I’m old enough to remember going to Sunday evening services at my Baptist church growing up. Sunday mornings were the big event, of course, but Sunday evenings were for the die-hard church-goers, the hardcore Sabbatarians. Of course, it was a truism that church attendance was no sure indicator of eternal status. “Going to church doesn’t make you a Christian any more than sitting in a garage makes you a car.” At the same time, pastors emphasized church attendance was a necessity for disciples, since love for Christ’s bride was evidence of love for Christ himself. There was definitely an unspoken hierarchy of church members. The truly devout were the vacation-free, Wednesday-evening-and-twice-on-Sunday folks.

The American church landscape in 2024 is wildly different from the norms of my mid-90s evangelical upbringing. Digital media, generational gaps in wealth and labor patterns, demographic shifts, as well as social reckonings over racism, sexism, and predatory leaders, have made an impact on church attendance. The coronavirus pandemic proved to be a catalyst for speeding along changes that were already set in motion by decades of cultural shifts. As the numbers hit pastors’ desks week in and week out, it’s become clear that many church leaders are unsatisfied with the post-COVID religious world. Explanations for decline in church involvement vary. Jim Davis and Michael Graham’s recent book, The Great Dechurching, suggests a number of causes related to secularization, digitization, and politicization. Last Halloween, Trevin Wax published a piece offering his own hypothesis for the “great dechurching”: lazy Christians. Wax wrote that, rather than pointing the finger at church hurt or the increasing exposure of bad leaders, we evangelicals needed to look in the mirror. “I sympathize with those whose experience in the church has left them spiritually battered and bruised,” Wax wrote. “But most of today’s dechurching is the result of our wayward hearts, not church leader scandals. The human heart tends toward sin, and when we walk down a disobedient path, we’re inclined to rationalize our direction and decisions.” Dane Ortlund has repeatedly taken to X (Twitter) to decry poor or picky church attendees. Last summer, a video of JD Greear went viral when he called out those who came week in and week out but never engaged. And of course, over the last 25 years pastors have been engaged in a spiritual blood feud with traveling youth sports leagues.

It can be tempting to think recent poor church performance portends a long and steady decline in religious observance or group cohesion. The data over the last 5 years hasn’t exactly been encouraging. Pastors may find themselves longing for better days, for more faithful congregants, or more general investment in church life. The challenges of today’s church world have left many church leaders pining for “a New Reformation.” Looking to the past, we might see the energy of the young Reformers, the rigor of the Puritans, or the voluntary conversion of the Nonconformists, and assume the flame of church zeal burned brighter in those times. But a glance backward actually reveals something much more basic and, frankly, humorous. Evidence shows that church attendance was basically as frequent as social pressure or civil authorities demanded, which is no surprise. It also reveals that, basically, pastors have always complained about poor church attendance and low enthusiasm among their flocks. Literally from the time of the Reformation up to the present, church leaders have had higher standards for participation than do church attendees. And those leaders have been consistently disappointed when their congregants have failed to meet (or more often, utterly disregarded) the pastoral demands for frequent and consistent attendance. To illustrate this fact, I thought I might present a few vignettes from early Protestant history.

Early Modern Protestantism: A Period of Renewed Vitality?

