We are running out of prophecies.

Let me explain. I have been writing about what seems to be the near-future likelihood of a Papal conclave, and the choice of a new Pope. For centuries, the assembled Fathers have made their choice through a mix of power politics and exalted visions, but remarkably often, at least into the present century, someone present has imported a mystical theme, in the form of a seductive prophecy, and that is about to expire. I will explain that theme, and suggest how, even if you do not believe a word of it, it really could lend an apocalyptic tone to any forthcoming deliberations. On a related topic, I will be looking at the equally pervasive association of the Papacy with apocalyptic dreams and visions of Antichrist.

St. Malachy’s List

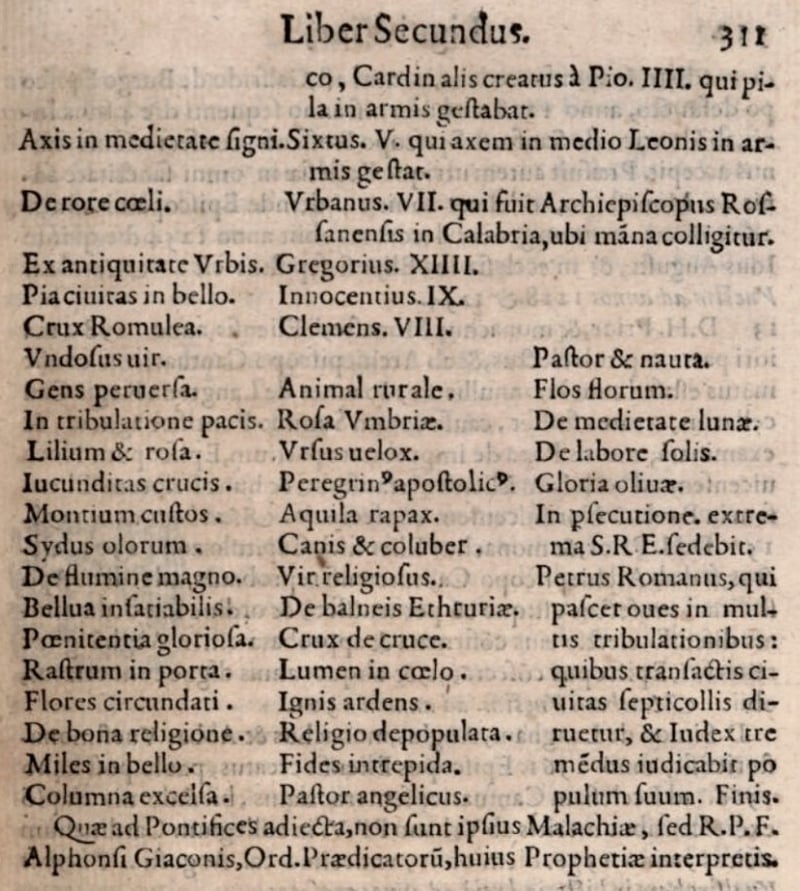

The prophecy I have in mind is attributed to the twelfth century Irish wonderworking saint Malachy, and it takes the form of a list of future Popes, with each one attributed a short motto that reveals his character. By common consent, the actual document was drawn up around 1590, and not surprisingly, the “prophecy” is very accurate up to that date, but then goes astray. Even so, the mottos inspired enormous speculation, and especially around the time of a new Papal election. Bizarrely, Malachy was often cited by participants in the twin conclaves of 1978, and surfaced again in 2005.

You can read an amazing volume of recent writings by quite sane people striving to fit current Popes into that scheme. The one who corresponds to John XXIII was Pastor et nauta, shepherd and sailor: and he had been Patriarch of Venice, a seagoing city. And then there is the truly spooky one, De medietate lunae, of the half-moon, which suggests something short-lived, something that falls short of maturity. In the order of Popes, it corresponds to John Paul I, who reigned for an incredibly brief 33 days in 1978 (Cue Twilight Zone theme).

After John Paul I, you have John Paul II, De labore solis, the labors of the sun. He was the Polish Pope, the first in centuries from the cold north. Well, it sort of works, if you are trying hard. Then there is Benedict XVI, Gloria olivae, and I have no idea how true believers would explain that one. Glory of Olives?

But then, if it was not weird enough already, it gets very weird indeed. The text is confused, but it seems to point to a Pope called Peter the Roman, Peter II, who receives not just a motto but a full narrative referring to “the final persecution of the Holy Roman Church”:

Peter the Roman, who will pasture his sheep in many tribulations, and when these things are finished, the city of seven hills will be destroyed, and the dreadful judge will judge his people. The End.

