Pope Francis’s Evangelical Critics

Twenty years ago, when Pope John Paul II died, American evangelicals mourned his passing as though they had lost one of their staunchest allies and most beloved friends. John Paul II was “the most influential voice for morality and peace in the world during the last 100 years,” Billy Graham declared in 2005.

Today’s reactions to Pope Francis’s death from conservative American evangelicals are a real contrast to that sentiment. The Gospel Coalition (TGC) published a reflection that accused Francis of promoting a “liquid” Catholicism that prized “vibes over doctrine” and that made the church “less Roman, but no more biblical.” Francis gave less emphasis to abortion and more to progressive causes such as the environment, TGC complained. And he opened ecumenical outreach to Muslims and non-Christians.

Such critiques echoed those of some of the most conservative culture warriors within the Catholic Church. During Francis’s lifetime, Cardinal Richard Burke, the former archbishop of St. Louis, complained that under Francis’s leadership, “the Church is like a ship without a rudder.” “One gets the impression, or it’s interpreted this way in the media, that he thinks we’re talking too much about abortion, too much about the integrity of marriage as between one man and one woman,” Burke said. “But we can never talk enough about that.”

Francis was not necessarily the thoroughgoing progressive that his conservative critics imagined him to be. Contrary to their charges, he actually did not mince words when denouncing abortion. “Abortion is murder,” he declared, reiterating church teaching.

But at the same time, Francis’s critics were right to believe that he wanted to move the church away from the culture wars that had given rise to the alliance between American Catholics and evangelical Protestants in the late twentieth century. Francis sought to reorient the church in the culture war debates – and in doing so, he attracted strong criticism not merely from conservative Catholics but also from conservative evangelicals who may have partly misunderstood what he was doing, but who understood enough to know that Francis’s approach was sharply at odds with what had attracted them to John Paul II a few decades earlier.

Conservative Evangelicals’ Attraction to John Paul II

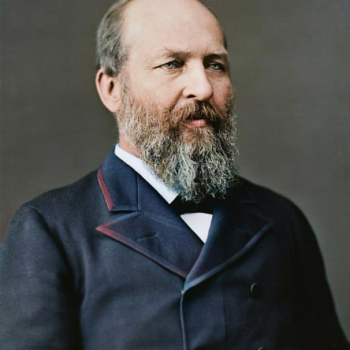

The close American evangelical alliance with conservative Catholics in the culture wars began in earnest during the papacy of John Paul II (1978-2005). There were some tentative alliances between Catholics and evangelicals during the fight against the Equal Rights Amendment in the early 1970s, and a few evangelicals were also borrowing arguments from Catholic pro-life thought before John Paul II became pope, but there was no systematic alliance between evangelicals and Catholics before John Paul II. Yet by the time of John Paul II’s death, evangelicals were freely quoting from his encyclicals and lauding conservative Catholics as fellow believers.

“Evangelicals and Catholics Together,” which Richard John Neuhaus, Charles Colson, and other leading American evangelicals and Catholics spearheaded in 1994, was a product of this culture-war alliance, where evangelicals and Catholics promised to work together for the cause of defending human life and the sanctity of marriage. So was First Things magazine, which Neuhaus founded as a Catholic ecumenical effort in 1990.

Unchanging Values of Human Life

Evangelicals correctly recognized shared values in both John Paul II and Benedict XVI, because both of them saw secularism as the greatest enemy facing the church, and both of them saw a defense of unborn human life and traditional views of marriage and sexuality as the pillars of a strong defense against secularism, just as evangelicals in the United States did.

As late twentieth-century Europeans, John Paul II and Benedict XVI were products of a culture that was very familiar to many American conservative evangelical culture warriors – a world in which Christian values seemed to be under assault from atheism and from state assaults on the family. Whether those state assaults came from communist governments (as John Paul II personally experienced as a priest in Poland) or from liberal secular democracies, the church’s response must be the same: It must champion a set of unchanging values of human life, marriage, and the family, while communicating those teachings in a winsome manner to win the adherence of a younger generation.

Inseparably Connected

John Paul II was a master of this communication style. On his first papal visit to the United States in 1979, young Catholics treated him as a rock star, with tens of thousands flocking to hear his outdoor homilies. In front of those massive crowds, the pope spoke about the value of traditional marriage and the need to defend the unborn. He spoke against homosexuality and all sex outside marriage. And he devoted an unprecedented amount of papal attention to gender roles, giving a series of 129 theologically detailed addresses on “The Theology of the Body” over a five-year period.

