All objectification tends towards murder, all self-objectification to suicide, for the only time a person is only an object is when he is a corpse.

Alive and kicking, on the other hand, the person is a synthesis of subjectivity and objectivity. If this vocabulary is unfamiliar, fear not. Your objectivity is simply your outward splay of characteristics, observable-you, and your subjectivity is that unobservable interior life glimpsed through your objectivity, through your physical characteristics, words and outward expressions.

Thus we might say that a man is in despair, drowned in an awful state of being we can never fully know, a state we can only glimpse through his objective expressions of that subjective despair — his moans, his morose air, his incessant scratching and his newfound love for the show How I Met Your Mother. His subjectivity — his unique, first-person experience of existence — radiates outwards through his objectivity, and thus he may communicate himself to others. But we were speaking of dead bodies.

The corpse is absurd. The corpse is an observable body refusing to express an unobservable center. It is a mismatch, as if clear, descriptive language gave way to words without meaning. The corpse gives us a face that is an expression of nothing. The skeleton grins with teeth that are not — despite appearances — an objective display of a subjective happiness, but an objective display of the absence of anything to display. The corpse is an outside that expresses no inside. In short, it is objectivity without subjectivity.

When it comes to corpses, it is not the apparent absence of the person that freaks — for the person is as absent in the rock or the tree as in the corpse — no, it is the pretend-presence of the person, the inescapable sense that the body ought to express an interior subjectivity, indeed, that it looks as if it does express the same — but we know it does not. The natural repulsion we feel towards the dead body seems to me a particular manifestation of the repulsion we feel towards a lie.

But we are here to discuss photography. If the objectified person is a corpse, it would seem that photographers are murderers, for their shootings are a reduction of the person to his objectivity, and the person shot falls into a group of observable characteristics printed on paper — physical characteristics expressed at the moment of the shooting that do not refer back to an actual subjectivity any more than the fixated face of death at a funeral refers back to an actual subjectivity of the coffined. I exaggerate, but only to deliver the core of an argument: We need to take photography seriously. Instagram needs to go to hell and burn forever in undying, filterless flames. The expansion of photographic capacity to every human being with a cell phone has shifted human existence into a sphere in which absolutely everything and anything may be captured, altered and publicized, and thus every human being walking downtown today has the capacity to, at any moment and at the whim of any friend, be reduced to an object, and this reduction — though nothing bad in itself — is a serious business.

Now I believe strange things. I believe that our newfound capacity for publishing daily pictures of our banal existence is not simply the result of newfound technology. It is the result of our desire to exist as objects. That we have a will to self-objectification is not a novel idea, and I will not expound upon it here. (Surely it is enough to point out that objectivity is easy, and subjectivity gut-wrenchingly difficult, that it is easier to exist as an object, as a conglomerate of outer characteristics — as a combination of fashion, career, wealth, relationship status, ideological position — than to exist subjectively, as the self that you are and none other? Surely we can see how concerned we are with our selves as the-thing-observed, and how little with our selves as the unobserved, incommunicable existence that we have to deal with alone in our rooms? Surely we are not fooled into thinking that our modern increase in pornography, reality TV, selfies, social media profiles, political labels, and all other forms of objectification are an accident?)

Because our age is essentially one of self-objectification, our response to photography is to aid the camera in the task of objectification. To put it another way, we have found the obvious truth, that photo is a reduction of the person to an object, and have fallen in love with the photo as such, as a simple method of becoming an object, an object we may upload onto the Internet to be “liked.” Which leads me to the real reason I began my meditation with corpse-thought.

The Duck-face.

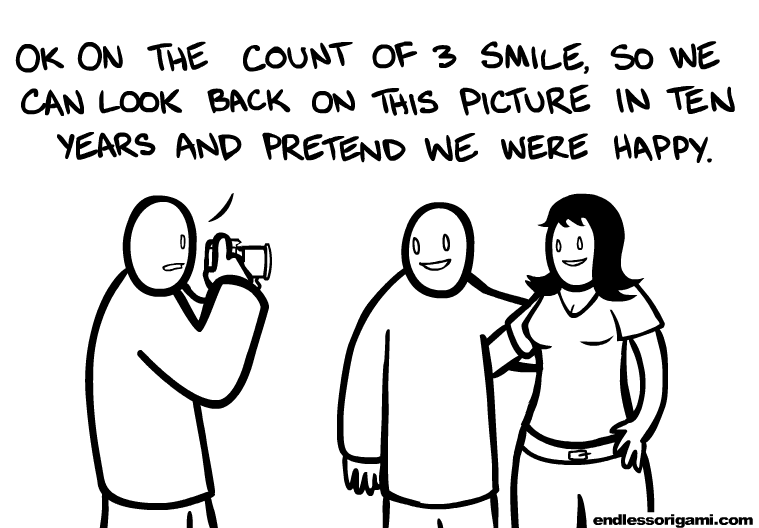

The duck-face is a pose. But what is a pose? A pose is fundamentally a falsehood, and thus I might say “his gestures of affection were a pose,” that is, a lie. In reference to photography, we may say that a pose is a bodily falsehood, an outward assembly of objective characteristics — of gestures, smiles, body language, etc. — that bear no necessary reference to our actual subjective state. A pose, then, is our natural response to the unnaturalness of the camera click, for if we are to undergo the minor death of becoming a photograph — that is, a group of objective, physical characteristics cut off from our subjectivity which expresses itself through these characteristics — it is only appropriate that we sever ourselves from our subjectivity.

