At special times of the year such as Easter, I always like to offer seasonally appropriate posts. That is what I will be doing again this year, but if the season is suitable, the topic is… maybe not so much. In fact, I want to report on a great anti-Easter poem, which still has the power to surprise and provoke. I claim no great discoveries here, but the work in question is nothing like as well-known as it should be, at least in the US.

As everyone knows, many educated and elite figures in the Christian West experienced a crisis of faith in the nineteenth century. A crucial part of that story was the emergence of Biblical Higher Criticism, originally in Germany, and symbolized by the publication in 1835 of David Friedrich Strauss’s Das Leben Jesu (George Eliot translated his book into English). When this cultural revolution is discussed in the British context, it is more or less compulsory to quote from Matthew Arnold’s “Dover Beach,” with the famous declaration that

The Sea of Faith

Was once, too, at the full, and round earth’s shore

Lay like the folds of a bright girdle furled.

But now I only hear

Its melancholy, long, withdrawing roar.

The poem appeared in 1867, but it was written much earlier, before 1851, and likely in the year 1849.

That dating is important, because 1849 is also the setting for another very notable poem, written by Arnold’s good friend, Arthur Hugh Clough (1819-1861). Although Clough’s reputation has fluctuated over time, he now stands very high in critical esteem. Craig Raine writes that “He is, all the same, a great Modernist poet before Modernism, truly avant-garde, a radical genius of experimentalism. … His poetry shows a nimble ironist who cut genuine pathos with bold deadpan bathos – they co-exist.” Some of his sexual material is amazingly frank for its time, to the extent that even today, I would be a bit nervous about offering any extended quotes in the context of the Anxious Bench. He could also be really funny, and I will return to his satirical writing at the end of this post.

Clough lived through the religious excitement at Oxford in the 1830s, the great age of the Tractarians and the Oxford Movement, but he lost his faith, or at least in any orthodox form.In his Epi-Strauss-ium (1846?) he imagined seeing the sun’s light shining through stained glass windows in which he saw

Matthew and Mark and Luke and holy John

Evanished all and gone!

He lives in a world “After Strauss”, that is after David Friedrich Strauss, who had demolished faith in the canonical gospels, and specifically the tales of the Resurrection. Yet if the orthodox landmarks were gone, true Light could still shine and illuminate the world. Clough flirted with Unitarianism, and met Ralph Waldo Emerson on his visit to England. When the two separated, they bemoaned the spiritual struggles of young thinkers in England, who were wandering so far from faith but had not yet found a home. Emerson reported that

I put my hand upon his head as we walked, and I said, ‘Clough, I consecrate you Bishop of All England. It shall be your part to go up and down through the desert to find out these wanderers and to lead them into the promised land’.

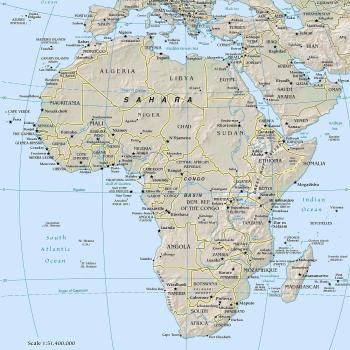

Clough traveled widely during his life, and he had many American connections: he even spent some childhood years in Charleston, SC. Even so, he was most attached to Italy, a land then in the midst of sweeping revolutions. This gave him material for his Amours de Voyage, a highly readable verse novel describing travels through Italy during the political crisis of 1848-49. The poem includes some strikingly immediate and journalistic (almost televisual) accounts of the riots and street battles in Rome during the nationalist revolution.

The poem gives a terrific sense of being in the center of great historical events and even having the status of an eye witness, but still being really uncertain what is actually happening:

So, I have seen a man killed! An experience that, among others!

Yes, I suppose I have; although I can hardly be certain,

And in a court of justice could never declare I had seen it.

But a man was killed, I am told, in a place where I saw

Something; a man was killed, I am told, and I saw something.

That awareness of the dangers of unreliable narration echoes Clough’s critical reading of the gospels.

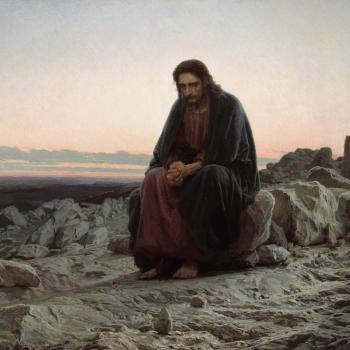

In 1849, he was in Naples at Easter, where he witnessed the luxurious ceremonials, and heard all the bells and choirs proclaiming the Resurrection. How could anyone resist a new commitment to faith, however temporary?

