Have you ever felt overwhelmed at the number of choices to buy a salad dressing at the grocery store? Have you ever failed to choose a health care or retirement option just because, well, there were so many options that you couldn’t pick one? Have you ever searched and searched for the perfect pair of shoes, the best dress for a special event, or a new car, and then made a choice but still felt like maybe you could have found something even better?

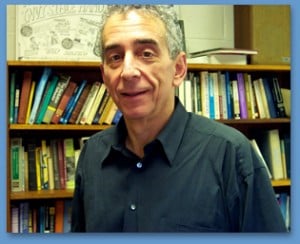

If you answered “yes’ to any of these questions, then you are suffering from what Swarthmore psychology professor Barry Schwartz calls “The Paradox of Choice.” As he recounts in this TED lecture, Schwartz suffered so much agony when buying a pair of jeans that he decided to write a whole book explaining how Americans mistakenly think that more choices means more freedom and that more freedom means more well-being.

One of the first-year students in my positive sociology seminar wrote a review of Schwartz’s book The Paradox of Choice: Why More is Less, and to my amazement my students were so persuaded by his arguments about the negative effects of too many choices on our well-being that they all shouted in a chorus at the end of class, “No more choices, please! Save us from our misery!”

One student admitted (somewhat embarrassed) that she was having trouble picking out her new glasses. She had already taken 3 female friends with her to pick out new frames; but still feeling unsatisfied, she invited 3 male friends. This same student lamented how others’ inability to choose made her miserable, “I mean, I really hate it when a guy asks me out on a date and then asks me to choose where to go!” Another student chimed in, “My stepmother always wants to buy me the perfect Christmas gift. So we go shopping for days and days and I pick out lots of things I like. But she can’t make a choice, so I end up getting nothing even though I told her I really, really wanted something!” A third student said, “No one wants to make plans when we go out with our friends because no one wants to be responsible if we don’t have fun.”

After our engaging class discussion, the student who had led the class discussion asked me, “So do you want to read this draft and discuss it on Monday? Or do you want me to revise it over the weekend and send you a new draft before we meet to discuss it?” My immediate reaction was to say, “Whichever you choose.” But when her face sunk, I quickly realized I was doing what Schwartz calls abdicating authority–when a professional such a doctor or a professor won’t tell a patient or student what to do. I corrected myself saying, “You want me to tell you what to do, don’t you?” and she nodded her head.”So why don’t you outline some revisions you think you could make, and we can discuss this draft and your plan for revision on Monday.”

Schwartz offers three main reasons for the paradox that having so many choices makes us unhappy: 1) Paralysis. We have so many options we don’t pick any of them. Just ask yourself–when was the last time you went to the store to buy something supposedly simple, like dishwashing liquid, and felt so overwhelmed by the choices you just walked out of the stores? 2) Opportunity Costs. When we have seemingly endless options, we find it hard to be satisfied with what we do choose. Even worse, when do make a choice, we can always come up with an ‘imagined alternative’ that reduces our satisfaction with even our good decisions. Regret, not happiness, goes up when we have too many choices. 3) Escalation of Expectations. Even if we objectively make a better choice than we could have before we had so many choices, we feel worse. Why? Well, those shoes I bought last week may be the best pair I’ve ever had, but with so many great shoes at Nordstrom’s, Macy’s, and on-line how do I know I got my dream shoes, the absolutely perfect pair of shoes I want to wear until the end of my life? To explain this regret-at-having-it-so-good-we-feel-worse, Schwartz quips in his TED lecture, “Everything was better when everything was worse.” We have become such perfectionists that we are never pleasantly surprised by what we have.

Much research in psychology, sociology and particular economics falls into this problem: our concept of the human person is a being who uses his or her reason to satisfy his or her preferences (i.e., the utility-maximizing rational choice actor). Sociologist Margaret Archer, in her book Being Human: The Problem of Agency, argues that satisfying preferences is not the same as satisfying the person. The human person, Archer persuasively argues, is driven by ultimate concerns, such as concerns for love, beauty and truth. We can’t satisfy those concerns no matter how many choices we have, as human persons ultimately are capable of imagining a better, happier, more beautiful world than any choice we have in front of us, an imaginative power Archer argues is key to positive social transformation.

Perhaps the most important lesson my students learned in positive sociology, as they told me, is that the the human person finds deep satisfaction through strong relationships with others and by having a deep sense of meaning in which one’s purpose in this life is tied to a larger narrative. Deciding where to go out on Friday, where to go out on a date, what glasses to buy, and what classes to take makes my students unhappy rather than happy. Given that I had never taught positive psychology or positive sociology before, my students ended the semester pleasantly surprised with what they got, probably because they had no idea what to expect and because they learned had many practical lessons for how to be happier.