A Pagan myth of Christian origins, of pagan inception

As Neo paganismmatures, the unveiling of several layers of history and mythologising are gradually peeled away, revealing some fascinating and telling truths. Much of the pagan myths we live with today tend to be borne out of the romanticising of the Victorian era, and unfortunately reflect much of the fantasising and speculation that accompanied it. However, through the decades of living this paganism, certain truths have become regularised within the structures of the pagan current, developing a recognisable thematic basis for identifying NeoPagan mythology as a living tradition of experience.

As the feast of the Vernal Equinox approached, I put together a piece that explores the tradition of Lady Day, March 25th, in traditional witchcraft (read this post here). When writing such things, I am aware that it brings up the contentious issue of Christianity and I am acutely conscious that the modern pagan quite frequently has some deep felt animosity, or at least some mild distaste, towards such. This is intended in no way as an apology, rather I felt that it was important to achieve some level ground as the modern pagan movement attains its adolescence and is seasoned enough now to allow a lifting of some of the veils to peer beneath. What we may find might not be what we expect or want to see, but nevertheless a healthy reconciliation must be achieved if we are to advance.

The myth of the year is a central architecture upon which the modern pagan paradigm hangs, acknowledging the annual cycles of flux and reflux as reflective of the greater passage of time within our own lives – as above, so below. Thus, microcosmic and macrocosmic cycles are harmonised and the revelatory process of the mystery worked upon. Study of the ancient mystery traditions, such as those at Eluesis, indicate that this is a pattern feature common then as it is adopted and reworked to suit today. The model of Demeter and Persephone and the descent of the Maid (Kore) into Hades, thereby marking the onset of the dark half of the year, is often acknowledged as the root of the modern Pagan myth, as is that or Osiris and Isis. However, it is perhaps more likely that the origin of our contemporary narrative may be a little closer to home, and the ancient should be sought to ratify its truth.

Lady Day, 25th March, is an approximation of Equinoctial observations thus marking the quickening and threshold of light (or darkness) achieving dominance over a 24 hour period. In the traditional calendar of Britain, this is known as a Quarter Day, that is a day which quarters the year and therefore stands at one of the four pillars that carry the heavens above the earth. The remaining three are Midsummer (24th June), Michaelmas Day (September 29th) and Christmas Day (25th December) and are frequently named as the festivals of Traditional Witchcraft adherents between the major feasts at the cross quarters. These days were calculated as equidistant from each other and form a perfect cross. This is not without significant, nor is it by coincidence and we cannot gloss over this fact.

In modern paganism, we tend to allocate our four quarter festivals with the solar stations, which align as near as possible to the actual timing of the equinoxes and solstices. That these were originally aligned can be easily explained as the traditional Julian calendar in England was replaced in 1752, when everybody went to bed on 2nd September and awoke on the 14th. This resulted in feast days we now designate as ‘Old’ as in Old Christmas Day 6th January. The Julian Calendar was originally aligned with the equinoxes and solstices as modern pagans would have it but, as the calendar was marred in its calculations of the precise length of the year, the original correspondence to astronomical events shifted as time progressed.

For example, in 45 the equinox fell on March 25 (see alsoAnnunciation). By the time the Council of Nicea met in 325 A . D . to determine the date of Easter, spring equinox was falling on March 21. (https://encyclopedia2.thefreedictionary.com/Old+Christmas+Day)

This is telling as it suggests that the origins of the quarter festivals do not originate in the ancient mysteries of Eleusis but, in fact, the ancient Christian mysteries (queue dramatic music). It also occurred in the adoption of the Gregorian calendar that New Year’s Day shifted from March 25th to January 1st by Britain and its colonies, which at this time included North America before the Revolution.