Well, Clough did indeed resist, and he described his reactions in the poem “Easter Day”, with its repeated declarations contesting faith. He is almost describing a conversion experience, the diametric opposite of how evangelicals described being born again. Note the familiar evangelical language of heat, warmth and fire, recalling John Wesley’s heart being “strangely warmed.”

Through the great sinful streets of Naples as I past,

With fiercer heat than flamed above my head

My heart was hot within me; till at last

My brain was lightened, when my tongue had said—

Christ is not risen!

Christ is not risen, no,

He lies and moulders low;

Christ is not risen.

With slight variations, that last line becomes the refrain of each stanza.

I will only offer selections here, as you can find the whole work easily enough. Repeatedly, Clough cites the weaknesses of “the Gospel,” which evidently shows his familiarity with Higher Criticism:

What if the women, ere the dawn was grey,

Saw one or more great angels, as they say,

(Angels, or Him himself)? Yet neither there, nor then,

Nor afterward, nor elsewhere, nor at all,

Hath He appeared to Peter or the Ten;

Nor, save in thunderous terror, to blind Saul;

Save in an after-Gospel and late Creed

He is not risen indeed,

Christ is not risen.

Or what if e’en, as runs the tale, the Ten

Saw, heard, and touched, again and yet again?

What if at Emmaüs’ inn and by Capernaum’s Lake

Came One the bread that brake—

Came One that spake as never mortal spake,

And with them ate and drank and stood and walked about?

Ah! ‘some’ did well to ‘doubt’!

Ah! the true Christ, while these things came to pass,

Nor heard, nor spake, nor walked, nor dreamt, alas!

He was not risen, no—

He lay and moulder low,

Christ was not risen.

Like the Higher Critics of the day, Clough was very concerned with dating the various New Testament texts precisely, and tracing the development of doctrines over time: hence the reference to “after-Gospel and late Creed.”

The whole long poem (a thousand words) is an essay as much as a lyric. It is an extended meditation on the denial of Resurrection, and with it, the need to construct a valid world without religious faith, or at least not in any sense that the term was used at the time:

Eat, drink, and play, and think that this is bliss:

There is no Heaven but this;

There is no Hell;—

Save Earth, which serves the purpose doubly well,

Seeing it visits still

With equallest apportionment of ill

Both good and bad alike, and brings to one same dust

The unjust and the just

With Christ, who is not risen.

Eat, drink, and die, for we are souls bereaved

Of all the creatures under heaven’s wide cope

We are most hopeless, who had once most hope,

And most beliefless, that had most believed.

Ashes to ashes, dust to dust;

As of the unjust, also of the just—

Yea, of that just One too!

It is the one sad Gospel that is true—

Christ is not risen!

…

Here, on our Easter Day

We rise, we come, and lo! we find Him not,

Gardener nor other, on the sacred spot:

Where they have laid Him there is none to say;

No sound, nor in, nor out—no word

Of where to seek the dead or meet the living Lord.

There is no glistering of an angel’s wings,

There is no voice of heavenly clear behest:

Let us go hence, and think upon these things

In silence, which is best.

Is He not risen? No—

But lies and moulders low?

Christ is not risen?

Clough himself lived a difficult and tragic life, dying at the age of 42. After his death, another poem of his was found, which at least seems to reverse that stark 1849 original, although it is even less celebrated. “Easter Day II” is in no sense a simple affirmation of faith, as it rejects any physical or literal Resurrection. But even so, he leaves space for the belief that, in a spiritual or liturgical sense, Jesus still lives:

Though He be dead, He is not dead,

Nor gone, though fled,

Not lost, though vanished;

Though He return not, though

He lies and moulders low;

In the true creed

He is yet risen indeed;

Christ is yet risen

….

In the great gospel and true creed,

He is yet risen indeed;

Christ is yet risen.

If we can’t claim any kind of deathbed conversion, Clough did find his way to seeing value in faith. In modern language, we might think in terms of cultural Christianity.

After discussing those weighty texts, I can’t resist quoting the whole text of one Clough poem that illustrates his power as a satirist, in this case attacking established religion and hypocritical bourgeois morality. He helpfully offered the mid-Victorian world an updated version of the Ten Commandments, the “Latest Decalogue”:

Thou shalt have one God only; who

Would tax himself to worship two?

God’s image nowhere shalt thou see,

Save haply in the currency:

Swear not at all; since for thy curse

Thine enemy is not the worse:

At church on Sunday to attend

Will help to keep the world thy friend:

Honor thy parents; that is, all

From whom promotion may befall:

Thou shalt not kill; but needst not strive

Officiously to keep alive:

Adultery it is not fit

Or safe, for women, to commit:

Thou shalt not steal; an empty feat,

When ’tis so lucrative to cheat:

False witness not to bear be strict;

And cautious, ere you contradict.

Thou shalt not covet; but tradition

Sanctions the keenest competition.

Yes, he is still very much worth reading.