(Part 1 in a series on Evangelical Christianity in America)

There is much confusion about Evangelical Christianity in America, including very basic questions such as: What is it? Who are Evangelical Christians? What do they believe? How is it changing? And so forth.

So, I thought that I would start a series, guaranteed to run as long as I feel like writing about it, that simply describes the basics of Evangelical Christianity in modern-day America.

Let’s start with perhaps the most basic of questions: What is Evangelical Christianity?

There is no one answer to even this the most simple of questions, though there are fundamental characteristics associated with it.

Historian David Bebbington defines Evangelical Christianity as having four main qualities (quoted from here):

* Biblicism, a particular regard for the Bible (e.g. all essential spiritual truth is to be found in its pages)

* Crucicentrism, a focus on the atoning work of Christ on the cross

* Conversionism, the belief that human beings need to be converted

* Activism, the belief that the gospel needs to be expressed in effort

Theologian John Stackhouse has a nice discussion of the theological aspects of the term here.

Sociologist Brian Steensland and colleagues point to these characteristics: “Evangelical denominations have typically sought more separation from the broader culture, emphasized missionary activity and individual conversion, and taught strict adherence to particular religious doctrines.”

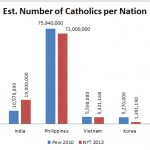

As commonly used, Evangelical Christianity refers to Protestants only, and I will follow that convention, though there’s no reason that the general definition of Evangelicalism can’t apply to Catholics as well. In fact, Pope Francis has been labeled an “Evangelical Catholic.”

Here is where things get tricky: How do we measure Evangelical Christianity? That is, how do we know who is one and who isn’t one?

The most commonly-used approach is scholarly research is to look at religious affiliation and define Evangelical Christianity at a denominational level. So, people who go to “Evangelical” Protestant denominations are themselves Evangelicals. But… there are different approaches to doing this.

One affiliation-based approach, developed by Steensland et al., divides Protestants into three traditions: Evangelical, Mainline, and Historically Black. Evangelicals tend to be more conservative both socially and theologically, Mainline tend to be more liberal on both, and Historically Black tend to be theologically conservative and socially liberal.

A second popular affiliation-based approach, however, refers to “conservative” protestants and contrasts them with “moderate” and “liberal” protestants. Conservative protestants and then broken into different groups, including evangelicals, fundamentalists, and charismatics.

The term “conservative protestant” in the second approach is roughly equivalent to “evangelical” in the first approach.

Which is the better approach? I tend to use the first approach since its measurement characteristics are reasonably well supported in empirical studies; however, both approaches have their problems. With the first approach, many of the people defined as Evangelical don’t identify with that term themselves (a point I’ll return to below). With the second approach, many conservative protestants are conservative in theology but liberal in politics and social issues, so painting them with the broad brush of conservatism overstates matters.

To complicate matters further, journalists and other people in public discourse (and even some scholars) use a variety of terms as synonymous with evangelical/conservative protestant, including “fundamentalist,” “born-again,” and “religious right.” Others, however, give each of these terms more precise meaning.

As a second general approach, some scholars focus on identity. To them, Evangelical Christians are people who say they are Evangelical Christians.

As a second general approach, some scholars focus on identity. To them, Evangelical Christians are people who say they are Evangelical Christians.

With other religious traditions, affiliation and identity measures yield about the same results. For example, people in the Catholic church usually think of themselves as Catholics. However, as discussed above, many people involved in Evangelical churches identify with other labels, such as “born-again Christian” or “non-denominational Christian.”

Conceptually, identity and affiliation are two different matters. For example, I live in New England (Connecticut’s state motto: “We’re between New York and Boston), but I don’t identify myself as a New Englander–still a Californian. So, at some level, whether we look at identity or affiliation depends on which aspect of the religious experience we’re interested in.

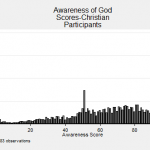

As a third general approach, a well-known marketing firm–The Barna Group–uses theological questions to identify Evangelical Christians. They start with two theology questions to identify born-again Christians. Then, among born-again Christians, they use seven more theology questions to identify Evangelical Christians. For example, one of the seven questions regards “believing that Jesus Christ lived a sinless life on earth.”

I don’t know of any scholars who use this 9-question theology test to define evangelicals, and it strikes me as convoluted and of unknown measurement qualities.

The different uses of the term Evangelical lead to all sorts of confusion. For example, using affiliation-based definition, about 25% of Americans are Evangelical Christians. But, using identity- or theology-based definitions, the number drops to 8%-15%.

What does all of this mean for the person wanting to learn about Evangelical Christianity? Basically, in reading any information about Evangelical Christianity, you, the reader, have to first assess how the author is using the term. It means more work for you, but it’s necessary for understanding what’s going on.

Enough confusing terminology! My upcoming posts will have cool graphs and numbers that demonstrate how Evangelical Christianity (as defined in the first affiliation-based approach) is doing.

(P.S., we bloggers are told that we need to add pictures to enhance our posts. But, I have no idea of how to visually illustrate an operational definition, so I just added a picture of a cute kitten).