In 362, Emperor Julian effectively banned Christians from teaching pagan texts, such as Homer’s Iliad and Virgil’s Aeneid, in an attempt to minimize Christian influence on the education system. In response, a number of Christians started to compose works in classical style during the 360s onwards, such as Gregory of Nyssa’s On the Soul and Resurrection, Apollinarius of Laodicea’s translation of the scriptures into Homeric Verse, and Prudentius’ Psychomania. If they were not allowed to teach these works, they would teach Christians in the style of the classics.

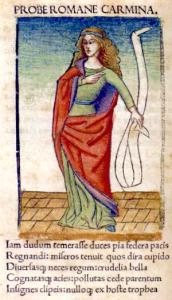

But there is one who joined their efforts, often overlooked in modern scholarship, who composed an innovative and massively influential poem which retells the storyline of the Scriptures in the words and style of Virgil: Faltonia Betitia Proba, perhaps the first Christian female poet.

Proba and her Virgilian Cento Concerning the Glory of Christ

Proba, as she calls herself in this poem (Cento, 12), was a Roman aristocratic woman from the mid fourth century. Her family, the Petronii, was filled with counsels and politicians, including her grandfather, Pompeius Probus; her father, Petronius Probianus; and her brother, Petronius Probinus. This family loved names that started with P, it seems! Proba married Clodius Celsinus Adelphus, who was the praefectus urbi of Rome (a position which oversees all the civil administration of the empire) and had two sons who became high imperial officers. In other words, politics ran in her blood.

Unfortunately, there is far more information about Proba’s family than about her own life. She does reveal that she wrote an earlier poem about war (Cento, 13-23), though she no longer thought this to be an appropriate topic—which has led to the assumption that she was a convert, with the former work being written before she became a Christian. In any case, all we can know with confidence of her is that she is a wealthy Roman Christian wife, mother, and writer.

The Virgilian Cento Concerning the Glory of Christ is a retelling of the Scriptural story. She begins with the creation of the world, walks through a handful of Old Testament stories leading up to the Flood, and writes a significant portion on Christ’s life, death, resurrection, and ascension. The style Proba wrote in is called a cento, which is: a “method of composition by which sentences and phrases are extracted from one or several texts and then put together in order to form a new text with a different meaning” (Cullhed, Proba the Prophet, 1). In other words, those who wrote centos pulled lines from classical authors—in particular Homer and Virgil—and placed them in a new order to form a new meaning. For example, she writes on the resurrection of Christ, exclusively borrowing lines from Virgil’s Aeneid:

| Line | Cento: English Translation | Cento: Latin | Line from Aeneid |

| 657 | Look, though! Beneath the eaves, the birds first twittering | Ecce autem primi | uolocrum sub culmine cantus | VI, 255; VIII, 456 |

| 658 | Quitting the hollow tomb, and exalted by its spoils | ingreditur linquens antrum | spoliisque superbus | VI, 157; VIII, 202 |

| 659 | He began to step upon his way and walk triumphant. And earth, enraptured, thrilled at the cadence of his feet. | Ibat ouans | pulsuque pedum tremit excita tellus | VI, 589; XII, 445 |

The English translation contains a striking image of the early morning resurrection—Christ reigns victorious over death, departing from the tomb. I am a particular fan of the line “And earth, enraptured, thrilled at the cadence of his feet!” Each line in the cento is actually drawn from two different lines of Virgil though (marked with the vertical bar), which you can see in the Latin original, with the corresponding passages in the Aeneid. While this reads straightforwardly as the resurrection in Proba’s Cento, the source material is mostly drawn from book six, which records Aeneas’ descent to the underworld.

The response of most critics throughout Christian history to Proba’s work has been less than positive. Jerome writes: “but we never think of calling the Christless Maro (Virgil) a Christian… [Cento writing] is puerile, and resembles the sleight-of-hand of a mountebank” (Jerome, Epistle 53.7). In the 20th century, the assessment is not much better. Dominic Comparetti, for instances, writes: “The ideas of such ‘Centos’ should only have arisen among people who had learnt Virgil mechanically and did not know of any better use to which to put all these verses with which they had loaded their brains” (Comparetti, Vergil in the Middle Ages, 53) Why are they so negative?

First, there is something a bit queasy about taking non-Christian stories and invocations to the Roman gods and applying them straightforwardly to the God of the Bible. As Elizabeth Clarke and Diane Hatch summarize, “Countless times Proba uses words characterizing Jupiter—Almighty, Sire, the Father—to refer to the Christian deity. Some of these are taken from singularly inappropriate contexts, as when Proba transforms the Virgilian tale of the male Heaven’s intercourse with the female earth to refer to God’s creative activity” (Clarke and Hatch, Golden Bough, Oaken Cross, 124). One might argue that the new meaning supersedes the old, and I am partially persuaded by this—Paul’s employment of the words of Greek poetry and philosophy in Acts 17 are straightforwardly applied to the Christian God. More striking, Luke’s record of Paul’s speech in the canonical scriptures means these pagan phrases are now divinely inspired, according to the tradition!

Second, because of its ‘patchwork’ composition, it never reads as beautifully as the epics from which it is derived. Importantly, this underappreciates how challenging it can be to pull together poetry that works in the content of the gospel story and matches the grammatical structures in the original language (Latin is a ‘gendered’ language). But, more importantly, this might misunderstand the purpose of Proba’s Cento. Is she trying to make an epic like the Aeneid? Or does she have another goal in mind?