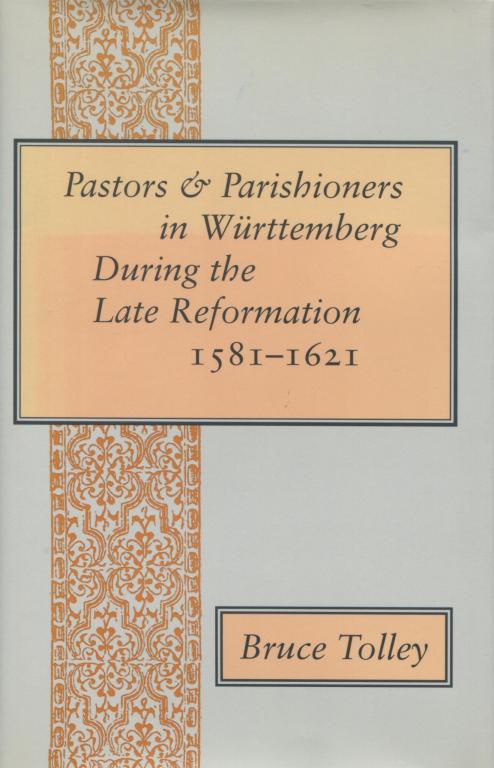

The Reformation—a time of fresh discovery, lay empowerment, biblical exposition, and renewed focus on the transformative power of the gospel. How hungry the people must have been for unmixed truth and spiritual worship! Well, whatever their hunger for truth, early modern parishioners’ appetite for programming was not exactly ravenous. And early modern pastors were not so unlike our own evangelical shepherds in their anxiety about participation, especially among young people. Bruce Tolley’s research on Württemberg church attendance between 1581 and 1621 reveals a religious community not so unlike our own. Using visitation records over a forty-year span, Tolley paints a vivid picture of the scene in Germany. Most townsfolk kept regular, if suboptimal, church attendance, which in the 1600s meant going to Sunday morning preaching. Even though the clergy offered numerous services, including weekday services and Sunday vespers, the pastors found attendance—and thus piety—lacking in some regard. As Tolley writes, “the common Württemberger apparently had little interest in attending Sunday services in the afternoon and evening or the weekday worship.” Especially unpopular were the catechesis services, intended for the education especially of youths and required by city ordinance. Children would be absent from catechesis because of family work or, in the summertime, because they were playing. One visiting pastor reported that in the summer the children of Tuttlingen “seldom come to sermons; they are out picking strawberries, similarly playing about the houses.” Tolley writes that poor attendance for the catechesis service was such a problem in this period that “it prompted a whole series of decrees and ordinances prohibiting Sunday afternoon fruit picking and dancing and strictly regulating the tending of livestock on Sundays.” Absentee church members almost always had good reason, at least in their own minds, for staying away—the inconvenient timing of services, the obligations of labor, or the allure of recreation.

people must have been for unmixed truth and spiritual worship! Well, whatever their hunger for truth, early modern parishioners’ appetite for programming was not exactly ravenous. And early modern pastors were not so unlike our own evangelical shepherds in their anxiety about participation, especially among young people. Bruce Tolley’s research on Württemberg church attendance between 1581 and 1621 reveals a religious community not so unlike our own. Using visitation records over a forty-year span, Tolley paints a vivid picture of the scene in Germany. Most townsfolk kept regular, if suboptimal, church attendance, which in the 1600s meant going to Sunday morning preaching. Even though the clergy offered numerous services, including weekday services and Sunday vespers, the pastors found attendance—and thus piety—lacking in some regard. As Tolley writes, “the common Württemberger apparently had little interest in attending Sunday services in the afternoon and evening or the weekday worship.” Especially unpopular were the catechesis services, intended for the education especially of youths and required by city ordinance. Children would be absent from catechesis because of family work or, in the summertime, because they were playing. One visiting pastor reported that in the summer the children of Tuttlingen “seldom come to sermons; they are out picking strawberries, similarly playing about the houses.” Tolley writes that poor attendance for the catechesis service was such a problem in this period that “it prompted a whole series of decrees and ordinances prohibiting Sunday afternoon fruit picking and dancing and strictly regulating the tending of livestock on Sundays.” Absentee church members almost always had good reason, at least in their own minds, for staying away—the inconvenient timing of services, the obligations of labor, or the allure of recreation.

So too in the rural towns around Basel, a major center of Reformation activity, pastors continued to lament their parishioners’ lack of regard for church services. Amy Nelson Burnett writes that even amid several edicts from the city authorities over a decade, church members flouted the civil ordinances. According to Nelson Burnett, rural pastors bemoaned Sunday morning hunters and women at the market before church, people plowing fields during the sermon, gossiping outside the church doors during the service, or coming in late. And even if they came to church, pastors complained that some parishioners came into service smelling of schnapps and falling asleep during the preaching! Nelson Burnett interprets the evidence of Basel’s church records to imply that when and where church attendance improved, it was due less to an uptick in piety than to strict enforcement of city edicts.

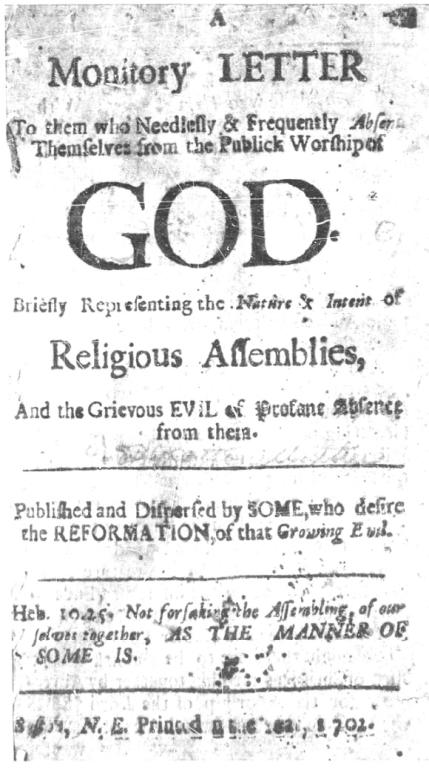

Anglican ministers similarly assessed the landscape of colonial Virginia in the 17th century. Jon Butler’s Awash in a Sea of Faith: Christianizing the American People, records minister Alexander Whitaker’s waning confidence in the piety of his Virginian would-be parishioners. Whitaker had become well-known for his praise of Virginian Christian morality in his 1613 sermon, Good News from Virginia, but according to Butler, by mid-century, “Whitaker complained bitterly about the lax Christian practice that continued despite his own energetic preaching and catechizing.” This was not uniformly the case, of course. Butler notes that the Massachusetts colony was particularly high in church affiliation and attendance, but even this early surge was challenged by second and third-generation Puritans, whose observance was sometimes quite spotty. (Roger Finke and Rodney Starke estimate that on the eve of the American Revolution, only 17% of colonists were religiously affiliated.) Certainly, in the eyes of Boston minister Cotton Mather, the lackluster attendance record of his fellow Congregationalists was a blight on the social organ as a whole. He wrote in his diary on May 23, 1702, that, while in prayer and asking God to increase his love of souls, Mather was inspired to write a pamphlet against the “destructive Impeity, wherein too many of this Town and Land indulged themselves; namely that of needless and frequent Absence from the religious Assemblies.” He cheekily remarked that since those indulgent ones were unlikely to be admonished in a sermon (since they wouldn’t be in attendance), a letter on the subject would be more useful. In fact, Mather’s address was one early example of a growing genre of early American pastoral literature, exhorting Christians to come to services early and often. One such pamphlet, published in 1785, warned that “the notorious profanation of the Christian sabbath by persons that call themselves Christians, either in unnecessary business or journeys, carnal pleasures or idle visits is a sad evidence of that infidelity and impiety which neither fear God nor regard man.”

