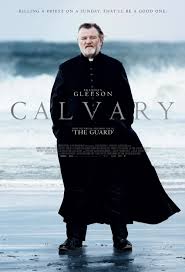

Some things are best saved until later. On the basis of the fine review by my friend Philip Jenkins, I ordered the Irish film ‘Calvary’ from Amazon.UK. This review is here during Advent due to the luck of the draw. Personally, I recommend saving watching this movie until after the New Year. Maybe even wait until Lent or Easter week for full impact. The film, all 98 minutes of it, has been called a classic, and perhaps the best Irish film ever. Certainly, it strikes a nerve, or better a stake at the heart of post-Christian and yet still profoundly Irish Catholic Ireland. What happens to a country when its form of Christianity hangs around its neck like a noose, or at least a huge iron cross, a painful reminder of past misdeeds? What happens when trust turns to rust, and faith degenerates into cynicism, and bitterness, and anger, and the desire for revenge? Maybe the story of Judas tells us something about what happens. Maybe. What I know for sure is that this movie is not a black comedy. It is not a comedy at all. It is tragedy of Greek proportions. It is a Calvary without an Easter…… well, almost. Not quite.

First of all, Brendan Gleeson, Kelly Reilly, Aidan Gillen, Chris O’Dowd and the rest of the cast are spectacular. This becomes all the more evident because the script is brilliant, due to the spot on writing of John Michael McDonaugh who also directs. It is interesting that he insisted that the actors do a verbatim, not vary to the right or the left from the script. And they didn’t. These are the characters Mr. McDonaugh wanted us to see.

Second, the story line follows hard on the heels of all the Catholic pederasty scandals in Ireland and elsewhere and is timely in that respect. There is a scandal at the heart of Christian ministry in general, not just with Catholics but also Protestants and the Orthodox, for there are many tales that could be told of the abuse of ministerial power to gain sexual pleasure from someone— be it a child or an adult, a male or a female, a married or a single person. Of course in Catholicism part of the problem is the requirement of celibacy, and one can only hope something will be done about this by Pope Francis. Many good persons who are called to be Catholic priests, or believe they are, are not called to celibacy and shouldn’t be expected to meet such a requirement. This change would certainly have prevented a lot of sexual abuse by Catholic clergy along the way. But I digress from the film, for the film both is, and is not about a bad priest who abused someone sexually for years, in this case, a young boy.

It is about that subject because there is a grown man in the film who comes one day to the confessional, and not only related that he had been abused by a priest for five years as a boy, and that that priest was long since dead, but in the confessional he told the current priest he intended to kill him, to kill a good priest who was not a abuser, presumably as an act of revenge. The story thereafter becomes a whodunnit, because we are not party to the information as to which of the male adult townfolk came and made this confession. Indeed, the reveal only comes at the very end of the film.

At the heart of the film is an interesting series of dialogues between the good priest and a variety of persons about living a good life, indeed a Christ-like life. At one juncture the priest tells a young man who is thinking of joining the Army to learn a trade that this is flatly against the command ‘though shalt not kill’ and he adds, and there is not an asterisk beside this command giving a list of exceptions. He is right about that. There are many such deep and probing exchanges, dealing with what is and is not a moral act, a human and humane act, a Christian act, in this film. Exchanges between the priest and his superior, the priest and his friends in the pub, and most importantly the priest and his daughter. This priest had been previously married, and after his wife died, he had felt called to the priesthood, but his daughter felt this as an abandonment of her. Some of the most moving scenes in the movie are between Gleeson and Reilly as father and daughter working on reconciliation and forgiveness.

Yes forgiveness turns out to be the heart of the matter. At one juncture we see a quote from St. Augustine which says in essence ‘Do not despair, one of the thieves on the cross was saved at the last moment. Do not presume, one of the thieves on the cross spent eternity in hell’.

There is so much to ponder in this film, that I shall watch it several more times. When I can bear to do so. But you lot….. you all need to see it, only wait until after Christmas. Otherwise, it will spoil your eggnog…..

What makes for an excellent movie are many things, and most of the time it requires an excellent script enacted by excellent actors, something apparently totally lost on the Hollywood producers of late.