This seems evident in the fact that the pose has changed over time. Old photography had the photographed sit without expression. Besides an obvious arrangement of bodies to fit the camera’s frame, there was little effort to manufacture a bodily falsehood for the camera.

It is adorable in its own way, and I hope I am not the only one that sees in the faces of old photos a delightful ignorance of the camera. When the camera was still something of a novelty, when the world was not saturated with objectification and no one could conceive of a family photo being made instantly available to a “liking,” “sharing,” faceless public, or, to put it in the vocabulary we have been using, before people were intensely aware that the camera was about to objectify them, there seemed to be less of a need to aid the camera in its task, less of a desire to create a bodily falsehood for the camera, less of a desire to separate our objectivity from our subjectivity, that the camera, which only delivers objectivity, may deliver us in truth.

The blissful ignorance could not last. Photography increased its output, and people began to pose, to smile for the camera, to the point that, were we now to take a stone-faced family photo, it could only be viewed humorously, ironically, as a mockery of past generations or as a rare moment of familial wit. The need for a pose has become the norm. We know acutely what cameras do, and we act accordingly — “Here comes the object-producer, everyone, on the count of three, separate your objectivity from your subjectivity!”

But even the smile, the thumbs-up, even the standard set of poses everyone assumes as the proper, ethical response to having a camera waved in front of your nose — even these are not enough for an essentially objectified age. What is needed is the duck-face.

Now the duck-face is a unique and hallowed expression of the human person for the simple reason that it, like the face of the corpse, expresses nothing. The man smiling for the camera is posing, yes, but a smile — even a manufactured smile — still allows the observer to glean a glimpse of a potential subjective state — he is smiling, and smiles spring from happiness, and therefore he is happy, or at least pretending to be. The illusion of contact with the interior life of the photographed person has a grounding in reality — we really do smile when we are happy.

The duck-face, however, has no correlative subjective state which it conveys. Were I to give account of the meaning of the duck-face, I could only say, after much contorted effort, that it is a largely female camera-face, a face that seems a near biological response evoked by holding a camera in front of a group of high-schoolers, an expression that only exists in relation to the existence of cameras. So accustomed are we to the selfie that we have forgotten a simple truth — no one makes that face in real life. What emotion, what intellectual epiphany, what situation, what need to the communicate the subjective self through the objective characteristics could possibly result in the imitation of a duck? (At best, the face has some genesis in an expression of sassiness, in a kiss, in a vague sensuality and the movie Zoolander, but if this is true, it has long sense mutated into a face established for the sole purpose of a photograph.) The duck-face makes out of the photograph a self-contained world. It is a camera-face for cameras. By it we exist as the photograph about to be taken.

The difference between sitting still in the 1800’s and baring our lips at an iPhone in 2013 is that, as far as I can tell, sitting still did not display any great will to objectification. The family photographed above are simply being for the camera, sitting politely and looking ahead, as if confident that the camera will deliver them as they are. The duck-face, on the other hand, displays an immense will to objectification, contorting itself into objective state without relation to actual subjectivity and delivering itself to the Internet as such, and this goes for the tongue-sticking-out-to-the-side-winking-grimace thing and any other solely-for-cameras face. The duck-face satisfies a desire for objectification. By it, we become objects apart from subjectivity, for a device that objectifies us, to be delivered unto a world in which all is objectivity cut from subjectivity — the Internet.

Many apologies if that was all too speculative. Until next time.

Postscript: Notes Towards A Possible Way Out

- The problem with popular photography is not that it makes a relation to the person photographed difficult, but that it professes to make it easy, when relation to another person is the most difficult, terrifying task in the universe.

- We say, flicking through profile pictures, that we are looking at a picture of a person, but a person is not observed, a person is encountered through an objectivity that leads to a subjectivity. We are looking at pixels.

- A photograph may certainly evoke our memory and our relation to a particular person, but this is the human mind working beyond the photograph. In itself, a photograph presents the opportunity for observation, but, and as mentioned, the person is not known through observation. He is encountered.

- Faced with this inadequate presentation of ourselves, we have one of two options. We may ourselves become an inadequate presentation of our person, by making a duck-face, squatting absurdly, taking off our shirts, or whatever. Or we may admit that we are not encountered through the selfie — that we may be recognized, sure, as a tree is recognized through a photograph of a tree, but that the photograph provides no road leading to an encounter with our subjectivity.

- If we admit this, the task of true photography becomes one of obscurity, of making our recognition of the person difficult, so as to force the observer to actively struggle to move beyond the photograph.

- What’s needed is inaccuracy.

- What’s needed is unclarity.

- What’s needed is art.