Evangelicals who had eagerly received Francis Schaeffer’s cultural warnings in the late 1970s sensed a parallel framework in John Paul II’s homilies and encyclicals in the 1980s and 1990s. Schaeffer may have taken a dim view of Catholicism, and John Paul II may have appealed to theological sources that were unfamiliar to most American evangelicals, but the values and worldviews were strikingly similar. Like many conservative American evangelical writings of the time, the writings of John Paul II and Benedict XVI were grounded by a quest for a timeless, unchanging standard of authority, and an attempt to apply that authority to issues of sexuality and human life, which they thought were inseparably connected.

Conservative American evangelicals may have known that John Paul II did not share their support for capital punishment, nuclear arms buildup, or unfettered capitalism, but those were not first-order issues for them. They were sure that they could count on the Catholic Church to maintain an uncompromising stand on issues of doctrine, especially when it came to human life and sexuality, and that was sufficient. Above all, John Paul II’s moral clarity gave them the confidence they needed to view the Catholic Church as a staunch defender of unchanging truth. Even in the areas where they disagreed with John Paul II and thought he might have misinterpreted scripture, they respected his moral reasoning and his convictions, and they were sure that he was attempting to preserve a consistent standard of morally authoritative teachings. That’s why they were so dismayed by Francis’s papacy, because they thought that he threatened John Paul II’s legacy, both in its conclusions and in its moral reasoning.

Pope Francis’s Repudiation of the Culture Wars

In 2013, when Jorge Bergoglio was selected to become Pope Francis, the Catholic Church was in crisis. The sex abuse crisis had become a global scandal. Catholics were rapidly leaving the church. In Europe and North America, some were leaving Christianity altogether; in Latin America, many were becoming Pentecostals. If the church’s greatest challenge in 1978 (when John Paul II’s papacy began) seemed to be external, the church’s greatest threat in 2013 seemed to be from within. The cardinals wanted a skilled administrator who could address the sex abuse crisis and rehabilitate the church’s image. For that task, they selected the first pope from Latin America.

Both John Paul II and Benedict XVI had believed that Christian witness to the world depended on the maintenance of traditional doctrines about the family – which is why they devoted enormous effort to the definition of doctrine. Like American evangelicals, their views on cultural matters were shaped by the particular experience of the postwar West and its battles with communism, secularism, and the sexual revolution.

Francis, by contrast, was shaped by the Latin American experience of Western imperialism and the exploitation of the poor. When he became pope, he was far less interested in fighting against the sexual revolution or secularization than he was in calling the privileged to show concern for the poor and for the earth itself.

Consistent Life Ethic

The effectiveness of Christian witness to the world, he believed, depended on showing love to others. This was the essence of what Jesus taught. The culture wars were incompatible with this witness, he decided. Instead of writing defenses of Christianity, as his predecessors had, he engaged in ecumenical outreach to non-Christian religions. And instead of attempting to further doctrinally define sexual sins, as John Paul II had, Francis opened the sacraments to those whom the church had said were in sexual sin.

The church needed to maintain its strong opposition to abortion, Francis believed, but instead of linking that opposition to a larger campaign for marriage and sexual conservatism (as American evangelicals wanted, and as John Paul II had done), he instead insisted that it had to be connected to a consistent life ethic. “This defence of unborn life is closely linked to the defence of each and every other human right,” Francis wrote in his first papal encyclical, Evangelii Gaudium (2013). “It involves the conviction that a human being is always sacred and inviolable, in any situation and at every stage of development. Human beings are ends in themselves and never a means of resolving other problems. Once this conviction disappears, so do solid and lasting foundations for the defence of human rights.”

This was not a new message; Catholics (including John Paul II) had said this for decades. Indeed, the consistent life ethic had been the dominant framework that American bishops had employed for their pro-life activism in the early 1980s, before the conservative culture war framework linked to issues of marriage and sexuality became more common among the bishops that John Paul II appointed.

Attack On The Inviolability and Dignity

The consistent life ethic had never gone away, and in fact, even John Paul II and Benedict XVI had shared it, to some extent. Both opposed capital punishment. Francis was not, therefore, breaking new ground in this area or backing away from the church’s fight against abortion. But American evangelicals were correct to see a change in emphasis. For Francis, opposition to abortion should lead naturally to concerns about climate change. “Since everything is interrelated, concern for the protection of nature is also incompatible with the justification of abortion,” he wrote in Laudato Si (2015), his encyclical on environmental stewardship.

