Today is Martin Luther King, Jr. Day. Dr. King was born in 1929, and if he were alive today, he would be celebrating his ninety-second birthday. I am always shocked to remember that he was only thirty-nine years old when he was assassinated. His prophetic activism for peace and justice ended tragically early.

It is also important to remember that Dr. King did not accomplish anything on his own. And this year’s MLK Day also brings to mind other giants of the Civil Rights Movement from the Atlanta area who died this past year:

- The Rev. Joseph Lowery (1921-2020), often called the “Dean of the Civil Rights Movement,” died in March.

- Rep. John Lewis (1940-2020), who challenged us to carry on his legacy of getting into “good trouble,” died in July.

- The Rev. C. T. Vivian (1924-2020), who Dr. King once called “the greatest preacher to ever live,” died the same day in July as Rep. Lewis.

Along these lines, on this MLK weekend that finds us amidst significant societal upheaval, it seems like an auspicious time to do something that I’ve considered doing for many years—which is to reflect on the life and legacy of Dr. King (1929-1968) not in isolation, but in conversation with his compatriot and colleague in the struggle for human rights, Malcolm X (1925-1965).

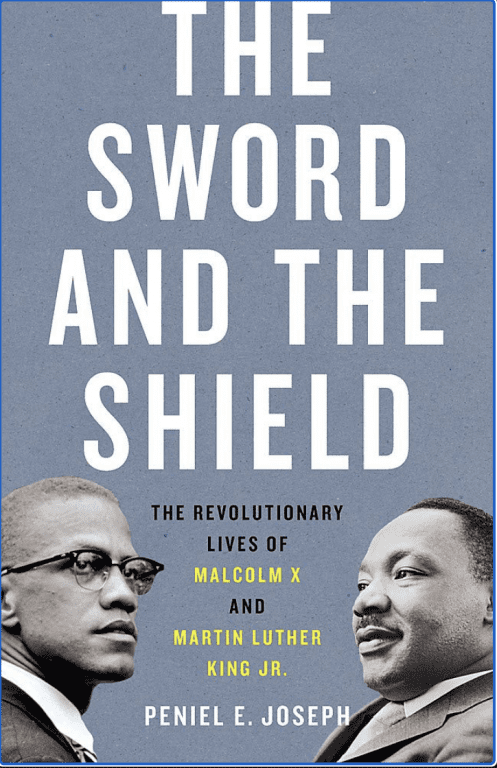

I first started thinking about juxtaposing these two figures in seminary, when I read Martin & Malcolm & America by the Black liberation theologian Dr. James Cone (1938–2018), a book first published thirty years ago in 1991. I was motivated to finally get back to this topic when I saw that Peniel Joseph, a history professor at the University of Texas at Austin, had published a new book titled The Sword and the Shield: The Revolutionary Lives of Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr.

I first started thinking about juxtaposing these two figures in seminary, when I read Martin & Malcolm & America by the Black liberation theologian Dr. James Cone (1938–2018), a book first published thirty years ago in 1991. I was motivated to finally get back to this topic when I saw that Peniel Joseph, a history professor at the University of Texas at Austin, had published a new book titled The Sword and the Shield: The Revolutionary Lives of Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr.

To start at the beginning, Malcolm and Martin were born a little more than four years apart, in 1925 and 1929 respectively, and assassinated a little more than three years apart. Both men were only thirty-nine years old when they died. And they really were colleagues in the struggle for black dignity, with the years of their public work overlapping—Malcolm X (1952 – 1965) and Dr. King (1955 – 1968). And as colleagues sometimes do, they had significant differences.

And although they were often depicted as foils for one another, that dichotomy misses how they also influenced one another, as well as that they ultimately came to share the same goal—what the Sixth Principle in my chosen tradition of Unitarian Universalism calls “The goal of world community with peace, liberty, and justice for all” (Joseph 13).

In particular, it is not always appreciated that Malcolm X made some of what Dr. King accomplished possible. Although Dr. King was quite radical, he often seemed comparatively moderate in contrast to Malcolm X (14). As historian Peniel Joseph has said, “King’s conciliatory image masked the beating heart of a political radical who believed in social democracy, privately railed against economic injustice, and viewed nonviolence as a muscular and coercive tactic with world-changing potential” (6). Likewise, too sharp a focus on Dr. King can obscure all the ways Malcolm X was also a “brilliant activist, organizer, and intellectual” (16).

