The raising of Lazarus is a very long story, a chapter length tale. And almost all of it is marked by silence.

The raising of Lazarus is a very long story, a chapter length tale. And almost all of it is marked by silence.

In this, the story mirrors our own experiences of the deaths of people we love. We weep, our hearts are broken. We pray No, no , no, no, and, irrationally yet predictably, we talk to the dead in our grief.

We wonder if God, or the Spirit, or whatever is out there, cares.

And God remains silent. And God remains silent.

Our broken hearts go through their anguish, touched at times by what we feel may be God’s care. Or not. And so it goes.

Barbara Brown Taylor remarked twenty years ago in her Beecher Lectures at Yale, that if God would speak up, instead of remaining in silence, the preachers could all retire. So it is in the silence of God that preachers speak to people who are really at sea and in pain.

This was true for Lazarus’ sisters, Mary and Martha. They sent word to Jesus, via his disciples, that Lazarus was dying. And later, that he was dead. And the disciples were astonished by Jesus’ silence, by the turning of his attention elsewhere, though he did say he would attend to this.

We ourselves think of death as urgent, but of course death is the end of urgency.

It is our pain which makes it seem urgent care is needed. But our pain is not going away any time soon. As Jesus knew.

When at last Jesus approached that town, the two sisters rushed out to meet him. The subdued Martha came first, complaining a little about his lateness, but also declaring nothing could be done, he, Jesus, would have had to get there before the death, and that opportunity was now lost.

She spoke as Martha always spoke in the stories we have of her, matter-of-factly and a bit indignantly. With reserve, and with conclusion. Sure in the her knowledge that she was right about the situation. And wanting Jesus to know.

Jesus walks on, toward their town.

And then Mary arrives, falling at his feet, passionately weeping and reproaching him for not having saved her brother. How could he have come too late? Her anguished tears fall upon him, touching his feet literally and smiting his heart spiritually. And Jesus weeps.

And then, in the forty-third verse, Jesus speaks, calling, Lazarus, come out.

And immediately, the sunken Lazarus rises, to that voice and that word.

Most of our reflections are about that rising, that terribly awesome rising.

But perhaps we may discover more if we pay attention to the long silence, and to the spoken word.

It is the habit of God to be mostly silent. Even in the story of the Creation, whole days are filled with the creation responding, in the silence of God, to a precious few spoken words. Rising, rising, to life after a brief, Let there be . . . .

Biblical literary days are long, and many (I, for one) consider them to be eternally ongoing, unended yet. But the words spoken in them by God do not increase. The words remain what they always were – tersely brief biddings.

So it is with Lazarus’ death. A long, perhaps pregnant, silence is observed, in which neither Lazarus nor Jesus speak. A long time of inarticulate sobbing and the usual trite sayings by the grieving. And then a brief few words: Lazarus, come out.

From these stories, and from others, we learn that silence belongs to us, the creatures of this world, the waters and the heavens, in which we are to rise and become life.

The silence of God, then, is our part of the conversation. A conversation in which we respond to the power of the breath and word, by rising into ourselves, into the fullness of our being.

And the words of God, invariably, bid us to rise. To become life. And the words of God are spoken in response to our tears, our deep, deep sorrow.

This is God’s speech. This breath, uttered in a few words responding to sorrow’s tears, no more than a few seconds’ time in long days, bids us to rise.

And so all those other words: curses, rages, refusals, denials; all those other words, are not God’s words. And all those other prompts, our frustration, our anger, our fear, our pain, will not elicit godly words. Only deeply felt tears for another, not for ourselves, will elicit God’s word.

The word of God, for us, is what it always is: Come out. And it is spoken to someone we have given up as lost.

Come out of where you are sunken, and rise.

Jesus will soon do this himself, and in rising, will warn Magdalene not to hold him back from rising, for, he will tell her, he has work to do. And it is not here.

In the midst of all our fancies about heaven, about lives after death, about hell and purgatory, about angels and the devil – and in the midst of our shrinking few thoughts about how awful it must have been for Lazarus to walk about knowing he was going to have to go through death again – in the midst of all this, we really do not know what the work is we rise to do.

No more did the first bird understand the centuries of flying and the countless threats that lay ahead. No more did Adam and Eve know what life east of Eden would be like. No more did the disciples know what the early church could become. No more do we know what our own works will produce.

And yet we rise. And we hear those next few words, Unbind him and let him go.

And this now is our agenda in this world. This is to be our work. In the long silence of God,in all this time we are given in which to do what is needed, our work is to unbind this living world and let it go.

____________________________________________________________________________

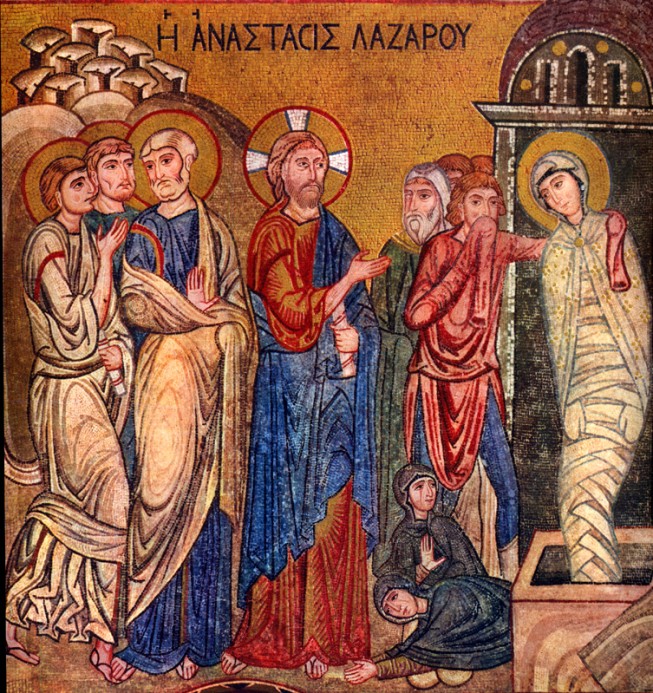

Image: Raising of Lazarus. Mid 12th century. Cappella Palatina di Palermo, Italy. Vanderbilt Divinity School Library, Art in the Christian Tradition.