today for writing the book Who Moved the Stone?, under the pseudonym Frank Morison. First published in 1930, the book analyses texts about the events related to the crucifixion and resurrection of Jesusof Nazareth. The book has been repeatedly reprinted (in 1944, 1955, 1958, 1962, 1977, 1981, 1983, 1987, 1996 and 2006). Ross was skeptical regarding the resurrection of Jesus, and set out to analyse the sources and to write a short paper entitled Jesus – the Last Phase to demonstrate the apparent myth. In compiling his notes, he came to be convinced of the truth of the resurrection, and set out his reasoning in the book Who moved the stone?. Many people have become Christian after reading the book, and some have used the work as a reference for more work on the subject.”

Here is a sample of a chapter of that book.

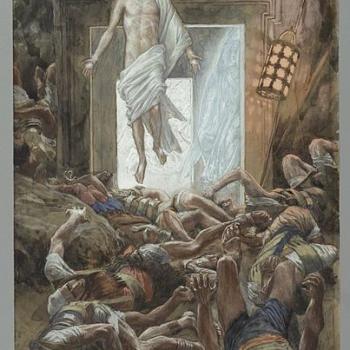

CHAPTER XIV—SOME REALITIES OF THAT FAR-OFF MORNING

What is the secret of this silent and impenetrable tomb? It is a question which presses insistently for an answer.

There are certain things about this story which impress me profoundly. They are not the kind of things which can lightly be set aside as of minor or only relative importance. They belong to the fundamental and bedrock

features of the problem. In the first place, whatever the physical or dogmatic consequences may be, I cannot and do not believe that the body of Jesus of Nazareth rested in Joseph’s garden during any part of that period

which is contemporary with the rise of Christianity.

If it could be shown that there was a single document of admittedly early date dealing with the crucifixion and burial of Jesus in which it was even remotely hinted that such was the case, I for one should attach to that hint

very considerable weight. It would at least introduce the same kind of uncertainty which exists concerning certain other aspects of the problem. It would provide a peg, however shaky and insecure, upon which to hang a

doubt. But the documents are adamant upon this fundamental feature of the Easter dawn.

Whether we turn to the two dependent Gospels, St. Matthew and St. Luke, to the comparatively unorthodox Gospel of Peter, to the Gospel of St. John, to the Emmaus document preserved by St. Luke, or to the admittedly

primitive Marcan fragment itself, we find the same consistent and unvarying witness to the disappearance of the body. If the situation had been the other way round; if we had been asked to believe something which

was denied by every solitary manuscript which has survived the centuries, how solid and unanswerable would that cumulative and absolutely unanimous denial appear! What play could be made by the dialectician with

the fact that not the smallest chink or loophole had been left for doubt.

Surely (it would be contended), the real truth must have blundered somewhere to the light. Yet in all the varied literature from that far-off time, written under different skies, by men of varying temperaments, possessed

by obviously divergent theories of the true course of those memorable events, there has come down to us no hint or suggestion that the facts about the grave were other than those substantially recorded in the Gospel

according to St. Mark. However disconcerting the fact may be, the literary verdict is unanimous and must at least be given its due weight by the impartial mind.

But there is something far more arresting and significant than even this unanimous literary witness, and I do not see how even the most confident of modern critics can view it steadily and consistently without experiencing a

feeling of profound disquiet and unrest. I mean the extraordinary silence of antiquity concerning the later history of the grave of Jesus. It is strange—this absolutely unbroken silence concerning a spot which must have been a very sacred place to thousands of people outside the circle of the Christian believers themselves. If the disciples were deceived in this matter, or if the intensity of their faith in the Appearances led them to ignore or to attach no importance to the condition of the grave, what of the preponderant mass of the Jewish public outside? Did no one regard with reverence the sepulchre which held the mortal remains of the greatest Teacher that Israel had seen since the prophetic days? Had Joseph of Arimathea and Nicodemus no counterpart among all the toiling multitudes who crowded round the boats on the shores of Galilee and filled Capernaum and Cana and Nazareth with tumultuous throngs? Surely for every man or woman who came under the magnetic influence of the disciples there must have been a hundred who had no illusions concerning the grave, but were filled with profound grief and sorrow by the untimely death of Christ.

Yet we can search in vain for any sign or hint or whisper that during those first four crucial years when the Christians were teaching their strange doctrine within the walls of Jerusalem there was a stream of pilgrims to that

silent grotto beyond the gate. We catch no echo of any controversy between the many who knew the real facts and the deluded few who taught and presumably believed otherwise. Why did the least believable of all the cults

of Christianity survive and leave no traces of the one rational and divergent form which, according to all reasonable expectation, ought to have overmastered it and triumphed in its stead?

Or take the same central problem from another and slightly different point of view. Let the reader sit down and in the quiet of his own study ponder one very simple but searching question. Why was it that Jerusalem

became the centre and focus of this mad unreason which in the coming years was to spread itself outwards to the uttermost limits of the Roman world? Why Jerusalem in preference to Capernaum, or even Nazareth

itself? There are a hundred reasons why so demonstrably fragile a myth as the belief in the physical resurrection of Jesus ought to have flourished in the congenial soil of Galilee and to have withered within the precincts of

the real grave.

Jerusalem was always hostile and unsympathetic to the genius of Christ; Galilee was His home. Those who loved Him best and must have mourned Him most came from that smiling province. No one seriously doubts that

within fourteen days of the Crucifixion Peter and Andrew and some others of the Apostolic band stood upon the shores of that inland sea and felt the call of their ancient and honourable trade. Granted that a vision came to one

of them and perhaps to all. But why did not this mystic church of believers spring into being and strike its deepest and most central roots in Galilee, the spiritual home of Jesus, a place impregnated with His personality and

teaching? Why did everybody who caught the infection of this spring madness gravitate to Jerusalem as steel to a magnet? Why should so irrational a doctrine flourish most readily and take its implacable stand in

the veritable presence and vicinity of that which it denied?

There is only one answer to all these questions which satisfies alike the unanimous literary witness and the collateral requirements of historical circumstance. It lies in the assumption that the story of the women’s visit to

the grave—as given in all its primitive and naked simplicity in the Marcan fragment—is the true story. It was told, not because it had any particular apologetic value—for as an apologetic it can be riddled with criticism—but

because things fell out that way. In other words, it was a fact of history.