In a previous post ‘Mysterious Lives of Christ’, I quoted from

LIFE OF CHRIST (1923) by Giovanni Papini

That book is in the public domain.

Here is another passage from this book that you can freely download, and copy, and reuse and do whatever you want with, without restriction as it is once again in the public domain. That is the joy of the public domain and there are lots of good Catholic books forgotten about for years that you can enjoy and be edified like this one.

The man of imagination sees everything as though it were new:

every great star, wheeling in the night, might lead you to the house hiding the Son of God;

every stable has a manger which, filled with dry hay and clean straw,might become a cradle;

every bare mountain top flaming with light in the golden mornings above the still somber valley,

might be Sinai or Mt. Tabor:

in the fires in the stubble, or in the charcoal kilns shining on the evening hills you can see the flame lighted by God to guide you in the desert;

and the column of smoke rising from the poor man’s hearth shows the road from afar to the returning laborer.

The ass who carries the shepherdess just come from her milking is the one ridden towards the tents of

Israel, or the one which went down towards Jerusalem for the feast of the Passover.

The dove cooing on the edge of the slate roof is the same that announced the end of the

great punishment to the Patriarch, or the same that descended on the waters of the Jordan.

For the poet every thing is of equal value and omnipresent, and all history is sacred history.

The man who is thought to be behind the times often is a man born too soon.

The setting sun is the same which at that very moment colors the early morning of a distant country.

Christianity is not a piece of antiquity now assimilated, in as far as it had anything good, by the wonderful and not-to-be-improved modern-consciousness;

but it is for very many something so new that it has not even yet begun. The world to-day seeks for peace rather than for liberty,

and the only certain peace is found under the yoke of Christ.

They say that Christ is the prophet of the weak, and on the contrary

He came to give strength to the languishing,

and to raise up those trodden under foot to be higher than kings.

They say that His is the religion of the sick and of the dying,

and yet He heals the sick and brings the sleep ing to life.

They say that He is against life, and yet He conquers death;

that He is the God of sadness, and yet He exhorts His followers to be joyful

and promises an everlasting banquet of joy to His friends.

They say that He introduced sadness and mortification into the world,

and on the contrary when He was alive He ate and drank,

and let His feet and hair be perfumed,

and detested hypocritical fasts, and the penitential mummeries of vanity.

Many have left Him because they never knew Him.

Not Secretive: A Poet

Jesus seems at first sight secretive.

He orders those affected by miracles to say to no man who has cured them;

He wishes prayers and charity to be done secretly;

when the disciples recognize that He is the Christ,

He charges them not to repeat it;

after the Transfiguration He bids the three keep silence,

and when He teaches He uses parables which all men are not capable of understanding.

On further thought, on really considering the matter, it is apparent that Jesus has nothing of the esoteric.

He has no secret doctrine to impart to a few acolytes.

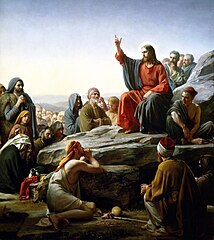

His words are public and open.

He always speaks in the public squares of cities, on the beaches of lakes, in the Synagogue,

in the midst of the people.

He forbids speaking of His miracles in order that He may not be confused with wizards and exorcists;

He commands to do good secretly in order to keep vainglory from destroying merit;

He does not wish the Twelve to proclaim Him the Christ before His entry into Jerusalem,

the public inauguration of His Messiahship;

and He speaks in parables to be better understood by the simple who listen more willingly to a story

than to a sermon, and remember a narration better than an argument.

Three of the Evangelists report a speech of Jesus, which seems to contradict this view.

“Unto you,” He is speaking to the disciples,

“it is given to know the mysteries of the Kingdom of God, but to others it is not given;

therefore I speak to them in parables that seeing they might not see,

and hearing they might not understand.”

But Jesus means only to say this, “You understand these mysteries,

but the many do not understand them, although they have ears and spirits like yours.

And to them that they may understand I speak in parables,—that is,

in a figurative language of facts because it is easier and more familiar.

” You teach children with fables and the simple with stories,

and “the many” have remained like the simple and the childish.

To overcome the slowness of their minds I use words adapted to their nature.

They are all fancy, and little intellect;

and the parables are an appeal to the imagination more than to the reasoning powers.

I do not employ them therefore to hide the truth,

but the better to reveal it to those who could not see it in a purely rational form.

For if then they do not understand, it is the fault of their obstinacy,

which often closes the eyes and ears of the soul.

Jesus had no mysteries to dissemble.

It was His wish that all, even the most humble and ignorant, should understand Him.

The parables were not made to hide His teaching from the profane, but to make it more explicit

and understandable to every one.

That sometimes even the intelligence of the Twelve is inferior to this task is a melancholy conclusion by no means unknown to Jesus.

The marvelous content of His message has cast into the shade His poetic originality, not less marvelous.

Jesus never wrote—once only He wrote on the sand, and the wind destroyed forever His handwriting

—but in the midst of a people of powerful imagination,

of the people who wrote the Psalter,

the story of Ruth,

the book of Job,

the Song of Songs,

He would have been one of the greatest poets of all times.

His victorious youthfulness of spirit,

the racy, popular language of the country where He grew up,

the books He had read,

few but among the richest of all poetry

—His loving communion with the life of the fields and of animals and above all

His divine and passionate yearning to give light to those who suffer in the dark,

to save those who are being lost forever,

to carry supreme happiness to the most unhappy

(because true poetry does not catch its fire from the light of the lantern

but at the light of the stars and of the sun,

is not found in the writings left behind by great-grandfathers,

but in love, in sorrow in the deeply moved soul);

these things combined made of Jesus a poet, an inventor of living and eternal images

with which he achieved a miracle on which the Evangelists make no comment,

—the miracle of communicating the highest truth by the means of stories so simple,

familiar, full of grace that after twenty centuries they shine with that unique youth which is eternity.

Some of these stories are only idyllic or epic restatements of revelations

which at other times He expounded in abstract words;

but there are some which express things never said in any other form in His teaching.

The parables are the imaginative comments on the Sermon on the Mount,

such as could be made only by a poet who merits the tide

of divine more truly than any other poet ever born.