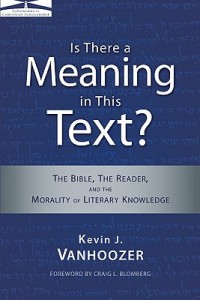

In Kevin Vanhoozer’s landmark book, Is There a Meaning in This Text?, he ends the 500-page tome with two sins that we can easily commit in trying to interpret Scripture (pp. 462-463):

In Kevin Vanhoozer’s landmark book, Is There a Meaning in This Text?, he ends the 500-page tome with two sins that we can easily commit in trying to interpret Scripture (pp. 462-463):

1. Pride. “It is the sin of conservative and liberal alike, for pride knows neither party nor denominational boundaries. … [It] encourages us to think that we have got the correct meaning before we have made the appropriate effort to recover it. … Pride neglects the voice of the other in favor of its own.”

2. Sloth. “Interpretive sloth is a kind of shadow image of interpretive pride, its evil twin. Whereas pride claims knowledge prematurely, sloth prematurely claims the impossibility of literary knowledge. … Make no mistake: interpretive sloth is every bit as deadly as pride, for sloth breeds indifference, inattentiveness, and inaction.”

Particularly in Christian hermeneutics, in dealing with God’s Word, it is crucial to be aware of these dangers. First, pride can exacerbate the main issue for anyone seeking to understand Scripture: presuppositions. We come to the text with meaning in-hand, seeking to do the hard work of exegesis without having the humility to be wrong if the text leads us away from our presupposition. While bringing theological and exegetical baggage to the text is unavoidable, we can and should seek objectivity anyway. We can, if we are careful, leave at least some of our baggage at the door, stepping into the hermeneutical house with the Spirit as our guide and an open mind as our posture.

Second, sloth can leave us in our presuppositions without any attempt at letting the Spirit work through our efforts to grow us as interpreters. This is especially true of those who enjoy sermons and books. We would much rather let our favorite preacher or author tell us what a text means–especially when it fits our presuppositions–rather than putting in the hard work that our favorite muse assumedly put in. Instead, we could dive into the text with the joyful conviction that God has something meaningful to say to us.

We should come to the text with ourselves in mind (self-awareness and self-critique) and with God’s message in mind (what is the author/Author’s actual meaning, point, and application of this text?). Your hermeneutical method will never be perfect, but it doesn’t have to be static or stagnant.

Vanhoozer concludes (p. 466):

“A hermeneutics of humility and conviction. We must hold these two aspects together in a constructive tension. Emphasize one without the other, and you quickly fall prey to one or the other of the two deadly interpretive sins. Emphasize the two together, and you are able to avoid hermeneutic dogmatism and skepticism alike.”