Let me give you an example of this interweaving dynamic. If you read the entirety of Dr. King’s “I Have a Dream” speech from the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom—not just the famous ending—you’ll find some radical demands that are less well known. Notice, for instance, the subtext of reparations, as well as and the call to not slow-roll the movement to equality in this segment of King’s speech (160):

America has given the Negro people a bad check, a check which has come back marked insufficient funds. But we refuse to believe that the bank of justice is bankrupt. We refuse to believe that there are insufficient funds in the great vaults of opportunity of this nation. And so we’ve come to cash this check, a check that will give us upon demand the riches of freedom and the security of justice. We have also come to this hallowed spot to remind America of the fierce urgency of now. This is no time to engage in the luxury of cooling off or to take the tranquilizing drug of gradualism. Now is the time to make real the promises of democracy.

Taken by themselves, those are strong words, especially for 1963.

But if we zoom out, consider how much less strident King’s words sound compared to what Malcom X was saying more than a year earlier in May 1962: “What is looked upon as an American dream for white people has long been an American nightmare for black people” (Cone 89).

But it’s important not to stop with Malcolm’s comparatively strong radicality. We need to keep following the strand and notice one more important twist that is often left off this story. Let us fast-forward a few years, almost three years after Malcolm X’s assassination and a little more than three months before Dr. King’s assassination. In December 1967, Dr. King’s “Christmas Sermon for Peace” includes powerful words that show some of the ways that Dr. King’s and Malcolm X increasingly converged:

In 1963…in Washington, D.C.,…I tried to talk to the nation about a dream that I had had, and I must confess…that not long after talking about that dream I started seeing it turning into a nightmare…just a few weeks after I had talked about it. It was when four beautiful…Negro girls were murdered in a church in Birmingham, Alabama. I watched that dream turn into a nightmare as I moved through the ghettos of the nation and saw my black brothers and sisters perishing on a lonely island of poverty in the midst of a vast ocean of material prosperity, and saw the nation doing nothing to grapple with the Negroes’ problem of poverty. I saw that dream turn into a nightmare as I watched my black brothers and sisters in the midst of anger and understandable outrage, in the midst of their hurt, in the midst of their disappointment, turn to misguided riots to try to solve that problem. I saw that dream turn into a nightmare as I watched the war in Vietnam escalating…. Yes, I am personally the victim of deferred dreams, of blasted hopes.

At the end of their lives, their trajectories were converging, with Martin revealing his radical side and Malcolm becoming much more inclusive and open to working in coalition for the human rights of all people.

And as we prepare to go deeper into how Dr. King and Malcolm X influenced one another, I would be remiss if I failed to mention that Martin and Malcolm did actually meet one time in person, on Thursday, March 26, 1964 at a building that has been at the center of recent headlines: the United States Capital. The House of Representatives had passed the Civil Rights Act, but the bill was being filibustered in the Senate (1).

After Dr. King gave a press conference, one of Malcolm X’s assistants made sure they not only ran into one another, but also did so in front of the press corp. Dr. King did not expect to encounter Malcolm X that day, but without hesitation he extended his hand and said, “Well, Malcolm, good to see you.” Malcom accepted his handshake, and said, “Good to see you.” They proceeded to walk and talk down the halls of the Senate while the press corp took pictures (183-184).

Looking ahead,

Martin and Malcolm would never develop a personal friendship, but their political visions would grow closer together throughout their lives. A mythology surrounds the legacies of Martin and Malcolm. King is most comfortably portrayed as the nonviolent insider, while Malcolm is characterized as a by-any-means-necessary political renegade. (7)

But the messier, more complex reality is that toward the end of their respective lives, Malcolm was becoming an increasingly savvy political operative open to building coalitions with white allies, and Martin was becoming an increasingly radical social prophet (195, 235).

And even as I think it is important to emphasize their intellectual and activist convergence, let me say just a little about some of their important difference in methods. Malcom said, in 1962, “I’ll never take part in a sit-in, because if someone forces me with a club or attacks, I would have to rely on my equity, my God-given rights, and use the same force in retaliation” (122). Similarly, two years later in 1964, the same year that Dr. King was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, Malcolm said, “Black people shouldn’t be willing to be nonviolent unless white people are going to be nonviolent” (222). And even though I deeply respect the nonviolent approach of Dr. King and Gandhi, I can also hear where Malcolm X was coming from.