So, to recap thus far, the year was originally marked in the old calendar by four quarter days which represented the pillars that separated heaven and earth and were aligned to the equinoxes and solstices. Whilst it is a worthwhile pursuit uncovering ancient pagan, European and shamanic sources for this, nevertheless it is imperative that we keep in mind that this was not only the folk calendar but the official and municipal means of marking time. We would love to think of some packet of pagans keeping old beliefs alive but the truth is, everybody lived under these observations (and their inherent errors which moved the dates farther from the solar station) until the modern era as was the custom. In rural Britain, it is extremely unlikely that one could have found a labourer at a quarter day fair, looking to renew his contract with a landlord, who was deliberately acknowledging a pagan festival or gods. These were folk customs firmly established in a Christian European habitus and, therefore, it was inconceivable to the mind of those working class people to contemplate any pagan source. That being said, it was equally common historically for those living within a nominally Christian world to readily have incorporated old heroes and deities into their worldview without challenge to the commonly held habitus. For example, the Book of Oberon, an Elizabethan operative grimoire, recounts multiple prayers and invocations alongside rubric for evoking Oberon as King of the Fairies, as well as the Queen of Elfame and her attendant train. Similarly, the Orphic Mysteries find a new home in medieval literature as Sir Orfeo, an anonymous epic poem, as well as myriad folk songs and references. This does not, necessarily, suggest the transport of ancient paganism through time, but rather the survival of popular motifs and themes synchronised within the myth narrative by which people lived. None of the aforementioned challenged the notion of the supremacy of Jesus and the Christian narrative.

This all seems, at this point, to be suggesting that we should be adopting a Christian worldview and that is not what I am implying. Rather, as paganism grows up, it is incumbent upon its adherents to become mature enough to recognise its development for what it is and the history which informs it, making it stronger and more resilient to change, which is measured as Time. This has become more and more evident today as we find a type of Christian perspective within, for example,, modern Druidry with many renowned Druids acknowledging the mystical nature and being of Christ. In addition, as we plunder the grimoires and other legitimate magical documents of the past, it is impossible to be unaware of the Christian world which permeates the writer’s perspective. These works do, however, allow us to peak beneath the veneer that even the composer of such works was perhaps unaware of, or upheld a worldview that would not permit such observation in its scope.

Uncovering the ancestral paganism in the Christian past

Unlike our medieval forebears, our worldview has been liberated of many of the shackles which restricted thought and, after the Enlightenment, a paradigm shift occurred. Therefore, people became more conscious of the world operating around them and its functions, climaxing in the Victorian romanticism previously discussed which imagined a lost ‘Golden Age’.

We are now in a position to be able to approach the past and the myth of the year with greater clarity and, when considering all the work available, allow for the startlingly apparent Christian influence within the context of our feasts. That is not to say that we become Christian, but that we must not disallow those elements in our own history or mythology, or become subject to repeating the same mistakes of the fallacy of a supreme world view. When new religions emerge, it is common that fundamental elements react against the old. This can be seen, for example, in those early Christians who pillaged the Library of the Serapeum in Alexandria and defaced pagan statues in the Agora. We must not fall into the same trap and deface the Christian edifice, to which modern paganism could be the heir apparent in a mature, intellectually and emotionally robust world. The names of older Gods are evident in the Christian worlds, as are the myths that perpetuate our annual cycles, which are based predominantly on pagan Roman festivals.

The liturgical year of the Christian world observes, historically, the mystery of the birth and death of Jesus, as the Christ, upon the same day, separated by twelve months (one for each apostle who symbolise the zodiac). On the 25th March, anciently aligned with the Vernal Equinox, the eternal and impermanent, that is the spiritual and the material, become unified in the Incarnation. Spirit descends from heaven and becomes incarnate upon earth. At the same time, night is equal to day and the impermanent becomes eternal, that is spirit divides itself from the manifest. Thereby, the mystery of the Vernal Equinox commences in the conception and death of Christ in the Christian myth of the year. The equinox here forms a null point, whereby light and dark are of equal duration and reconcile the truths of Life and Death in one liminal moment, a threshold or opening in the year. Significantly, the Vernal Equinox marks the ascendancy of the light, as opposed to its Autumnal twin which embodies descent into darkness. However, at the time of the Vernal Equinox, light and darkness are equals and thus create that void, possessed in a single expression all potentiality.

Following the Vernal Equinox, the church year observes the journey of the Christ through the year, culminating in the Crucifixion, which also is the Incarnation and the whole begins again. Sound familiar? It should as the theme of death and resurrection. Augustine of Hippo was among the first to observe such a point as being under the aegis of the feminine principle in that it is the Grace filled Mary that is the mother, and it is the Mary that weeps at the death. She is present and implicated in both the moment of death and conception when spirit and matter experience the ingress, congress and egress, or, as Augustine puts it the womb and tomb, the emerging from and return to the darkness of Herself. In alchemical terms, this is the Flamel Cross, signified by the term ‘fixing the volatile‘, whereby spirit, the eternal, is made impermanent in the material – symbolised by a serpent entwined, or else nailed, to a cross (sometimes a Tau Cross).

