If you happen to be neck-deep in the controversy over whether artificial birth control is ever morally permissible, you may be familiar with the argument that the Church has changed her teaching in the past – specifically in the matter of usury.

Basically, if you go back to older encyclicals, like Vix Pervenit, you find that usury is condemned in no equivocal terms as a grave sin. Charging interest of any kind has been categorically condemned by multiple Popes and several Church councils. There are well developed natural law arguments which show that charging interest is unnatural, essentially because it causes money, which is innately sterile, to reproduce itself.

Yet, after affirming that Vix Pervenit applied to whole Church in 1836, Rome slowly fell silent on the subject of usury. Eventually regulations were quietly passed allowing religious congregations and the Vatican’s own bank to levy interest charges. The teaching was never actually struck down on the books, but in practice it fell into abeyance.

Those who advocate for a change in the Church’s teaching on birth control see a potential parallel. They see Humanae Vitae as the Vix Pervenit of the 20th Century, and of course have noted with some relief that Amoris Laetitia mostly glosses over the birth control question entirely. They see this silence as similar to the Vatican’s silence on usury, and read into it a kind of sheepish, tacit admission that the former teaching was wrong.

I think there actually is a good parallel, and I do think it’s very likely that in the coming centuries the Vatican will allow the teaching on artificial birth control to slide into obscurity. But I also think that it’s problematic to see that as an admission that the teaching is wrong.

Let’s start with usury. Vix Pervenit was published in 1745 during the midst of a somewhat different Culture War than the one we are fighting now. Traditionally, in the Catholic world, usury was legally prohibited – for Christians. However, this posed a problem: a charitable individual might be willing to lend money without interest to a neighbour who was down and out, but nobody was going to lend vast sums of money to powerful Christian leaders unless they stood to make a substantial profit.

You couldn’t fund major international conflicts with a begging bowl, and taxation could only get you so far. So Catholic leaders invited wealthy Jewish investors into their kingdoms and provided them with various forms of legal protection so that they could take advantage of the loophole in the law that allowed Jews to loan money at interest. After all, it wasn’t a sin to be a victim of usury.

The uneasy relationship between Christian leadership and Jewish moneylenders allowed powerful Catholics to observe the letter of the law while still benefiting from the availability of large loans secured on interest. But Protestantism destabilized that arrangement. Protestant leaders had the ability to regulate money-lending however they liked. They didn’t have to get permission from Rome. After the Reformation, Christian money-lending slowly came to be tolerated more and more in Protestant countries – which enabled, to a large degree, the development of modern banking and capitalist economies.

This created a social situation where it became increasingly difficult to maintain the traditional prohibition. In modern economies money does not keep its value in the way that Aquinas suggested: it’s not a commodity of fixed value which you can exchange on a one-to-one basis with other commodities of fixed value. Instead, the value of money is constantly in flux and a lender who expects to receive nothing except for the face-value of his original loan will pretty much invariably be lending at a loss because of inflation.

Vix Pervenit did suggest a means of circumventing this problem by allowing for various types of “extrinsic titles.” This meant that you could charge a reasonable administrative fee for any loan, and then try to draw up a loan contract so that you would actually neither make money nor lose money on the loan itself. I imagine that accurately calculating extrinsic titles was probably about as easy, and reliable, as charting irregular cycles using sympto-thermal.

Needless to say, the “extrinsic titles” idea didn’t really solve the problem very effectively for the large majority of Catholic businessmen. There were wide-ranging disputes as to what, exactly, constituted a fair extrinsic title. Banks increasingly paid out a small amount of interest on any moneys deposited, so even someone who wasn’t actively lending might be receiving interest payments. The highly successful Protestant economies of the early industrial era allowed for interest to be charged, and it became more and more impractical for Catholics to participate in international commerce if they were trying to practice the teaching.

So the Church dropped it. Or rather, dropped the insistence that charging interest was a mortal sin.

But She has never reversed the teaching.

Indeed, if you look at modern encyclicals the subject of international loan forgiveness comes up again and again. The Church decries the large-scale effects of usury, especially in international markets, while tolerating the day-to-day participation of the faithful in an economy that is kind of inescapably usurious.

Why this toleration, though? Did the Church give in because of avarice? Did the hierarchy realize that they were wrong but don’t want to admit it? Did they cave to pressure from liberal Catholic businessmen – including, let’s face it, wealthy donors to the Church? What happened?

