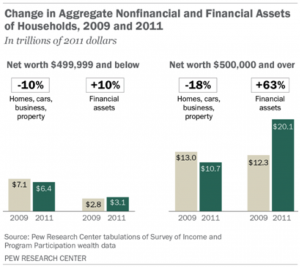

Last week, the Pew Research Center released a report showing wealth has dropped for the bottom 93% of Americans, but for those with wealth levels over about $890,000, wealth has risen by an average of 28% in the last two years. As the economy starts to recover, it’s clear who is winning and who is losing ground.

Globally, inequality between countries seems to be decreasing, although it’s increasing within countries—and overall. And one of the biggest drivers of the growth of inequality is the growth in wealth of those with the highest incomes.

Elsewhere I’ve blogged about some of the problems with inequality in terms of social and economic outcomes. An opinion piece by Sean Reardon in the NYT shows that educational outcomes are becoming more divergent for the upper and lower classes, within the United States. While school funding is not the key issue he highlights, it’s part of the story. In Philadelphia, public schools are looking at cuts of 25%—this translates into the removal of counselors and programs, and increasing class sizes above 30.

In the classes I teach on social change and globalization, students leave class discouraged many days. We spent one session focused on the conditions and power held by many workers involved in different commodities around the world. We discussed coffee (John Talbot,’s Grounds for Agreement), maize (Elizabeth Fitting’s The Struggle for Maize), tomatoes (Deborah Bardnt’s Tangled Routes), and cotton (Koray Caliskan’s Market Threads). The story of the lack of power held by workers in each of these commodity trades is a consistent theme, and one that can be a struggle to engage.

Sometimes I hear students talking about ethical business or business as mission. I’d love to see these conversations intersect more with those on issues of inequality. Many conceptions of ethical business often revolve around principles like giving back, not cheating, or refusing to actively exploit others. Yet we rarely think about the distribution of profits, or how businesses and actors are contributing (or challenging) the growing inequality in power held by people around the world.

While many are not thinking in those terms, others area, and I want to highlight one of those cases. I recently had an article published in Latin American Research Review, where I describe the ways some Central American coffee actors think about ethical business practices. They had both a broader view of what ethical commitments mean, as well as a more integrated understanding of how issues of power and the Gospel are intertwined.

While these evangelicals gave money to their community, and volunteered time to mentoring youth, that was not the central way they practiced social responsibility. They prioritized increasing the value-added nature of work done by coffee farmers. They did this through agricultural training, but also by challenging some current market structures and dynamics. As one of the leaders suggested, the way they demonstrated their faith was to “introduce values—Christian values, Christian ethics, transparency, and stewardship.” For them, this meant recognizing that current business practices accepted in the coffee sector had to be challenged.

Giving to those in need may just exacerbate high power and wealth differentials. It’s no surprise that these same actors I interviewed in Central America were critical of US Christian responses to give aid to farmers instead of simply paying higher prices for a product. For them, to be ethical meant to think about transforming the ways business worked. In my next research project, I’m gathering data to look at how the over $2.3 billion per year from U.S. religious humanitarian organizations is spent in dealing with poverty, and how common (or uncommon) this example from Central America is. As inequality levels continue to rise, and power becomes more concentrated in the hands of a few, Christians need to be thinking more critically about what it means to engage in ethical practices in our economy.