The Great Law of Judaism, the Law given to Moses by God on Mt. Sinai, the Law written in stone as the Ten Commandments, holds out only one sexual sin: adultery.

The Great Law of Judaism, the Law given to Moses by God on Mt. Sinai, the Law written in stone as the Ten Commandments, holds out only one sexual sin: adultery.

Jesus, in his lifetime, embraces some who have broken each of the Ten Commandments, as a sign of his redeeming work, as a sign of the power of forgiving love, and as a demonstration to us all of what it means to take up his work and follow him.

Perhaps because adultery was so unforgiven in his century, he upholds several adulterous women, and he confronts men who would judge them, warning them to look at their own hearts’ desires.

The Lenten gospel reading for next Sunday is one of these tales. It is the story of the Samaritan woman at the well, the woman who has had five ‘husbands’ and who is now living with a man who is not her husband.

To her Jesus gives the first cup of the water of eternal life. To her. And to be sure we do not mistake his meaning, he names to us the number of men she has taken to her bed, as he makes it clear to her that he is not in ignorance in his sharing, nor is he condemning her in any way. In fact he lifts her, from obscurity, from her Samaritan identity, from social disgrace and marginalization, by his signal, intentional honor.

She receives from his hand this cherished cup. She is the first to receive it. She shall not have to ‘earn’ this gift from another disciple who might speak to her reprovingly, or demand her confession and repentance, before she may drink in eternal life. She is, in fact, the first among equals, and equal to those who received this cup at the Last Supper.

The story is one of the great signs and wonders in John’s gospel. And it is one of the highest tales of Jesus. And it is always read in Lent.

It is astonishing that the Roman Church ignores the meaning of this tale, and says instead that only male disciples are worthy to serve this cup to the world and to themselves. Even in those churches which do ordain women, this woman does not hold her rightful place of honor.

And it is even more astonishing that this cup became foundational in the creation of a human order with only white males at the top, and only white males given recognition as wise and appropriately powerful. A human order, established in both secular and religious Christendom, in which people of color were for centuries allowed to be bought and sold by white men, and women, whether white or of color, had value only as bearers of children and servants of men.

Astonishing because, in this revered story, it is the woman, an adulterous woman, who proclaims to her whole village the wisdom and meaning of this cup and of eternal life. And she brings them the invitation to share in it.

And it is not just her adultery from which the Church has turned away. The virtuous women around Jesus are likewise overlooked. In the raising of Lazarus, it is the tears of his sister Mary, Jesus’ specially welcomed disciple, that awaken in Jesus his own tears and then his power to bring Lazarus back to life.

Jesus’ first Easter greeting is given to Mary Magdalene, who bears the tale back to the men. They don’t believe her, of course, what else is new? But why does the Church dismiss the meaning of her priesthood here?

Jesus’ own mother knew so much better than most of the men who have proclaimed him, what his life was about: the scattering of the proud in the imagination of their hearts, the casting down of the mighty from their thrones, the exalting of those of low degree and filling the hungry with good things, while sending the rich empty away. Yet she is revered not for her wisdom, but for a preposterous claim about her vagina, that she never experienced intercourse, not before and not after Jesus’ birth. She should be famous for her courage, her wisdom. But alas, she is famous only for her vagina.

All this wisdom in, and all this honoring of women by Jesus, has nothing to do with the presence or absence of men in their vaginas or in their lives. And it ought to make the Vatican insist on including women’s voices in their conversations about – well, about everything.

Reading the stories of Jesus ought to make the Vatican see clearly that the vagina has no bearing on the wisdom or the righteousness of any woman.

Nor does living separately as a community of men in any way improve the energy, the wise decision-making, or the understanding of men.

But alas, the Vatican persists in these fallacies and in having all-male conversations, and in making a big deal indeed of the times when it invites a few women in to talk.

The Sanhedrin was an all-male Council, and it ended up murdering Jesus despite the demurrals of a few of the men on it. The weeping women of Jerusalem, however, reached out to him as he made his way up Golgotha, and are remembered because he spoke to them, where he had refused to speak to the Sanhedrin.

Two weeks ago the only woman advisor on the Vatican’s council for abuse victims quit, saying the Vatican resistance to dealing with these issues is unrelenting. And home she went to Ireland, a deeply Catholic country now so alienated by priestly abuse the people flout church sexual teachings in the ballot box. And well they should, for those teachings are ridiculous. All of them. They are all about the vagina. And Jesus was unconcerned with the vagina.

The smug sureness of white men in Christendom, that they alone are meant to rule the world, that they alone know best and understand best, and need to be the leaders of women, is a stain upon the Church.

Even Madison Avenue knows this – the QuickBooks ad, now appearing widely on network TV, featuring Janette, the wedding pastor, knows where the future lies, and where the people’s money will follow, and that the blessing of love can be as well done by people with vaginas as it can by people without them.

For heaven’s sake, people, that’s what Jesus said to the woman at the well – he said You can do it, and he said, I choose you.

____________________________________________________________________________________________________

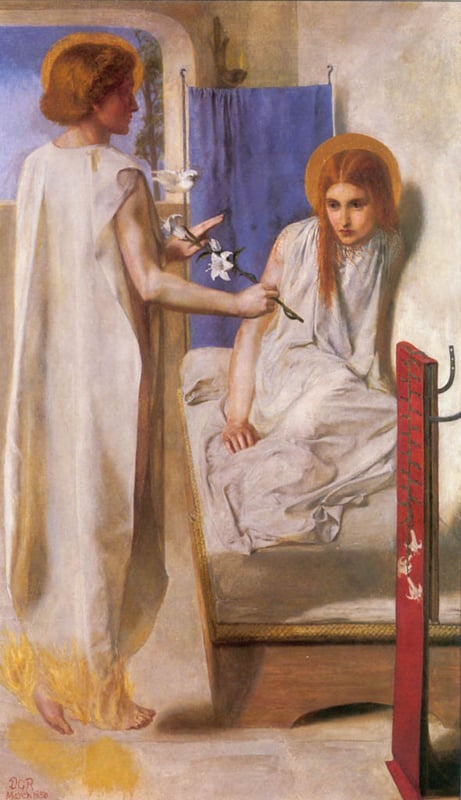

Image: Christ and the Samaritan Woman at the Well, by Julio Romero de Torres, in the Museo de Romero de Torres, Cordoba, Spain. Vanderbilt Divinity School Library, Art in the Christian Tradition.