The Pope who corresponds in the sequence is Francis, who logically, should be the last of all. Assuming he is not, and the papacy continues, it will be fascinating to see how Malachy-believers explain that. It would add to the sizable Religious Studies literature on the theme of “When Prophecy Fails.”

Did you know the papacy has an expiration date?

The Pope of the Apocalypse

The connection between the Papacy and the End Times is familiar enough in Protestant literature, where Popes were seen as Satanic, and their Fall was a major positive feature of the apocalyptic overthrow of evil. But there is also a pervasive Catholic interest in the topic.

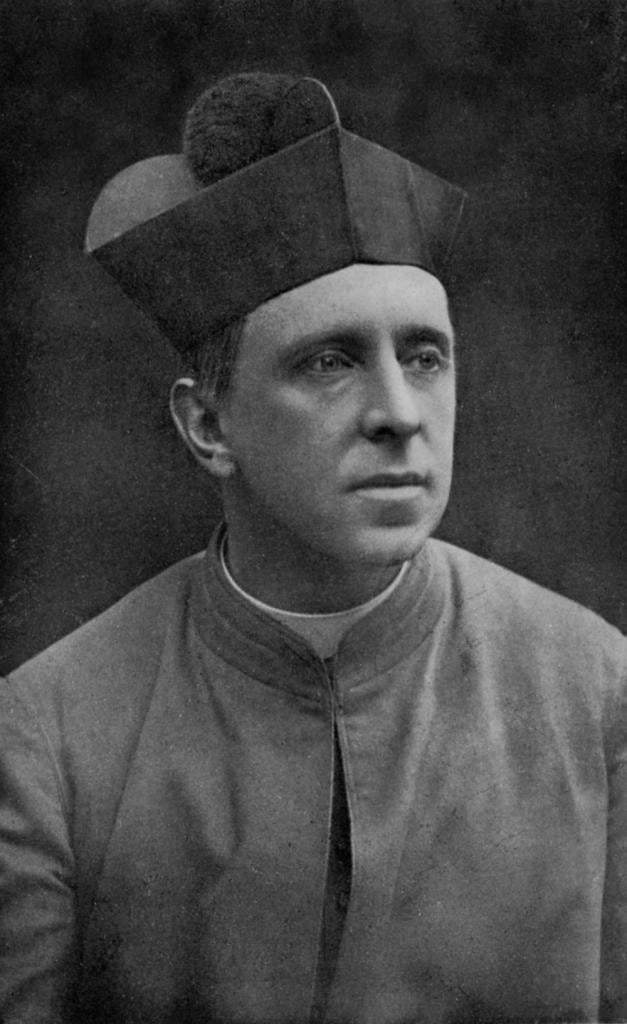

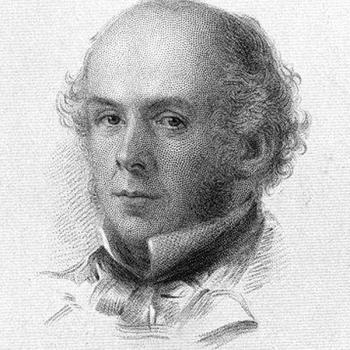

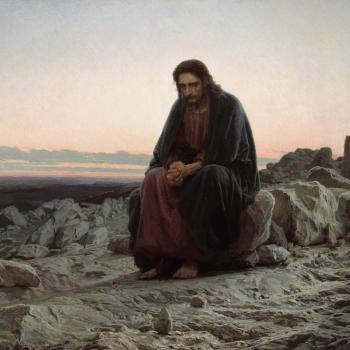

The classic example is in the work of Robert Hugh Benson, who used the Papacy in his ultimate Antichrist novel, Lord of the World (1907). Benson came from a family too strange and too talented to have been invented. His father was an Archbishop of Canterbury, his brother was the superb novelist E. F. Benson, and the whole clan is the subject of a fine and aptly titled collective biography by Simon Goldhill, A Very Queer Family Indeed: Sex, Religion, And The Bensons In Victorian Britain (University of Chicago Press, 2016). R. H. Benson converted to the Catholic Church, and became a priest. He counted among his closest friends Frederick Rolfe, about whose Papal fantasies I wrote in my last blogpost here.