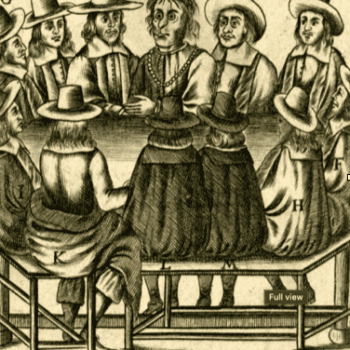

The image from Robert Fludd’s Medicina Catholica (Adam McLean’s Alchemy Website) depicts man seated in a castle of four towers, at which the winds reside symbolised by the angelic genius which rules them. Between Oriens in the East and Egyn in the North is the abode of of the Godhead, depicted in the Tetragrammaton YHVH as heaven analogous with the cloud. It goes without saying that this location is in the area where the rising sun emerges upon the horizon and marks the beginning of the period of lightness in ascendancy in the mythic calendar. Observe how the Christian alchemist depicts the ancient wind gods, as well as the angelic forces which are named for demons found in the Grimoire lists of spirits and, as Jake Stratton Kent has observed, perhaps relating to older deities of a more pagan time. Furthermore, we might see in this woodcut an aspect of the mystery as described in the Book of Revelations, upon which Peter Grey has expertly written in Apocalyptic Witchcraft.

Within Modern Traditional Witchcraft, this image readily calls to mind the Compass, which is the means by which the worlds are traversed, as well as the location and destination itself. In this way, it functions very much like the Qabbalist Merkavah chariot, and shares its technology closely with the revelatory myths of Ezekiel and John of Patmos. If we dismiss these works as Christian, and opposed to our paradigm, we risk losing not just the bath water but the baby too. One of the best ways to work the Compass is in acknowledging the passing through the ‘nine knots of the year’ of Traditional Witchcraft made popular by Robert Cochrane and his Clan of Tubal Cain (now headed by Shani Oates as holder of the Virtue).

Working the Myth of the Year through the Compass

The Compass is built up through its operation, and that works with ordinary time as well as the eternal moment, Kairos (which, incidentally, also means weather in ancient Greek). In journeying through the mythic cycles, we engage directly with the Compass and its inherent spirits and travel through the realms which open us ultimately to the ‘other’. An actual compass, in conjunction with a timepiece, is used to locate a position on a map or landscape and it is the same with traditional witchcraft. Time is the great destroyer, the serpent as ouroboros, which encompasses the third dimensional reality. Therefore, it stands to reason that we must venture forth from space-time as our conscious awareness most closely perceives the four-dimensional continuum, which may be philosophically designated Tetragrammaton, the Demiurge, or Tettens, the Saturnian Lord of the Wind Gods. So, by marking Time and identifying North, we establish our compass as the tool of navigating, which becomes the vehicle as well as the mythological landscape itself.

Symbolically, this can be identified in the language of Revelations of John of Patmos (sans the negative emotions that clearly affected John), Ezekiel, Merkavah and Hekhalot traditions which all exist in our times from Judea-Christian beliefs. That does not make them Christian, per se, and most Jewish and Christian adherents would variously throughout history condemn the use of these magics, as Kabbalah and Witchcraft, and a direct threat to the grip of the man-made structures which dominate and control the populace.

We have peeled back the modern Neopagan layer to uncover a historically Christian one, but what lies beneath? Inevitably, it is to the Hellenic world that we now turn and in which Judaism lived and Christianity was born. Those years millennia ago were dominated by a distinctly Graeco-Egyptian flavour which informs our world even today.

Of course, we should most likely be familiar with the concepts here and there is a wealth of material available to students who wish to learn yet more about these Hellenic pagan origins. These will not be discoursed further here to save from making too lengthy a writing and to allow the reader to be at ease with the more familiar source of the pagan history which informs our modern tradition. The purpose here has been to tread a direct path to that point within the Pagan Hellenic world of our spiritual ancestors and find the thread that leads us here, which must unavoidably take us through highly Christianised territory. No longer can we ignore the path modern Paganism has trod to get here and it benefits us to embrace those parts that compose it which we may have found anathema previously. It is not necessary to convert to, nor reject Christianity in order to mature our paganism, but it is imperative that we acknowledge its contribution to the mythologies we live by if we are going to be a progressive movement that is rapidly establishing itself as a religion of this millennium, with its own myths that represent a holism.

In this I echoe John Beckett’s words, “It’s time for a healthy balance to be restored.”