Over the past decade, an interest in the transpacific has transformed scholarship on American Christianity. As Helen Jin Kim argued in Race for Revival: How Cold War South Korea Shaped the American Evangelical Empire, “it simply is not possible to understand evangelicalism without looking at transnational linkages and movement across the Pacific, especially when we move into the twentieth century.”

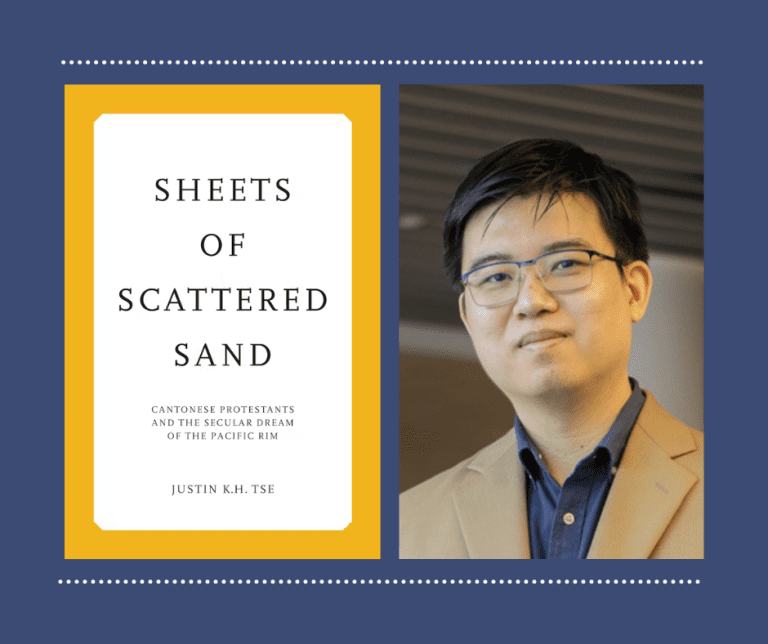

Justin Tse, a religion scholar and geographer at Singapore Management University, offers one of the most exciting contributions to the growing body of research on transpacific Christianity. In his new book, Sheets of Scattered Sand: Cantonese Protestants and the Secular Dream of the Pacific, which was published by Notre Dame Press earlier this month, Tse studies Christian communities in the Pacific Rim, a region that he views “more as a dream than as a regional geography, its work as a fantasy engine that powers civil society imaginations.” He focuses his attention on Hong Kong, Vancouver, and the Bay Area and explores how Cantonese Protestants in these locales engaged in politics and secular civil society, especially as they mobilized around controversial issues such as gay marriage and democratic reforms. In his telling, Cantonese Protestants are a “sheet of scattered sand”–characterized by diversity, disunity, dysfunction, and disorganization. However, they are united by the experience of being drawn into participating in the secular world of politics, and sometimes with great reservation, since many Cantonese Protestants believed that the church and the secular world should be separate.

I had the good fortune of discussing Sheets of Scattered Sand with Tse at the American Academy of Religion Annual Meeting this month. Our conversation has been edited for clarity and brevity.

Melissa Borja: What is the central argument of your book?

Justin Tse: The central argument of [this book] is that Cantonese-speaking Protestants who were trying to engage the Pacific Rim societies of Vancouver, San Francisco, and Hong Kong from around 1989 to 2012 described themselves as “sheets of scattered sand.” They described themselves as ideologically fragmented and politically disunited. There are actually two parts to this. One is what they described as political and ideological fragmentation. They were fragmented around a central anxiety, and that anxiety had to do with the world outside of their churches that they described as secular.

What I then argue about that secular is that it’s a Pacific Rim secular. The Pacific Rim is a set of narratives and ideologies that basically propose a transpacific frame, in which Asia and the Americas should somehow coalesce together around the Pacific Ocean as a rim and create a kind of Asian multicultural society that lends itself to geopolitical stability, economic co-prosperity, and ecological sustainability. The secular outside of Cantonese Protestant churches was continuing to transform. Between 1989 to 2012, Cantonese Protestants were very nervous about that and were often fragmented around what the Pacific Rim secular is and how they should respond to it.

MB: So how does it help us think differently about Asian and Asian American religious life?

JT: Oftentimes when we try to describe Asian and Asian American religious life, we think culturally. We think about identity. And so there is a real temptation to attribute this fractiousness to either Cantonese Protestants being Cantonese–you know, mostly from Hong Kong or South China–or that they had some kind of essentialized Chinese culture, or that they were Christian or Protestant Christian, and so for a set of religious reasons, they were fragmented. And what I propose is no. When we think of a sheet of scattered sand, the scattered sand is scattered on a sheet or in a container. And that means that the sheet and the container has to be external to their communities.

So how it makes us think differently about Asian and Asian American religious life is to ask us to consider what, outside of our communities, is the thing that our communities are responding to, or what structures impinge on our communities. In my book, it’s the Pacific Rim secular.

MB: We just did a roundtable about new scholarship about religion and the transpacific. How do you define transpacific, and how does understanding experiences of Cantonese Protestants help Asian American studies scholars think anew about the transpacific?