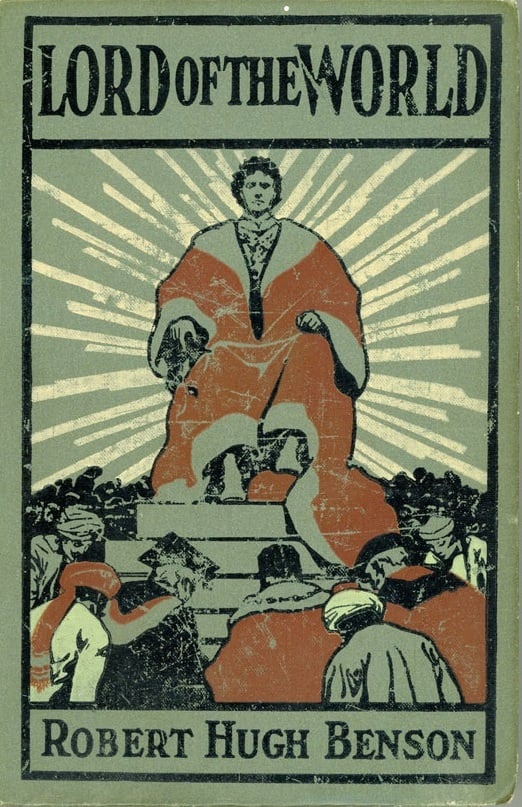

Though best remembered for his persecution novel Come Rack Come Rope, Benson was well known in his own day for what might be described as an anti-scientific romance which turned the work of H. G. Wells on its head. This was the best-selling Lord of the World, an extraordinarily dark novel which describes the near-extermination of Christianity less through violence and persecution than through the mass defection of the world’s people to a new order based on science, secularism and reason. It also draws heavily, and unmistakably, on that closing section of the prophecies of St. Malachy.

Lord of the World

Published as I say in 1907, Lord of the World begins with an imaginary history of the coming twentieth century, which at first reads as if it has been scripted by Wells himself. Once the Labour Party wins power in England in 1917, a century of Communism and secularism began in earnest. The Protestant churches cave in before the threat, swiftly abandoning the Nicene Creed and the Divinity of Christ, together with faith in Biblical inspiration. The “sheep and goats” are severed into two different camps. In the minority, “the religious people were practically all Catholics and Individualists”, while the great mass of the population are materialist, collectivist, and Communist. Benson was here following the famous prophecy of England’s Cardinal Manning that within a few decades, the only political division in Europe would be the battle between Catholicism and Communism.

Dogmatic secularism reigns in education, private property is abolished. Over all presides the Masonic elite, and their simple creed: “God is Man”. When I first read this book at Penn State many years ago, I was amused to see that the university library there catalogued this ultimately apocalyptic work in its “utopian” collection, presumably on the basis that its prophecies sound heartening.

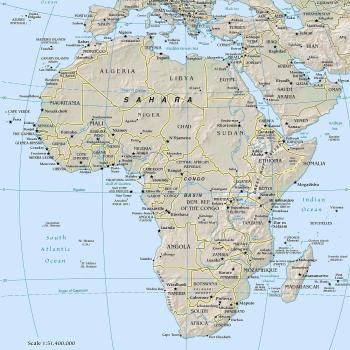

Gradually, the new world order finds a more or less human face in Julian Felsenburgh, the brilliant statesman who establishes world peace and Universal Brotherhood, and becomes the Lord of the World. With such obvious testimony to the glory of secularism and socialism, even the bulk of the remaining Catholic clergy and laity join the mass defection to his cause, which is that of the Antichrist. At this stage, the final persecution of Catholics and Individualists can begin, culminating in the sack and massacre of Rome, and the reduction of the world’s Christians to a few million clandestine believers. Alleged Catholic conspiracies justify the final pogroms that clear England of its churches. The official press crows that “London is cleansed at last of dingy and fantastic nonsense.”