Anglican ministers similarly assessed the landscape of colonial Virginia in the 17th century. Jon Butler’s Awash in a Sea of Faith: Christianizing the American People, records minister Alexander Whitaker’s waning confidence in the piety of his Virginian would-be parishioners. Whitaker had become well-known for his praise of Virginian Christian morality in his 1613 sermon, Good News from Virginia, but according to Butler, by mid-century, “Whitaker complained bitterly about the lax Christian practice that continued despite his own energetic preaching and catechizing.” This was not uniformly the case, of course. Butler notes that the Massachusetts colony was particularly high in church affiliation and attendance, but even this early surge was challenged by second and third-generation Puritans, whose observance was sometimes quite spotty. (Roger Finke and Rodney Starke estimate that on the eve of the American Revolution, only 17% of colonists were religiously affiliated.) Certainly, in the eyes of Boston minister Cotton Mather, the lackluster attendance record of his fellow Congregationalists was a blight on the social organ as a whole. He wrote in his diary on May 23, 1702, that, while in prayer and asking God to increase his love of souls, Mather was inspired to write a pamphlet against the “destructive Impeity, wherein too many of this Town and Land indulged themselves; namely that of needless and frequent Absence from the religious Assemblies.” He cheekily remarked that since those indulgent ones were unlikely to be admonished in a sermon (since they wouldn’t be in attendance), a letter on the subject would be more useful. In fact, Mather’s address was one early example of a growing genre of early American pastoral literature, exhorting Christians to come to services early and often. One such pamphlet, published in 1785, warned that “the notorious profanation of the Christian sabbath by persons that call themselves Christians, either in unnecessary business or journeys, carnal pleasures or idle visits is a sad evidence of that infidelity and impiety which neither fear God nor regard man.”

If Congregationalist ministers in Boston were concerned about religious laxity, English Baptist churches did not fare much better in the early 18th century. According to Ann Dunan-Page’s research, pastors of dissenting and nonconformist congregations in England faced the same headaches that established churches did. Sometimes people just didn’t come to church. A 1711 congregational report on absenteeism from a Baptist church in Cripplegate, London revealed that several members were abstaining from regular church attendance. One woman said she wanted to be in church but “having had a child lately & is excercised with it is not able to come[.]” Another, one Brother Grimes, claimed he “Went to hear Jos Jacobs on a subject in the Canticles on wch he has been ye 10 weeks & when he has don he will make good his place.” Sister Budephas said she and her husband were absent because “ye way is too farr,” and Sister Wood said similarly, “The reason she does not come in ye distance of ye way she had rather come but yet goes with her husband to hear Mr Pigott”. Weather, work, family, the allure of better preachers, recreation—all these were common reasons to stay away from church services. One church member of a Baptist church in Bampton, Oxfordshire, became the special object of pastor James Murch’s ire in 1707. Murch accused the man, Brother Morse, of sneaking out of the church’s business meetings, meetings that went on for hours, mind you. Morse, for his part, seems to have wearied of the church and its pastor. As Dunan-Page writes, “Morse at first pleaded the long distance that separated him from the regular meeting place of the church, but finally informed his fellow saints at Bampton that God had appeared to him to ask him to remove his membership elsewhere.”

Going to Church and Staying Home

Twenty-first century evangelical pastors face many of the same psychological stressors that early modern Protestant ministers faced. It can be easy to assume that, in the light of the “pure gospel” and under the zealous care of biblically-sound shepherds, Protestant churches in those early years were better off—more biblical, more pious, more invested. Yet, like our modern church leaders, early modern ministers were driven by a concern that their churches were slipping, that piety was in decline, that theirs was a uniquely dangerous cultural moment. And those trends carry through the postbellum period, American industrialization. Heck, even pastors in the 1950s were irked by frequent and numerous “stay-aways.” Maybe that’s a particular Protestant anxiety linked to an indulgent apocalypticism. Maybe it’s just human nature. But it turns out that people in those churches were a lot like us—people who valued church affiliation, who wanted to participate, and who sometimes had a lot going on. Similarly, it turns out pastors from Reformation Germany to Puritan New England were not unlike the church leaders of today—anxious to see an increase in holiness and reverence for the things of God which, perhaps inescapably, they measured by participation in church programming. The more things change, the more they stay the same.