In keeping with this idea, Francis strengthened the church’s opposition to capital punishment. This was the one change he made to the catechism – a change to paragraph 2267, which covers the death penalty. Instead of merely saying that the need for the death penalty was “very rare, if not practically non-existent,” the catechism now said that the death penalty was “inadmissible” and that it was “an attack on the inviolability and dignity of the human person.”

Defining Doctrine

If Francis had merely been left-leaning on such issues as climate change, capital punishment, economics, and immigration, the conservatives who had lauded John Paul II might not have objected, because John Paul II (and Catholic bishops of the 1980s) took left-leaning positions on most of these issues. It was not so much what he said in his encyclicals that bothered them; it was what he left out.

One of the things that he left out was the precise moral reasoning and doctrinal precision that had defined John Paul II and Benedict XVI’s official statements and that had bolstered conservatives’ confidence in their abilities to be reliable interpreters of an unchanging moral and theological tradition. Francis viewed doctrine in much more flexible terms than his immediate predecessors did; Christian ethics and sacraments mattered far more than precise doctrinal formulations or the defense of Christian civilization. Even if he himself was willing to go only so far in defining doctrine, he seemed to give permission to others to cross the line that he only hinted at. And the points on which he seemed most willing to allow others to redefine their moral understanding focused on the family and sexuality – the very areas where John Paul II had been most emphatic.

The Spirit Guides Us

“Not all discussions of doctrinal, moral or pastoral issues need to be settled by interventions of the magisterium,” he stated in a 2016 encyclical on love in the family that created an uproar among some conservative Catholics because it allowed Catholics who had been divorced and remarried without seeking an annulment for their first marriage to receive communion. “Unity of teaching and practice is certainly necessary in the Church, but this does not preclude various ways of interpreting some aspects of that teaching or drawing certain consequences from it. This will always be the case as the Spirit guides us towards the entire truth (cf. Jn 16:13), until he leads us fully into the mystery of Christ and enables us to see all things as he does. Each country or region, moreover, can seek solutions better suited to its culture and sensitive to its traditions and local needs.”

Francis seemed to envision the church as a group of people who were trying, however imperfectly, to live out Jesus’s teachings of love for others and who would be willing to give each other the benefit of the doubt. Sacraments, he thought, should be used to make God’s grace available to the maximum number of people, not as instruments of discipline in the culture wars. That is why he opposed the attempts of some American bishops to deny communion to politicians who supported abortion rights.

A Demanding Ideal

And the culture wars needed to be radically scaled back, he suggested. “We have often been on the defensive, wasting pastoral energy on denouncing a decadent world without being proactive in proposing ways of finding true happiness,” he wrote in 2016. “Many people feel that the Church’s message on marriage and the family does not clearly reflect the preaching and attitudes of Jesus, who set forth a demanding ideal yet never failed to show compassion and closeness to the frailty of individuals like the Samaritan woman or the woman caught in adultery.”

Without redefining church doctrine on sexuality, Francis deemphasized it, urging people to show compassion rather than judgment. In the first months of his papacy, he made headlines by saying, “If someone is gay and he searches for the Lord and has good will, who am I to judge?”

Yet when it came to the treatment of immigrants, he showed a holy anger, because this was a first-order moral issue for him. “A person who thinks only about building walls, wherever they may be, and not building bridges, is not Christian,” he said in 2016, when asked about Donald Trump’s immigration policy proposals. “This is not the gospel.”

Defenses of Immigrants

Francis’s episcopal appointments made the American bishops a little less like the culture warriors they were only a few years ago and more like the consistent life ethic advocates that they were in the early 1980s. They are still as strongly opposed to abortion as ever, but they have also been further emboldened to continue defending the rights of immigrants.

I suspect, though, that Francis would have had a greater impact on theological conservatives in the church if he had spoken more clearly about an unchanging source of theological and moral authority when issuing his defenses of immigrants’ rights or his exhortations on climate change – which I think he easily could have done. If he had coupled his statements about the poor with defenses of the family and a traditional sexual ethic, he might have won over more cultural conservatives to his side.

