[The following is a response to Adam Hamilton’s recent blog post and forthcoming book on the issue of how to approach Scripture, by my colleague and friend Bill Arnold. I am entirely in agreement with Bill on the flaws in Hamiliton’s approach and argument and am happy to post this response here, now. BW3]

——-

Adam Hamilton’s Buckets Don’t Hold Water

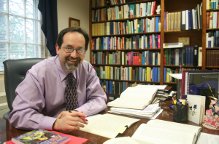

By guest blogger Bill T. Arnold

Things just got even more interesting for United Methodists. A bishop in New York has called for a cessation of church trials for pastors who celebrate same-gender wedding ceremonies even though such ceremonies violate the church’s Book of Discipline (here [hypertext: http://www.nyac.com/newsdetail/96157]). In response, one of the church’s leading pastors, Rev. Adam Hamilton, suggested here [hypertext: http://www.adamhamilton.org/blog/view/151/homosexuality-the-bible-and-the-united-methodist-church#.UyL1_L-2MmU] we should think of Scripture as falling into three “buckets.”

1. Scriptures that express God’s heart, character and timeless will for human beings.

2. Scriptures that expressed God’s will in a particular time, but are no longer binding.

3. Scriptures that never fully expressed the heart, character or will of God.

Adam asserts that the third bucket is disconcerting for some, but insists that either way, we have to put the hard-to-read bits into at least one of the first two buckets. He then asks this question. “Whether you believe in two buckets or three, the question remains, Which bucket do the five passages of scripture that reference same-sex intimacy fall into?”

My response is simple. These buckets don’t hold water! None of us should take up this call to divide Scripture into three buckets. Please, let us not consider dividing Scripture into separate texts that belong in any of these buckets. I reject the idea that certain portions of Scripture about sexual ethics fit into one bucket while others fit into a different bucket.

Why is this a bad idea? For several reasons, beginning with the fact that Adam’s categories – the “buckets” – are extraneously imposed upon the canon of Scripture. The Bible’s self-claims rule it out of order (beginning with 2 Timothy 3:16-17). This is a foreign concept, imposed upon the flow of the canon and the whole tenor of Scripture.

Beyond this simple reminder that “all scripture is inspired by God,” we need also to remind ourselves that we United Methodists view the Bible “as sacred canon for Christian people,” specifically the “thirty-nine books of the Old Testament and the twenty-seven books of the New Testament” (2012 Book of Discipline, ¶105, page 82). When we join a local UM congregation, we proclaim that we “receive and profess the Christian faith as contained in the Scriptures of the Old and New Testaments.” At ordination, we proclaim publicly that we are persuaded the Scriptures of the Old and New Testaments contain all things necessary for salvation through faith in Jesus, and that those Scriptures “are the unique and authoritative standard for the church’s faith and life.”

As sacred canon (or authoritative standard) for the church, we believe the Bible is not primarily inspired for us to know things (epistemology). We learn quite a lot from the Bible, of course. But this is not its primary function in and for the church. Instead, the Bible is inspired and given by God to the church in order for Christians to know God through personal and corporate salvation (soteriology). Even my use of the word “know” in the previous sentences has different meanings. By “know” when referring to things, I’m essentially referring to the use of our brains to accumulate facts. But by “know” when referring to God, I mean encountering God and relating to God in a way made possible by the atonement of Christ on the cross. We believe the whole canon is a gift from God, inspired to lead us to an intimate relationship with God individually and corporately, and to transform us into God’s image.

We simply cannot decide which portions fail to express God’s will. That’s not our job. And that’s good, because we’re not capable of deciding which bits aren’t reflecting God. In a word, the Scriptures are God’s word for us, not God’s command to us. As Bishop Scott Jones has said, a Methodist way of reading Scripture seeks “the whole message of the Bible, listening carefully to its individual parts but also seeking to understand the entire book as concerning the saving activity of God, reconciling humanity to himself and restoring them to the image in which they were created” (Scott J. Jones, John Wesley’s Conception and Use of Scripture [Nashville, Tenn.: Kingswood Books, 1995], 223).

In our interpretive tradition as Wesleyans, we do not elevate one portion or sub-portion of the Bible as more authoritative than others. There is a definite progression or gradual revealing of God and God’s message in the Bible. But we do not believe that later stages of revelation necessarily replace, dismiss, or nullify earlier stages of revelation (known as supersessionism). When we dismiss any portion of Scripture as outside the character, will, or heart of God for any reason, we have essentially turned Scripture into a historical witness about God, not a revelation from God. What is perceived as today’s superior wisdom trumps or supersedes the wisdom of the church’s Scriptures. The Bible becomes nothing more than a witness to God, not a revelation of God.

Rather than simply dismissing the hard passages we cannot understand or cannot agree with, it is our task as Christians to keep reading them for deeper understanding, praying along the way that the texts transform us through the ministry of the Holy Spirit. Deciding that certain ones don’t express “the heart, character or will of God” turns everything around backwards. We’re creating a Bible in our own image.

Besides, what are we supposed to do with those texts we’ve decided don’t express the will of God? Should we cut them out of the canon of Scripture? It’s not that I think the third bucket is “disconcerting,” I find all three troubling as a serious proposal for reading Scripture.

So, what is the nature of divine Revelation? What is the nature of the church’s Scripture? When we embrace the entire canon, both Old and New Testaments in their entirety, we acknowledge that God has revealed and is revealing Himself through these writings. And that includes the hard bits we may not like or completely understand. The task as Christians is to pour ourselves into the difficult job of understanding them better, and praying the Holy Spirit will use them to transform our lives. Anything less is a sub-Christian way of reading the Bible.

For more on reading Scripture as Methodists, see pages 70-89 in Bill T. Arnold, Seeing Black and White in a Gray World: The Need for Theological Reasoning in the Church’s Debate over Sexuality (Franklin, Tenn.: Seedbed Publisher, 2014).

Bill T. Arnold, Ph.D.

Paul S. Amos Professor of Old Testament Interpretation

Asbury Theological Seminary

204 North Lexington Avenue, Wilmore, KY 40390-1199, USA

———