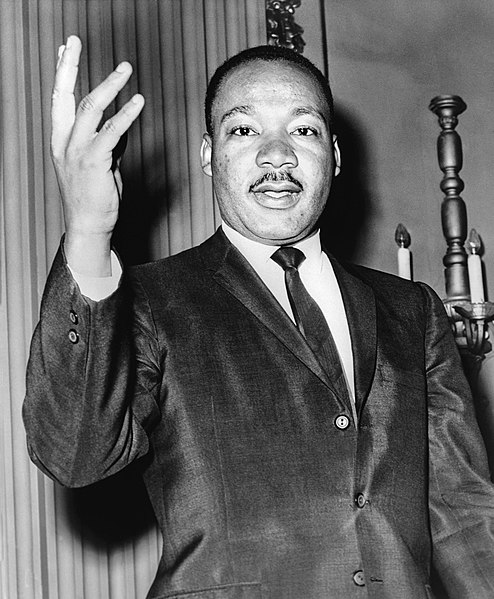

While still recovering from the flu (yes I still got it despite getting a shot last November) I have tried to keep my intellectual capacities running if only through reading and not much writing. In a few days we as a nation will remember the Reverend Martin Luther King and his major contributions to American society. I confess that my awareness of King is not very systematic, and I am reminded every semester how much less each generation seems to know of him and his legacy. Dr. King gave many speeches over his brief public career, and recently the American Psychological Association posted his address to this organization and to all American social scientists. As the webpage summary puts into context, this speech was delivered on September 1, 1967. Seven months later, his talk was about to be published in the Journal of Social Issues (Vol. 24- still running today) when the news rang out of his assassination in Memphis, TN.

While still recovering from the flu (yes I still got it despite getting a shot last November) I have tried to keep my intellectual capacities running if only through reading and not much writing. In a few days we as a nation will remember the Reverend Martin Luther King and his major contributions to American society. I confess that my awareness of King is not very systematic, and I am reminded every semester how much less each generation seems to know of him and his legacy. Dr. King gave many speeches over his brief public career, and recently the American Psychological Association posted his address to this organization and to all American social scientists. As the webpage summary puts into context, this speech was delivered on September 1, 1967. Seven months later, his talk was about to be published in the Journal of Social Issues (Vol. 24- still running today) when the news rang out of his assassination in Memphis, TN.

It’s worth a read for those interested in the way one of the great leaders of the 20th century brought together global conflict, social scientific research, and contemporary national issues together for an audience of social scientists. The Rev. Dr. King did not hold back his criticism of the efforts of social scientists, particularly sociologists, who likely supported the cause but had radically different solutions. I mention both of titles of “Rev.” and “Dr.” because as you will see these credentials were not without warrant. He is one of the few I have seen to deftly combine theological concepts with social science and politics. In the following I share some of the quotes from his speech. King first opens up with the importance of social science research for the African American and white communities:

If the Negro needs social sciences for direction and for self-understanding, the white society is in even more urgent need. White America needs to understand that it is poisoned to its soul by racism and the understanding needs to be carefully documented and consequently more difficult to reject. The present crisis arises because although it is historically imperative that our society take the next step to equality, we find ourselves psychologically and socially imprisoned. All too many white Americans are horrified not with conditions of Negro life but with the product of these conditions-the Negro himself.

He then retells the events of the past 15 years (1950s-1967) and one of the major consequences of addressing racism head on:

The decade of 1955 to 1965, with its constructive elements, misled us. Everyone, activists and social scientists, underestimated the amount of violence and rage Negroes were suppressing and the amount of bigotry the white majority was disguising.

Science should have been employed more fully to warn us that the Negro, after 350 years of handicaps, mired in an intricate network of contemporary barriers, could not be ushered into equality by tentative and superficial changes.

King was keenly aware of the way social scientists think and introduced institutional racism into the conversation. While many social scientists advocated change, few of the applications of that advocacy anticipated what would happen next. Urban riots were rampant especially in northern cities and King notes that systemic racism as the cultural context in which these events occur. Quoting from Victor Hugo (yes the one who wrote Les Miserables)

A profound judgment of today’s riots was expressed by Victor Hugo a century ago. He said, ‘If a soul is left in the darkness, sins will be committed. The guilty one is not he who commits the sin, but he who causes the darkness.’

In an unexpected (to me) turn, he then addresses the problematic American presence in Vietnam. It is at this point that he utters the phrase seen on many bumper stickers and Facebook memes:

It is my deep conviction that justice is indivisible, that injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.

King mentions Vietnam through a play on the word segregation. As he states: “I can only respond that I have fought too hard and long to end segregated public accommodations to segregate my own moral concerns.” King was clearly seeing a much bigger picture in his last years connecting the struggle for equality in America with the struggles for equality throughout the world, and perhaps more specifically for a more just world when the powerful manipulate, exploit and kill the less powerful. Several paragraphs later, King turns his attention to the social scientific community:

Now there are many roles for social scientists in meeting these problems. Kenneth Clark has said that Negroes are moved by a suicide instinct in riots and Negroes know there is a tragic truth in this observation. Social scientists should also disclose the suicide instinct that governs the administration and Congress in their total failure to respond constructively.

Social science may be able to search out some answers to the problem of Negro leadership. E. Franklin Frazier, in his profound work, Black Bourgeoisie, laid painfully bare the tendency of the upwardly mobile Negro to separate from his community, divorce himself from responsibility to it, while failing to gain acceptance in the white community. There has been significant improvements from the days Frazier researched, but anyone knowledgeable about Negro life knows its middle class is not yet bearing its weight. Every riot has carried strong overtone of hostility of lower class Negroes toward the affluent Negro and vice versa. No contemporary study of scientific depth has totally studied this problem. Social science should be able to suggest mechanisms to create a wholesome black unity and a sense of peoplehood while the process of integration proceeds.