With that being said, let me also give you another important but less-often told story about their increasing collegiality and intellectual convergence. The very next year, in 1965, when Dr. King was in jail during part of the Selma to Montgomery Marches, Malcolm X was also in town, and spoke privately to Dr. King’s wife, Coretta. Malcolm said,

Mrs. King, will you tell Dr. King that I’m sorry I won’t get to see him? I had planned to visit him in jail, but I have to leave. I want him to know that I didn’t come to make his job more difficult. I thought that if the white people understood what the alternative was that they would be willing to listen to Dr. King” (225).

Clearly, there was a profound respect between Dr. King and Malcolm X in spite of their differences.

I will plan to say more about both Dr. King and Malcolm X in future years, but for now, as I begin to move toward my conclusion, if anyone wants to dive deeper into the details, a good starting point is historian Peniel Joseph’s recent book, The Sword and the Shield: The Revolutionary Lives of Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr. James Cone’s earlier study, Martin & Malcolm & America, is also powerful.

But before either of those books, the first person to blaze the ground we have been exploring was, unsurprisingly, James Baldwin: “Perhaps no other person spent more time, respectively, with Malcolm and Martin than James Baldwin” (307). And in 1972, Baldwin published a moving and insightful essay in Esquire magazine titled “Martin and Malcolm.”

I’ll share with you just a few lines:

By the time each met his death, there was practically no difference between them…. What made [Malcolm] unfamiliar and dangerous was not his hatred of white people but his love of blacks, his apprehension of the horror of the black condition, and the reasons for it, and his determination so to work on their hearts and minds that they would be enabled to see their condition and change it for themselves. (304-305)

Dr. Joseph adds an important gloss on Baldwin’s perspective that, “Baldwin remembered Malcolm as a master teacher who believed in black dignity even when most Negroes would not dare to…. And King believed in the idea of America more than the nation did” (305).

Today, the twin legacies of Dr. King and Malcolm X—as well as so many other racial justice activists surrounding them—challenge us to create a world that truly recognizes, celebrates, and supports what the UU First Principle calls “the inherent worth and dignity of every person.” They were both taken from us far too soon, but if you want to know what Dr. King would likely be doing or saying if he were alive today to celebrate his 92nd birthday, look at what The Rev. Dr. William Barber is doing and saying through the revitalized Poor People’s Campaign (poorpeoplescampaign.org).

It’s also significant to note that Raphael Warnock (1969 – ), born the year after Dr. King was assassinated, is now both the senior pastor of Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta (where Dr. King was co-pastor in the final decade of his life) and the senator-elect from GA. Rev. Warnock is another person we can look to as an example of what Dr. King might be doing and saying if he were still alive today.

If you want to know what Malcolm X would likely be doing and saying if he were still with us—especially the person and leader Malcolm was becoming at the end of his life—look at what the #BlackLivesMatter movement is doing and saying (blacklivesmatter.com).

For now, I’ll leave the final word to James Cone— from the end of his book, Martin & Malcolm & America, which speaks to the legacy that both Martin and Malcolm leave us with today:

We must declare where we stand

on the great issues of our time.

Racism is one of them.

Poverty is another.

Sexism another.

Class exploitation another.

Imperialism another.

We must break the cycle of violence

in America and

around the world.

Human beings are meant for life and not death.

[We] are meant for freedom

and not [enslavement]….

We must break down the barriers

that separate [us] from one another.

For Malcolm and Martin,

for America and the world, and

for all who have given their lives

in the struggle for justice,

let us direct our fight toward one goal—

the beloved community… (318)

In that spirit, let us join together in a coalition for collective liberation—through which we all get free.

The Rev. Dr. Carl Gregg is a certified spiritual director, a D.Min. graduate of San Francisco Theological Seminary, and the minister of the Unitarian Universalist Congregation of Frederick, Maryland. Follow him on Facebook (facebook.com/carlgregg) and Twitter (@carlgregg).

Learn more about Unitarian Universalism: http://www.uua.org/beliefs/principles