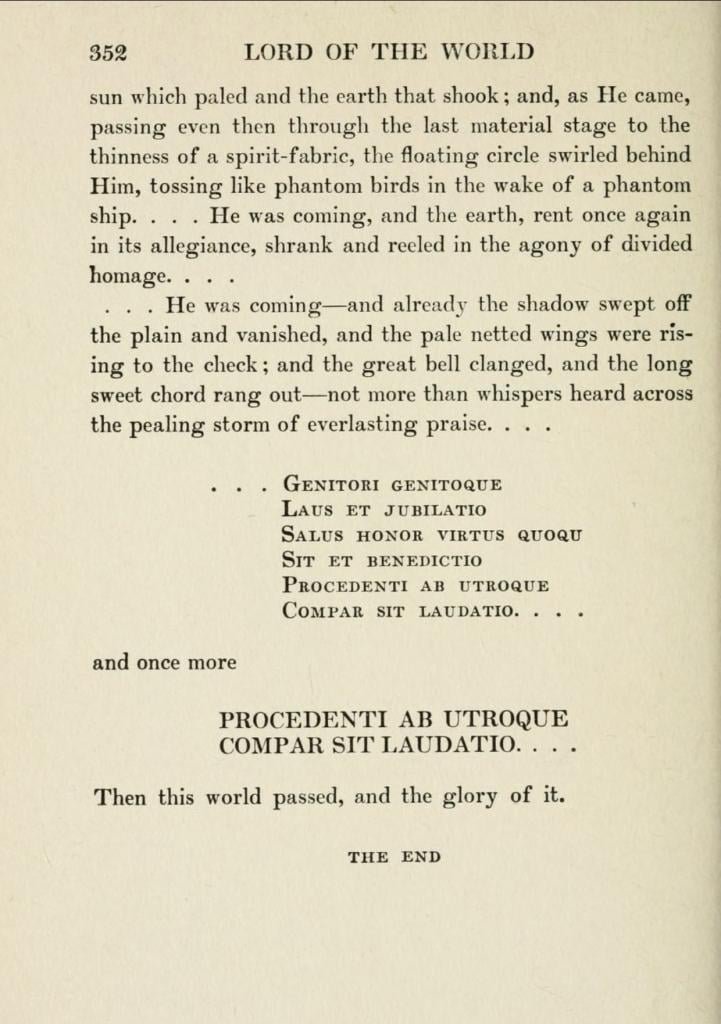

Finally, in scenes that were remarkably daring for a priest of this age, the institutional church is reduced to something very like its origins, of the Pope and twelve Cardinals, and one of them is a traitor. The Pope, who is in some mysterious sense the physical double or mirror image of Felsenburgh, returns to Nazareth to await the end. As the forces of persecution close in, Christ vindicates his promise that the church should endure to the end of the world, and that very end commences among the duel of Principalities and Powers: “Then this world passed and the glory of it”. And finally, words with much greater significance than customary in a novel: THE END. Again, this conjures shades of Malachy, who ends simply Finis.

The Latin words here are drawn from the Tantum ergo sacramentum, which is associated with the adoration of the sacrament. For Benson, the Eucharist was a central symbol of apocalypse and Judgment.

The Dawn of All

Interestingly, Benson was most severely criticized not by the liberal secular contemporaries whom he was berating as the unwitting dupes of the Devil, but by his strictest Catholic allies, who were appalled at the thoroughly depressing portrait of the future of the Church. Partly in penance, in 1911 he published a diametrically opposite novel entitled The Dawn of All, which employed the familiar Victorian device of a modern man transported to a future age in which some Great Change has been accomplished: Think of Edward Bellamy’s Looking Backward, from 1888. Bellamy’s work established the fashion for having observers glance back over the whole glorious twentieth century, the model imitated in the “historical” opening of The Lord of All.

Most such utopian visions were socialist or scientific in tone, but in Benson’s case, the “revolution,” the “dawn of all”, has been the recatholicization of England and the world, and the establishment of a Chestertonian world of family, religion and small property. The guilds are the cornerstone of economic life, and families are so valued that each woman is happy to bear eight or ten children. The new England is either the kingdom of God made manifest, or at least a powerful foretaste of that kingdom. We glimpse only at a far distance the Catholic glories of the newly Christian lands of China and Japan. The book is perhaps less an apologia than a simple apology, namely for Lord of the World, and it is far less convincing than its dystopian predecessor.

The Dawn of All has its merits, but it does not come close to The Lord of the World. That latter book also foreshadows so many of the themes that have made bestsellers of later Antichrist novels like the Left Behind series.

I will be watching the next conclave with great interest to trace subtle memories of Malachy, and even Soloviev. Dare I suggest that such nightmares are likely to find whole new audiences in a Europe increasingly alarmed by war scares?

I would appreciate assistance on one point, namely where Benson is finding his material. He must be drawing on Malachy, but over and above that he is very probably using Vladimir Soloviev’s classic Story of the Antichrist (1901). Soloviev ends with a struggle between the Antichrist and the leaders of the great churches, and the Roman Catholics are led by Peter II, a direct bow to Malachy. Soloviev wrote in Russian, and the earliest English translation I can find dates to 1915, which is way too late for my present purposes. Even so, the resemblances between Soloviev and Benson are very strong indeed. Am I missing an earlier translation? Or were these ideas just “in the air” at this time? I know that Constance Garnett was publishing her famous Tolstoy translations at or before the turn of the century. Did Benson and Garnett have any friends in common who might have told him what Soloviev was doing?