In the Christmas season when lots of joy and cheer abound, we know that this sentiment is not always shared by those around us. I’m not talking about those who don’t believe in Santa or those who don’t believe in Jesus. I’m talking about those among us who fight the noonday demon called depression. A lot of us who skim this blog already know this: suicide attempts and depression run higher in these winter months and a number of theories have been kicked around to explain what’s going on. For sociologists, suicide and depression are matters of context: people who are disconnected, who feel like they don’t have a community feel especially ill at ease during this time when they feel set apart from those around them that are involved in a group.

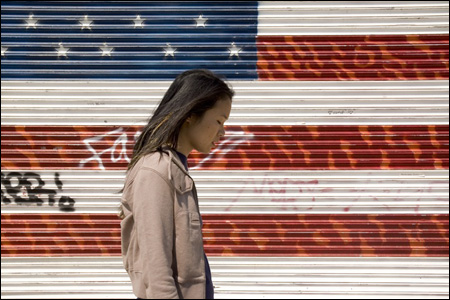

This is of particular importance and interest to me because I discovered that one of my former students, a bright young African American woman, took her life in graduate school, and because I have noticed a few reports recently of well noted young Asian Americans (all Korean I might add) who have also taken their lives in the past few months. What were their lives like that they should feel terminating it was better than getting help? If I sit and think about it too long I can only conclude that sometimes some people will do what they will do regardless of what we may know about their circumstances. But to the extent that we can identify possible patterns of distress and possible solutions for alleviating that distress, social science will remain an important field of study with direct applications for our nation and our local communities.

Readers of this blog also probably know intuitively that Christian churches are one way in which “groupness” can help people fight off the winter blues or however they describe it. Interestingly, the research (of which there is a LOT) is actually mixed on this point. Some studies find that being involved in a church helps people feel integrated; others suggest that the “strictness” of a church (how much it frowns on “bad” behavior) may actually create too much internal tension thus creating or amplifying depression. The studies keep coming in and we’re still not completely clear on what works and what doesn’t.

In a study I stumbled upon recently however caught my research eye. Sociologists Richard Petts and Anne Jolliff examined data on several thousand American adolescents in the mid 1990s. Unlike a number of studies on depression among youth, this one actually included African, Asian, and Latino youth alongside their white peers. This inclusion by itself sets this study apart from the pack, but their findings really push our thinking in important ways. Why? Because while greater church attendance is associated with lower depression among black and white teens, this linear relationship does not appear for Asian and Latino teens.

In a study I stumbled upon recently however caught my research eye. Sociologists Richard Petts and Anne Jolliff examined data on several thousand American adolescents in the mid 1990s. Unlike a number of studies on depression among youth, this one actually included African, Asian, and Latino youth alongside their white peers. This inclusion by itself sets this study apart from the pack, but their findings really push our thinking in important ways. Why? Because while greater church attendance is associated with lower depression among black and white teens, this linear relationship does not appear for Asian and Latino teens.

Before digging a little deeper, allow me to review some basic features about race and depression. Racial minorities typically score higher on depression symptomatology as a result of their minority status. Despite our desire to believe that race doesn’t matter, higher rates of depression suggest otherwise. This difference may be due to a variety of reasons including lower socioeconomic status, family instability, immigrant status and cultural expectations that are at odds with the world that these teens see in their school or through mass media. This can include highly restrictive rules on friendships with non-same-ethnic peers, and prescribed expectations on one’s role in the family (working the family business, narrow aspirations for careers based on monetary gain and perceived high social status). It’s not about genetics, it’s about social conditions that are tied to many minority teen lives.

That said, I want to turn to the researchers’ findings regarding Asian Americans. Petts and Jolliff found the following in their analyses: “…there is evidence that religious participation may be associated with higher depressive symptoms for Asian adolescents.” Further they state: “Indeed supplementary analyses suggests that the positive relationship between religious participation and depression is especially strong for second-generation Asian adolescents.” And a little later they find that “once self-esteem is accounted for, Asian youth are actually more likely to experience lower depression if they feel that religion is unimportant.” To be more clear, no other group of teens, based on race categories, shows this pattern of “more religion, more depression.”

That said, I want to turn to the researchers’ findings regarding Asian Americans. Petts and Jolliff found the following in their analyses: “…there is evidence that religious participation may be associated with higher depressive symptoms for Asian adolescents.” Further they state: “Indeed supplementary analyses suggests that the positive relationship between religious participation and depression is especially strong for second-generation Asian adolescents.” And a little later they find that “once self-esteem is accounted for, Asian youth are actually more likely to experience lower depression if they feel that religion is unimportant.” To be more clear, no other group of teens, based on race categories, shows this pattern of “more religion, more depression.”

Petts and Jolliff explain that perhaps the traditional and patriarchal nature of Asian religious institutions may explain these patterns. Further they suggest that since Asian American youth identify less with Christian religious institutions they face an added tension where their cultural heritage is bundled not only with a culture that they see as “not American” but also a religion that is “not American.” This is sometimes described as having a “double minority status” although it’s usually applied to a combination of racial and gender statuses.

As with many studies, this one too has its limitations. The small number of Asian teens surveyed makes it hard to determine whether it is double minority status or whether Asian American Christians also suffer from the same problem. It appears that Asian American teens who are not religious are actually protected from depressive symptoms. So as I reflect on this season that is supposed to celebrate hope for many Christians, a hope that even compels one to want to tell others about it, I am left wondering whether Asian American Christian communities might actually be killing the hope in their youth? If the suggested explanation, a cultural dissonance at church, is part of the puzzle, what should an Asian American Christian community do? Do they have to give up even more of their ethnic identity in order to preserve the mental and spiritual health of the next generation? Is there another way?