Writing as a Mother and Aristocrat

Since Proba likely composed this work after Julian’s decree against Christian teachers, it seems likely that its purpose is pedagogical: she is using it as a teaching tool, especially for children. In the dedication to Arcadius, she asks him to “hand it down to the younger Arcadius |then he to his own sons. May your august | Posterity always receive this poem well | And teach it always to their families” (Cento, 13-15). Clarke and Hatch argue:

Proba’s Cento may have been a response both to Julian’s decree and to the larger question of education for Christian children. By piecing together lines of Virgil so that they sang of Christ rather than of arms, horses, and wars, Proba provided a pedagogic tool for such young people. Although we cannot prove the correctness of Amatucci’s judgement that Proba wrote the poem for her own offspring, we know with assurance that the Cento was widely used for educational purposes in Christian antiquity and the Middle Ages. Children could read Virgil, but Virgil so transformed that he sang “Christ’s sacred duties” (Clarke and Hatch, Golden Bough, Oaken Cross, 100).

The composition of this Cento, in a sense, fulfills the dual desires of a wealthy Christian Roman woman. Those educated in Rome started with Virgil, the bedrock on which all education stands. But Virgil is not exactly filled with stories for Christian homes and children. Thus, she can hold two supposedly competing notions together: her children can read Virgil, while learning about the God of the Scripture.

Her priorities as a mother come out in other places as well. She spends a significant portion of the work focusing on maternal themes, in particular on the infancy of Jesus. Proba provides a tender vision of Mary’s care for Christ after his birth: “And here, beneath the pitching, lowly roof, | She began to nurse her son, her full paps | Milking to his tender lips. Here, child, | Your cradle will be the first to pour | Out blossoms in profusion, just for you. (Cento, 375-377)

Proba’s role as mother bring out an aspect of the text that is sometimes obscured in the Gospel accounts. Unfortunately, she also obscures others though, on account of her wealthy standing. Throughout the work, all of Christ’s condemnations of wealth itself are scrubbed and replaced with denouncements of greed, likely because of her own riches. Take the account of the rich young ruler for instance. Rather than selling all of his possessions, Christ commands him: “Do learn, | O Lad, contempt for wealth, and also mold | Yourself as worthy even of God” (Cento, 522-523). Or, at the outset of the Sermon on the Mount, rather than “Blessed are the poor,” we have: “and, men, whatever wealth exists | For each of you, be glad, and call upon | your common God.” (Cento, 470-471). In other words, blessed are those who are thankful for what God has given you, whether you are poor or not.

A Different Picture

My earlier post on the Medieval Saxon Gospel discusses the ways in which we can obscure Christ’s commandments on the basis of our own priorities. Proba is, perhaps, an example of this, in masking Christ’s callings to renounce wealth. But, more positively, Proba demonstrates how diverse voices bring out unique dimensions to the text. In the fourth century, nearly every other ecclesiastical writer was male, somewhere in the church hierarchy, and at the very least praised celibacy and asceticism. Yet, in Proba’s poem, there is no praise of celibacy and asceticism at all. Proba is not exactly a representative of every Roman woman in this period, but in some ways—in being a wife and a mother—she has more in common with the average Christian than the ‘heroes’ of the day. In this sense, Proba’s Cento is a wonderful reminder of the power of mothers in shaping young people’s lives and finding creative and ambitious ways to follow Christ in that role—indeed, she is the first to employ this style for Christian ends. This church mother literally changed the church because of her maternal instincts. Perhaps, for this alone, we can echo Isidore of Seville’s praise of Proba: “Proba, wife of the proconsul Adelphius; a woman, and in this respect, she stands alone among the men of the church, because she busied herself with praising Christ, composing a cento about Christ fitted together with Virgilian verses. Although we do not admire her endeavour, we praise her ingenuity” (Isidore, On Famous Men, 136; Quote from Cullhed, Proba the Prophet, 20).

Resources:

Primary Sources:

Latin Original: Carolus Schenkl, Poetae Christiani Minores, Corpus Scriptorum Ecclesiasticorum Latinorum 16 (Vindobonae; F. Tempsky, 1888), 569-609.

English Translation: Elizabeth A. Clarke and Diane Hatch, The Golden Bough, the Oaken Cross: The Virgilian Cento of Faltonia Betitia Proba (Chico, CA: Scholars Press, 1981). Unfortunately, there is no easily accessible translation for this work.

Secondary Sources:

Elizabeth A. Clark and Diane Hatch, “Jesus as Hero in the Vergilian ‘Cento’ of Faltonia Betitia Proba,” Vergilius 27 (1981): 31–39.

R.P.H. Green, “Proba’s Cento: Its Date, Purpose, and Reception,” The Classical Quarterly 45, 2 (1995): 551-563.

Sigrid Schottenius Cullhed, Proba the Prophet: The Christian Virgilian Cento of Faltonia Betitia Proba (Leiden; Brill, 2015).

Virgil:

If you want to compare the Cento to Virgil’s Aeneid, here are some accessible websites with line numbers:

Latin Original: The Latin Library, P. Vergilivs Maro.

English Translation: James Rhoades, The Poems of Virgil (Chicago: William Benton, 1952).