I’d like to suggest that maybe, although more sordid reasons almost certainly played a role, there’s a sound moral and theological reason for this toleration. Specifically: the need not to burden consciences.

It’s similar, in a lot of ways, to the approach that St. Paul took to the eating of meat sacrificed to idols in Corinth. The first Council of Jerusalem was clear that Gentile converts needed to avoid such meat, but the reality was that if you went to a Corinthian market you were going to be hard pressed to find a roast that hadn’t been consecrated to some problematic deity or other. So Paul advises a kind of “don’t ask, don’t tell” policy. Buy your meat. Say grace. Don’t scruple.

This alleviates the practical burdens on Corinthian converts, and prevents the pursuit of food purity from becoming a day-to-day struggle that will alienate people from the Gospel and impede the growth of the Church.

Similarly, the Church’s toleration of usury reflects a realization that the kulturkampf of the 19th Century was largely lost. Contemporary economic reality makes it unduly onerous to avoid interest payments altogether, and really the average person who gets a piddling interest payment on the money they deposited in their bank is getting a lot less than they would get if it were possible to fairly calculate all of the reasonable extrinsic titles that they would be entitled to.

So the focus now is on reforming the unjust international systems that make it functionally impossible for Catholics to avoid participation in usurious practices. It can be assumed that the average parishioner is not in a position to have a) full knowledge that they are actually benefiting from unjust interest payments, or b) real freedom to engage in economic life without risking the sin of usury. Therefore, although this remains grave matter it is, in practice, unlikely to be a mortal sin unless someone is involved in rapacious loan-sharking or other obviously immoral activity.

So how does this relate to the question of birth control? I think arguably there is a similarity. The realities of contemporary life have made it increasingly onerous for Catholics to practice the teaching. Because birth control has been almost universally accepted by secular society, social conditions have become increasingly hostile to large families and most people are not able to access the kind of community support and financial security that is necessary to responsibly care for an ever-growing brood.

Social conditions are also not especially conducive to chastity. Early exposure to pornography and the more or less ubiquitous undercurrent of sexual titillation that runs through advertising and popular culture poses a real obstacle for those who are attempting sexual self-mastery. Other factors, like the increasing isolation of individuals, the loss of functional face-to-face community, the pressures that modern society places on marriages and on parents, the devaluation of human life (especially “non-productive” human lives), and the lack of adequate cultural tools for encouraging affective maturity when it comes to sex, also present considerable difficulties.

Under these circumstances, I won’t be surprised if over the coming decades we see increased toleration for birth control from the Church. The focus is likely to shift, as it has with usury, towards fixing the societal ills that make it so difficult for people to welcome children into their lives.

This will not mean, however, that the teaching has changed, or that the objective evils involved in contraception will magically go away.

Usury is still evil. It still drives economic practices that put poor people in debt, and make it impossible for them to escape. It creates an international situation where entire nations are trapped in debt cycles that fuel starvation and strangle development. It drives massive social inequities and enables avarice on a terrifying scale. And it provides the capital necessary to fund and perpetuate international conflicts.

If contraception becomes tolerated on an individual level, the objective evils associated with it will also remain. The reduction of women to fungible sex-objects will continue apace. Social and economic life will continue to be structured in a way that penalizes motherhood. Families will continue to face pressure to “terminate” children who don’t meet ableist standards for personhood. Mothers will continue to overwhelmingly bear the burdens of “unwanted” pregnancy alone. Childbearing will continue to be seen as an irresponsible choice, a threat to planet. And a utilitarian view of the value of human life will continue to dominate Western culture.

If the Church continues to lose the Culture War against the sexual revolution, the only thing that is likely to change is the assumption that individual Catholics have substantive freedom to overcome these pressures. Without that freedom, contraception, like usury, remains grave matter but becomes increasingly unlikely to constitute mortal sin in individual cases.

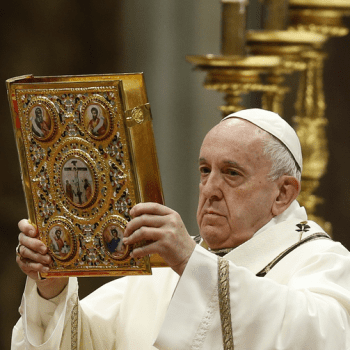

Image credit: pixabay

Stay in touch! Like Catholic Authenticity on Facebook: