Yesterday morning, I received a startling email from my sons’ Little League head coach: one of the assistant coaches, a father of their teammate, had unexpectedly died. The news had my husband and me reeling. We had just seen this dad at a team gathering after our last game. We had joked with him. He and I talked about whether we prefer people to pronounce our name in Spanish or English (he said either; I said Spanish). And now he’s gone. His wife and two young sons are left behind. Broken.

***

I’ve been meditating a lot on suffering this Lent. Daily, in fact, via Hallow, my Catholic prayer app. In Pray40, with St. Josemaría Escriva’s The Way as an anchor, we’ve been examining what it means to follow Christ’s Way and have been challenged to approach these 40 days of wandering with Christ in the desert differently this year. To view Lent as a training ground.

A priest explains in the first Sunday Sermon of the series that the heart of asceticism is ascesis, which means training: “And so we find ourselves in Lent in a certain kind of dojo, right? The training room, ‘the place of the way,’ right? Dojo in Japanese and English means ‘the place of the way.’ Because why? Because at the end of this Lent, we want to be able to do something that we cannot currently do. At the end of this Lent, I want to be someone that I am currently not… the goal of Lent is to look like Jesus. And I don’t currently look like Jesus. I don’t currently think like Jesus. I don’t currently love like Jesus… In order to be able to do something I cannot currently do, I have to begin to do something that I’ve not yet done” (Fr. Mike Schmitz, Pray40 Day 5: Sunday Sermon).

How can we do something we’ve not yet done?

Pray40 has been taking us through Paul Glynn, S.M.’s new biography of Takashi Nagai, A Song for Nagasaki, published in February 2025 by my friends at Ignatius Press. A Japanese husband, father, and physician who survived the 1945 atomic bombing of Nagasaki, Nagai is under consideration for canonization by the Catholic Church for his incredible witness to God despite incredible loss.

Yesterday morning, as I commuted 90 minutes to teach, I reached the end of the book, Takashi Nagai’s death in 1951, whose funeral drew twenty thousand mourners into and around the rebuilt Urakami Cathedral, onto which the bomb had dropped. The church’s lone bell rang out at noon, joined by bells in other church steeples and Buddhist temples, as well as by factory whistles, and horns and sirens from every boat in Nagasaki Harbor. The city fell into silence to honor the passing of a beloved citizen. This was man who had lost so much, yet had guided the city to a place of peace by arguing that the bombing Nagasaki was a gift from God.

I’m sorry, what? That’s what the people of Nagasaki initially said. And that’s what I said.

I encourage you to read about this extraordinary man yourself, but here’s an overview: born in 1908 in rural Japan, Takashi Nagai was raised in a home guided by Shinto and Confucian principles, thought by high school he had become an atheist. Viewing science as the only reality, he chose to study medicine at Nagasaki University. After witnessing his mother’s death, he became convinced that the soul existed and searched for answers, moved by the writings of Christian philosopher, Blaise Pascal. After completing his studies and becoming a radiologist, he decided that living with a Christian family was the best way to learn how to pray. Walking to the Catholic neighborhood of Nagasaki, he knocked on a random door and the family agreed to take him in as a boarder. In a providential twist, this home happened to be the headquarters of the underground Catholic Church during the 300 years that Christianity had been banned in Japan.

Takashi witnessed the daily prayer life of the family, surprising even himself when he agreed to attend Christmas Eve Mass in 1931 at the Urakami Cathedral, which seated over 5,000 people. That night would profoundly change him, for he left Mass certain there was a living Someone in the cathedral.

Takashi would spend time in military service in China, taking with him a catechism and summary of the teachings of the Catholic Church, a gift from Midori, the 23-year-old daughter of the family with whom he had been living. Nevertheless, the pain and suffering he witnessed caused him to despair, and he returned to Nagasaki a broken man. A priest at the Urakami Cathedral introduced him to a Catholic mentor, a janitor at the hospital where Takashi worked, and eventually he received baptism, taking the name Paul Miki, the leader of the 26 martyrs of Nagasaki crucified for their beliefs. He and Midori married and started a family, and despite economic hardship and poor health, he found time to serve the poor through a local chapter of the Society of St. Vincent de Paul.

In the years that followed, Takashi lived out St. Josemaría Escriva’s words: “We lost sight of the simple fact that might easily overlook. We will not be able to share in our Lord’s resurrection unless we unite ourselves with him in his passion and death” (Christ is Passing By, 95). Called away from his family to serve for three years as chief surgeon in the army during a renewed war against China, he returned to Japan in 1940. The following year, while walking home from 6am Mass with Midori on December 8, 1941, loudspeakers announced the attack on Pearl Harbor and he had the strange premonition that the buildings around him would be destroyed. A tuberculosis epidemic gripped Japan during WWII, requiring him to pass long hours at the x-ray machine. Noticing Takashi falling asleep at work, his colleagues persuaded him to be x-rayed and discovered that he had developed incurable leukemia with a life expectancy of two to three years.

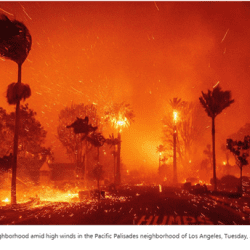

Yet God preserved him. On August 6, 1945, news came of the bombing of Hiroshima, prompting Takashi and Midori to send their children into the country with her mother. We all know what comes next. After cloud cover and issues with the auxiliary gasoline pipe made it impossible to drop the bomb on the intended target city of Kokura, the pilot turned towards the second target: Nagasaki. Two miles northwest of the planned drop, and with time running out, the pilot took advantage of a break in the clouds and dropped the bomb on the Urakami Cathedral, where Takashi’s friends and fellow parishioners had gathered to participate in the sacrament of Confession with several priests.

The book graphically details the devastating effects of the bomb, but I will not relate them here, except to say that Takashi spent several days in the hospital helping the injured before stumbling down to the ashes that was once his neighborhood. There he found the remains of his beloved Midori, rosary beads melted into her right hand. That’s when he broke down and cried.

How does one go from being this broken, to suffering such loss, to being at peace?

Surrender.

In November, after miraculously recovering from A-bomb sickness and moving back into his demolished neighborhood with his children, Takashi received an invitation from the archbishop of Nagasaki to speak at an outdoor Mass for the dead. Crowds of bandaged, disfigured, and demoralized Catholics gathered, eager to hear words that would help them make sense of their loss and suffering. What could Takashi possibly say?

His speech deserves a lengthy quotation:

“On the morning of August 9th, the world stood at a crossroads. A decision had to be made, peace or further cruel bloodshed and carnage. Just at 11:02 A.M., an atom bomb exploded over our suburb. In an instant, 8,000 Christians were called to God and at midnight that night, our cathedral suddenly burst into flames and was consumed at exactly the same time in the Imperial Palace, His Majesty the Emperor had made known his decision to end the war. And on August 15, the Imperial Rescript, which put an end to the fighting, was formally promulgated and the whole world saw the light of peace…

I have heard that the atom bomb was destined for another city. Heavy clouds rendered that target impossible, and the American crew headed for the secondary target, Nagasaki. It was not the American crew, I believe, who chose our suburb. God’s Providence chose Urakami and carried the bomb right above our homes… (A Song for Nagasaki as quoted in Pray 40, Day 19: Sunday Sermon and Day 28: Speech on the Hallow app).

Several in the crowd rose and shouted in protest, but having walked through the dark valley himself, he continued, neither surprised nor upset:

“Is there not a profound connection, relationship between the annihilation of Nagasaki and the end of the war? Was not Nagasaki the chosen victim, the land without blemish, slain and whole burnt offering as an altar of sacrifice, atoning for the since of all the nations during World War II?

We are all inheritors of Adam’s sin. We are all inheritors of Cain’s sin. He killed his brother. And yes, we have forgotten love, hating one another, killing one another. Yes, even joyfully killing one another. At last the evil and horrific conflict came to an end, but mere repentance was not enough for peace. We had to suffer a stupendous sacrifice. Cities had been leveled, but even that wasn’t enough. Only this sacrifice of Nagasaki sufficed…

The Christian flock of Nagasaki was true to the Faith through three centuries of persecution. During the recent war, it prayed ceaselessly for a lasting peace. Here was the one pure lamb that had to be sacrificed, on His altar, so that many millions of lives might be saved…

In the depths of our grief, like in this valley, we will be able to gaze up and see something beautiful, pure, and sublime. Happy are those who weep. They shall be comforted… We must walk the way of reparation, ridiculed, whipped, punished for our crimes, sweaty and bloody, But we can turn our minds’ eye to Jesus carrying his Cross to the hill of Calvary. The Lord has given; the Lord taketh away. Blessed be the name of the Lord…

Let us be thankful that Nagasaki was chosen for the whole burnt sacrifice! Let us be thankful that through this sacrifice, peace was granted to the world and religious freedom to Japan” (A Song for Nagasaki as quoted in Pray 40, Day 19: Sunday Sermon and Day 28: Speech on the Hallow app).

In the Sunday Sermon that contextualized this speech, the priest acknowledged the difficulty: “So what I’m going to share today, I have a sense that many, if not most of us will find it hard to hear. And I think that many of us, if not most of us, will find it even more difficult to understand, and probably all of us will find it very, very difficult to accept… that we might hate this (Fr. Mike Schmitz, Pray40 Day 19: Sunday Sermon).

Returning to the metaphor of Lent as God’s dojo, a place of “The Way,” Fr. Schmitz repeated the challenge to use these 40 days to train to look like Jesus, to love like Jesus. He said that the kind of Jesus we’re training to be is not the glorious Christ of Mount Tabor, but the Christ of Calvary, the Christ who can ask his Father to forgive those responsible for his suffering, for his death. He argues that the place of the way, the place of training to look like Jesus is not the peak, it is in the valley. In the valley is where Takashi Nagai himself encountered Christ, leading him to believe that the atom bomb falling on Nagasaki was no accident or punishment, but rather an opportunity to participate in God’s redemption.

I was so startled the day I heard this – while on my 90-minute commute to teach – that I shared Takashi Nagai’s interpretation of the bombing of Nagasaki with my students and we all sat in stunned silence with his words. I remain stunned.

***

“Unless you have suffered and wept, you really don’t understand what compassion is, nor can you give comfort to someone who is suffering. If you haven’t cried, you can’t dry another’s eyes. Unless you’ve walked in darkness, you can’t help wanderers find the way. Unless you’ve looked into the eyes of menacing death and felt its hot breath, you can’t help another rise from the dead and taste anew the joy of being alive.” –Takashi Nagai, A Song for Nagasaki as quoted in Pray 40 Day 35: Visitors