As one example of this gap in research, there are no studies, to my knowledge, to explain adequately the absence of Negro trade union leadership. Eight-five percent of Negroes are working people. Some two million are in trade unions but in 50 years we have produced only one national leader-A. Philip Randolph.

Discrimination explains a great deal, but not everything. The picture is so dark even a few rays of light may signal a useful direction.

I wonder if King would have been pleased with the social science research that emerged 20 years after his passing showing the effects of racial and class segregation. King’s second area that social scientists could support the civil rights cause was in political action. He cited several studies that have examined political activism (i.e. galvanizing more African Americans to vote and create a bloc):

The need for a penetrating massive scientific study of this subject cannot be overstated. Lipset in 1957 asserted that a limitation in focus in political sociology has resulted in a failure of much contemporary research to consider a number of significant theoretical questions. The time is short for social science to illuminate this critically important area. If the main thrust of Negro effort has been, and remains, substantially irrelevant, we may be facing an agonizing crisis of tactical theory.

His third area of research he suggested was psychological and ideological change among African Americans.

Social science is needed to explain where this development is going to take us. Are we moving away, not from integration, but from the society which made it a problem in the first place? How deep and at what rate of speed is this process occurring? These are some vital questions to be answered if we are to have a clear sense of our direction.

He then turns his argument toward a particular solution offered by a sociologist. He prefaces this section of his talk by first mentioning African American patriotism:

As I have said time and time again, Negroes still have faith in America. Black people still have faith in a dream that we will all live together as brothers in this country of plenty one day.

But I was distressed when I read in the New York Times of Aug. 31, 1967; that a sociologist from Michigan State University, the outgoing president of the American Sociological Society, stated in San Francisco that Negroes should be given a chance to find an all Negro community in South America: ‘that the valleys of the Andes Mountains would be an ideal place for American Negroes to build a second Israel.’ He further declared that ‘The United States Government should negotiate for a remote but fertile land in Equador, Peru or Bolivia for this relocation.’

I feel that it is rather absurd and appalling that a leading social scientist today would suggest to black people, that after all these years of suffering an exploitation as well as investment in the American dream, that we should turn around and run at this point in history. I say that we will not run! Professor Loomis even compared the relocation task of the Negro to the relocation task of the Jews in Israel. The Jews were made exiles. They did not choose to abandon Europe, they were driven out. Furthermore, Israel has a deep tradition, and Biblical roots for Jews. The Wailing Wall is a good example of these roots. They also had significant financial aid from the United States for the relocation and rebuilding effort. What tradition does the Andes, especially the valley of the Andes Mountains, have for Negroes?

King’s geopolitical and historical synthesis is remarkable, and undoubtedly his theological training helped him to some extent. Here’s the paper that King was referring to. His point is well taken and speaks to the problem of suggesting solutions to social inequality without much connection to the vulnerable communities most affected by those solutions. King concludes with his own take on social science research with a clever use of a widely used psychological concept, “maladjustment.” He first points out what’s so helpful about this term for American society, the need to root out destructive maladjustment. But then he turns this into a sociological issue:

But on the other hand, I am sure that we will recognize that there are some things in our society, some things in our world, to which we should never be adjusted. There are some things concerning which we must always be maladjusted if we are to be people of good will. We must never adjust ourselves to racial discrimination and racial segregation. We must never adjust ourselves to religious bigotry. We must never adjust ourselves to economic conditions that take necessities from the many to give luxuries to the few. We must never adjust ourselves to the madness of militarism, and the self-defeating effects of physical violence.

And he ends with the call for a new organization, the Association for the Advancement of Creative Maladjustment, again invoking the Bible (specifically the Old Testament prophet Amos).

Thus, it may well be that our world is in dire need of a new organization, The International Association for the Advancement of Creative Maladjustment. Men and women should be as maladjusted as the prophet Amos, who in the midst of the injustices of his day, could cry out in words that echo across the centuries, ‘Let justice roll down like waters and righteousness like a mighty stream’; or as maladjusted as Abraham Lincoln, who in the midst of his vacillations finally came to see that this nation could not survive half slave and half free; or as maladjusted as Thomas Jefferson, who in the midst of an age amazingly adjusted to slavery, could scratch across the pages of history, words lifted to cosmic proportions, ‘We hold these truths to be self evident, that all men are created equal. That they are endowed by their creator with certain inalienable rights. And that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.’ And through such creative maladjustment, we may be able to emerge from the bleak and desolate midnight of man’s inhumanity to man, into the bright and glittering daybreak of freedom and justice.

Drawing together sacred scripture with major historical figures of America’s political arena, King masterfully conveyed a picture that is unapologetically American in its creativity, innovation and pragmatism. Knowing his audience, his suggestion of a new association fits well with the assumptions of the social science community: progress is collaborative and relies on cooperation among many minds. But he did so without getting bogged down with jargon, but rather appealed to their civic and religious sensibilities. In doing so I imagine he alienated some, caused others to reflect, and draw praise from others.

It would be interesting to have a conversation over the structure and aims of an AACM today, and a quick search on Google reveals that indeed such an organization exists. What do you think of King’s idea, could we use an Association for the Advancement of Creative Maladjustment? Would we benefit with a collaborative network of scholars who help promote the cause for social justice by revealing the complexities of our ever-increasing societies? If so, what would it look like today?