As it is, though, there are signs that a significant wing of the American Catholic Church is moving away from Pope Francis’s framework, because they don’t view it as intellectually cohesive or as the unchanging source of moral authority that they’re seeking. Pope Francis was overwhelmingly popular among progressive Catholics.

The Pope’s Progressive Tendencies

But the youngest cohort of American priests – those ordained in the last decade – are more theologically, politically, and culturally conservative than any cohort of priests ordained since the early 1960s. Even as Francis attempted to push the global Catholic Church away from the culture wars – and even as he elevated American bishops that were less likely to be culture warriors – conservative Catholicism continued to flourish among regular churchgoers, younger priests, and the students who attended some of the most conservative Catholic colleges. Like conservative evangelicals, these conservative Catholics were looking for a countercultural, unchanging authority that could challenge the secularism and sexual permissiveness of the prevailing Western culture. Many of them found themselves at odds with Francis on certain questions, even if Francis didn’t directly change church doctrine.

Conservative evangelicals who wanted to continue their alliances with conservative Catholics thus did so without interruption during Francis’s papacy, and they joined with conservative Catholics in complaining about the pope’s progressive tendencies. Even if most of the progressive political views that Francis held could be found in at least some form in John Paul II’s writings as well, his statements suggested that he didn’t see as much value as John Paul II had in defending traditional Christian teachings on marriage and sexuality, and that he didn’t want to present church doctrine to the world as a bulwark of unchanging truth in a world of uncertainty in the same way that John Paul II did. Conservative evangelicals wanted a beacon of truth – and Francis seemed not to provide it, at least on the issues they most cared about.

Willing to Continue This Alliance

In taking his moral cues from the example of Jesus rather than from natural law principles or church doctrine, as John Paul II had, Francis seemed to think much more like a theological liberal than a conservative evangelical. John Paul II had (like Francis) leaned to the left on economic questions and on issues of immigration and capital punishment, but he insisted on an unchanging moral authority, while Francis did not do so quite as clearly. This is what TGC meant when they complained that he offered a “liquid” Catholicism rather than something solid. It would never work for the culture wars.

Had it been up to Francis, I suspect that the Catholic alliance with conservative evangelicals in the culture wars would have largely come to an end. But in fact, Francis’s influence on the Catholic Church in the United States was limited, and there were plenty of American conservative Catholics who were willing to continue this alliance, with or without the pope’s blessing.

Where Will the Catholic-Evangelical Alliance Go from Here?

It’s impossible to fully predict the direction of papal views of the culture wars. In the 1960s, Pope John XXIII – the last progressive pope who was most comparable to Francis – was succeeded by the more conservative Paul VI, who used an encyclical to reaffirm church prohibitions on most forms of birth control. Pope Benedict XVI – widely viewed as a strong conservative – was succeeded by Francis. The cultural direction of the papacy does not move inexorably in a single direction. The next pope might well be more conservative in some respects – or perhaps not.

Some church doctrines will never change, because they are based on unchanging principles and declarations. Abortion will never be declared permissible, for instance.

The framework for presenting those teachings may change. Through a change in emphasis rather than doctrine, Francis attempted to modify the framework in which the church presented its pro-life teaching, and he received pushback from conservatives both inside and outside of the church.

Culture War Politics

But because Francis (unlike John Paul II) did not redefine the doctrines themselves, it will not be theologically difficult for a future pope (perhaps even the next one) to move the church back toward a more conservative culture-war stance. Reviving cultural conservatism in the church may be as simple as talking more about sexuality and marriage, as John Paul II and Benedict XVI did.

And regardless of whether the next pope does this, it’s easy to see how conservative Catholics could continue doing so, perhaps simply by continuing to re-read John Paul II’s encyclicals and using them as a guide. And if this is the case, it means that the alliance between conservative evangelicals and conservative Catholics that developed during John Paul II’s papacy will continue, no matter how the upcoming papal election turns out.

Pope Francis may have challenged the alliance, but he didn’t have enough influence on conservative American Catholics to temper the culture wars. He will be remembered as a pope who attempted to change the church’s tone in public life, but in the United States, the joint efforts of conservative evangelicals and conservative Catholics kept alive an alternative approach that undermined Francis’s vision and prevented it from ever becoming a full reality. At least in the United States, the legacy of John Paul II will probably overshadow Francis’s for the foreseeable future, especially when it comes to culture war politics.