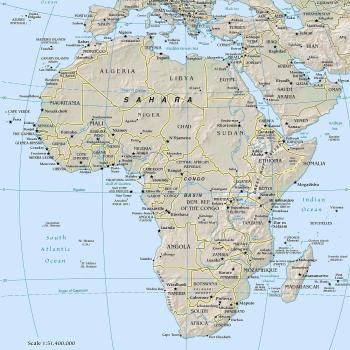

Last time I wrote about the amazing growth of Catholic populations in Africa, to the point that they would very soon outnumber European believers. But beyond the raw fact of numbers, the African church has many features that distinguish it sharply from our familiar Western concepts. Each, to varying degrees, affects how those growing numbers will reshape the larger church as the years go by. I won’t go into any great detail here, as I have regularly discussed these topics in other writings through the years. But there are some major themes.

North and South

On average, believers are much poorer than Europeans, Moreover, many face the grave challenge of violence and persecution from other groups, chiefly Muslims. Particularly in a country such as Nigeria, the prospect of martyrdom is all too real. Sadly, this is all too relevant to the present Easter season, precisely because that is when jihadis are likely to carry out massacres and assassinations. Just last month, a bishop from Nigeria’s Middle Belt told the British Parliament that that for his people, their experience in recent times “can be summed up as that of a Church under Islamist extermination.” As African Catholics become more prominent in the global church, that horrific background cannot fail to affect issues of interfaith relations.

African Catholicism is also much different in terms of its levels of practice, and its strongly conservative nature, to a point that is hard to exaggerate. According to official figures, some of the world’s largest Catholic populations are still found on the European continent, in such nations as France, Italy, Spain, Portugal, and Germany, which between them notionally claim around 150 million believers. But levels of belief and practice are not necessarily high in societies in which the process of secularization is well advanced, and in many cases, that reported church membership is fairly notional. Because of the more recent conversion of those lands, active practice is far higher in African nations such as Nigeria, with its 35 million Catholics.

I offer one telling figure cited by John Allen, who measures mass attendance in the five west European nations I just mentioned. He observes that “collectively they have about 30.4 million Catholics who show up every Sunday.” Nigeria, in contrast, reports far fewer Catholics overall, but they are much more observant. Already today, “Nigeria alone has roughly the same number of regularly practicing Catholics as all of western Europe.”

Where The Numbers Are

And Nigeria does not even have the continent’s largest Catholic population: the Democratic Republic of Congo’s is far larger. Even in terms of notional adherence, the DRC’s 55 million believers give it a larger Catholic population than any European nation, including Italy. The DRC is presently the world’s fifth biggest Catholic nation, standing behind Brazil, Mexico, the Philippines and the USA.

That is today. Come back in a decade or so and expect to see the places of the European nations giving place to rising African nations in any list of leading Catholic powers. Besides the DRC and Nigeria, expect to see such high fertility nations as Uganda, Tanzania, Angola, Cameroon, and Kenya.

Reshaping a World Church

African Catholics are much more conservative on the moral issues that so agonize Northern world believers, which focus so sharply on matters of sexuality and gender. That global division was very apparent at the Synod on the Family back in 2015, and it came close to an outright explosion in 2023 when the Vatican issued what was initially seen as a form of blessing for same-sex couples. I recently discussed this whole fiasco.

Put another way, the Vatican in coming years has to tread very carefully indeed on such matters. Does it speak to the very numerous and increasing Africans, who favor cultural tradition, or to the daring and innovative Europeans, whose numbers are shrinking so visibly and painfully? And that is over and above the question of relations with Muslim leaders, a topic that for African leaders has an existential quality.

Cardinals and Popes

As I noted recently, I don’t think the forthcoming Papal election is likely to produce an African Pope, at least on this occasion, but such an outcome cannot be long delayed. For one thing, the African element in the church’s leadership has been growing steadily.

The first Black African cardinal was Tanzanian Laurean Rugambwa, appointed in 1960 in what was at the time regarded as a bold stroke. Presently, there are 29, of whom 18 are below eighty years of age, and therefore eligible to vote in Papal elections. Africans thus constitute thirteen percent of the active electoral college. Although that is a phenomenal increase over the past half century, it still falls short of proper representation: Africans, as I remarked, now constitute twenty percent of overall Catholic numbers. By rights, there should already be another ten African cardinals, and perhaps there soon will be.

Some of those leaders have already appeared on lists of potential Popes. As I have noted Ghana’s Peter Turkson has appeared on many lists, as has Fridolin Ambongo Besungu, of the DRC. At 77, Turkson may well be too old, but Besungu is a relatively youthful 65, and we can expect him to be a player in Vatican politics for a good few years to come. So will Tanzania’s Protase Rugambwa, who was named for that historic pioneer, Laurean Rugambwa, whom I just mentioned: however suspiciously nepotistic the name might sound, it honestly is nothing of the sort! He is presently 64.

Guinea’s Robert Sarah has for some years appeared as a distant outsider. Even by African standards, Sarah would be a very conservative choice indeed, and he ostentatiously loathes Western liberal positions on sexual matters. He frames global conflicts in apocalyptic terms, declaring that “What Nazi-Fascism and communism were in the 20th century, Western homosexual and abortion ideologies and Islamic fanaticism, are today.” Happily for Western liberals, he will soon hit the disqualifying age of 80, which would remove him as a Papal elector – but not, interestingly, as a Papal candidate, where age limits do not apply.

Not all prelates are so fiery, and many support progressive views on issues like climate change. What unites African leaders, though, is a resolute defense of church tradition, commonly against the perceived danger of assaults from secularized Catholics in Europe or the U.S. All the African prelates, naturally, condemn abortion, and most reject permitting the use of condoms. Few are even on record for their views on same sex marriage, as the issue is so far from the political agenda of most African nations, outside South Africa.

One way or another, a church with a growing African presence – one third of all believers by 2050! – is going to differ substantially from anything that we might expect presently.