JT: I take my cue from the late Gary Okihiro. Gary Okihiro writes in Margins and Mainstreams, one of his first books, that Asians did not go to America–America went to Asia. Now, these are two statements about the transpacific. How we normally think about the transpacific is that Asians went to America. We follow the journey of Asians as they immigrate to America. But what actually makes that journey possible is the transpacific migration of an American social formation. We might call that American empire across the Pacific. My definition of the transpacific actually revolves around those structures.

I actually call the transpacific in my book the Pacific Rim. The Pacific Rim is this kind of outdated term. I was thinking about where I first heard this term. It was actually in a novel by a Vancouver novelist, Timothy Taylor, titled Stanley Park. And in the middle of the book, he uses this term Pacific Rim, and it’s basically white people eating sushi. And so the Pacific Rim is this transpacific imaginary of this Asian, multicultural society that can be built mostly to serve the interests of white people. But Asians get implicated in this, and that leads to them migrating. The Cantonese Protestants in my book migrate from Hong Kong to San Francisco and Vancouver and sometimes return to Hong Kong. So the transpacific is not just them migrating. It’s not just their transpacific journeys of migration, but it’s the structure that makes that migration possible.

MB: I really found fascinating in your book your description of the different forms of political engagement. I know that your book focused on this period between 1989 and 2012, but I wonder if you could share how the communities at the center of your study responded to political events since then–for example, anti-Asian racism and violence during the Covid-19 pandemic and surging tensions between the US and China.

JT: That’s a really good question. I didn’t have any interviews after 2012, but there was a reason why I didn’t go out and get more, which is that in 2012, there’s a new sheriff in town on the Pacific Rim, and there’s the rise of what you might call Chinese cultural nationalism. And how that starts is China gets a new leader. It’s this guy named Xi Jinping. Basically, over the last 12 years, he has spread his ideology of the China dream: Chinese people are all linked together by one blood, we’re all brothers, all Chinese people are the same. That leads to a new set of politics.

First, it leads to a new set of Asian American politics. This is the time when Chinese people are so proud of themselves and therefore participate in activism against affirmative action because they feel like they are being discriminated against or reverse discriminated against by what they see as quotas in affirmative action policy. This is the time when they come out for this guy named Peter Liang, who was a Chinese American police officer in New York, who killed a man by firing a Black man, by firing his gun into what he thought was an empty stairwell. Chinese Americans felt that he was scapegoated. Why didn’t the NYPD go after white police officers? Chinese people are getting a new awareness of themselves as Chinese people and needing to be united.

At the same time, there are protests against that unity. So this is the time also of the Hong Kong protests, when Hong Kong people are like, we don’t call us Chinese, we’re not from the mainland, we’re trying to assert our autonomy under the auspices of one country, two systems. And, of course, the response to this is that even this word “autonomy” starts to get them in trouble because the question is whether they’re actually advocating for Hong Kong to become independent of the PRC. And there are a number of clashes around that.

When it comes to Covid-19 and US-China relations, this becomes very interesting. Given this new context of Chinese nationalism taking place on the Pacific Rim, the question is, okay, when it comes to anti-Asian hate, how should Chinese nationalists respond? They might protest white supremacy in very eloquent terms, but basically attribute it to [others] hating on Chinese people. There might be a new sort of victim narrative that emerges for Chinese people when it comes to US-China relations.

Or who will be dominant in the transpacific region, in light of recent events where there are strongmen on both sides of the Pacific? In this manly chest-beating, which nationalism wins? And that’s really scary to think about, but it sort of emerges from what I found too. Maybe some people are tired of being a sheet of scattered sand. Maybe the strongman is seen as the fantasy that emerges that unites the scattered sand.

Let me sort of play this out a little bit. I teach a course at my institution titled “Publics and Privates on the Pacific Rim,” and our first text is Die Hard. Die Hard is, in addition to being a Christmas movie, a Pacific Rim film. It’s about fake European terrorists in a truck called Pacific Courier, who invade a Japanese corporate building, the Nakatomi Plaza in Los Angeles. That’s the Pacific Rim. The response to this invasion is a sheet of scattered sand: the LAPD cannot figure out which department is in charge, the FBI gets involved, and suddenly the agents get involved with their kind of Vietnam War trauma, and they all kind of fall to pieces. But who will unite them? Bruce Willis. Bruce Willis is the strong man. And so one of the things that I say in the lecture that opens this class is sometimes this kind of scattering produces a strongman fantasy. Now, will the strongman actually be able to unite in an action movie? Yes. But is life an action movie? I get students to think about this. I think what we are seeing is maybe people are tired of the sheet of scattered sand. But turning to strongmen–is that is that actually going to work?

MB: It’s fascinating. Last question. What are you working on now? What’s your next project?

JT: I’m working on a couple of things. One, I’m co-authoring a book with my friend Xenia Chan. We presented a paper on what we are calling “transpacific counter poetics” and trying to tease out its relevance to political theology and the concepts of sovereignty and secularity. I’m also working on a project with my friend Ellen Zhou on Asian American evangelicals and what they post online and what that has to do with them narrating themselves as Asian from Asia and Asian American. I’m also developing an interest in transpacific coastal cities and climate anxiety. So stay tuned for that.