Here we are, in 2016, and the earth is lit up by warfare fueled by religion. Not by wars exactly, as it was, say, in The Thirty Years War in Europe, nor by armies of Crusaders on the march.

Here we are, in 2016, and the earth is lit up by warfare fueled by religion. Not by wars exactly, as it was, say, in The Thirty Years War in Europe, nor by armies of Crusaders on the march.

But Paris, Brussels, San Bernardino, Istanbul, and (groan) Syria have all been bombed by those whose hatred wears the name of some cruel god. All those bombs fly religious flags. And in an uncountable number of heinous acts, individual women and groups of girls have been burned, mutilated, murdered and cast away for acts considered shameful to the same angry gods.

These large events fill the news, and they fuel endless smaller conflicts on school yards, city streets. Americans know almost nothing about religions beyond their own. And in this age of non-participation, religious knowledge is more folkloric and suspicious than catechetical.

Behind all this beat the bass notes of anti-Semitism, rearing its ugly head with regularity, and the KKK is making a smallish come-back.

Enter Morgan Freeman.

Armed with a large heart, for which he honors his Baptist grandmother in whose home he was raised, and an inquiring mind, which he himself has cultivated for decades, leaving behind the narrow prejudices of his past, Freeman has set himself a world-wide journey of discovery about God, asking questions and listening to the voices of those who offer us the personal answers their religion offers them. And you and I get to come along.

These are not the haters, who have twisted religion into weapons. These are believers, lovers of traditions which teach them tenderly. In an interview with Jon Huckins on Patheos, Freeman said of his new series, The Story of God: “I am a huge proponent of listening to and learning from those who view God and the world differently than I do. For me, I don’t find this threatening to my faith, but enlivening. In fact, I would argue that moving toward those of different faiths doesn’t compromise my faith; it reflects the very best of it.”

The series opened last night (on the National Geographic Channel) with an episode exploring the question, What happens when we die? Freeman tells us that his southern childhood included death, the deaths of his grandmother and of his brother. So he has been wrestling with death for a long time.

Last night he took us to the pyramids of Egypt, into Aztec culture, into a Jerusalem layered with Judaism, Christianity and Islam, sometimes in one building. On a place that used to be an open barrens – Golgotha, once a hanging hill – now stands a cathedral.

Human beings are believers, Freeman says. And in every culture, people draw from their beliefs, meanings about death and an understanding of how to approach it.

The hieroglyphic spells carved within the pyramids of the Pharoahs were prayers that let each Pharoah cross and recross, on a nightly basis, the demon-infested lake of fire between life and eternity. In doing this, the Pharoah ensured for the living that the sun would rise. The Sun God Horus was pleased, and the power that sustains the world and all the people, was made safe.

In a darker ritual, Aztec priests slaughtered sacrificial victims, whose blood, whose very beating hearts, were offered to sustain the living. Anyone’s blood had this power, not just the monarch’s. But the need for bodies was greater. This Day of the Dead ritual has roots as well in Catholic All Saints-All Souls festivals. The power accorded to the dead, that they can sustain the living, is more than Christians alone recognize. There is a fusion of beliefs at work.

Freeman journies on to India, where he engages in learning about Hindu belief in karma and reincarnation, how the way you live determines whether you come back to a good life or a miserable one. And more: that the end goal is to escape resurrection entirely, to enter moksha, which is liberation beyond resurrection.

Christianity, says Freeman, finds in places of death, hope: not merely memory, but hope. And churches – and temples – are places for remembering. And part of what is remembered is how the Divine moves from the ancients to us. Moving back to New York, Freeman learns from modern science that consciousness continues beyond death, at least for a while.

This series will continue for five weeks – and I am eager for them all. I would have watched a second hour yesterday, for there was much that Freeman did not touch, other faiths, other thoughts. But he knows his audience, and knows how thinking about religion, which is compelling for all people, can be very tiring. Perhaps because it touches such deep, abiding questions.

On, then, to a second question: Will there be an End of Days?

_________________________________________________________

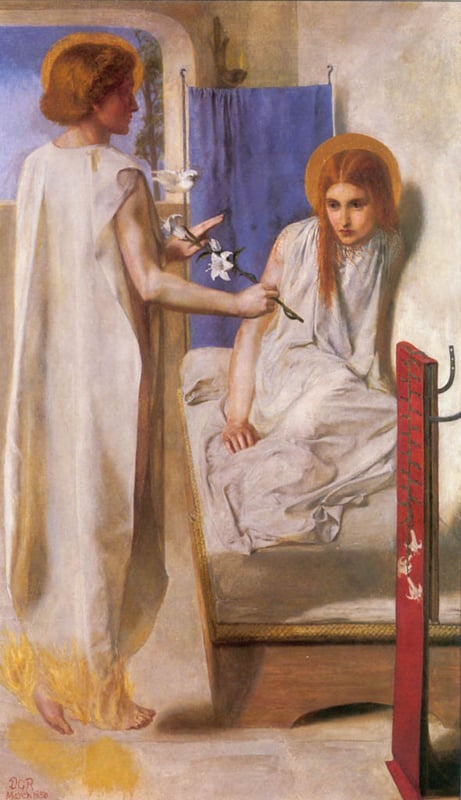

Image of Freeman from National Geographic via Patheos.com, Jon Hickman’s interview with Morgan Freeman.