I’m delighted to announce the publication of my new book, Kingdoms of This World: How Empires Have Made and Remade Religions (Baylor University Press, 2024).

Here is the catalog description:

Throughout history, the world’s great religions have been profoundly shaped by their encounters with successive empires. Secular empires have provided the means by which religions achieve their global scale, and any worthwhile historical account of those religions must reckon with that imperial dimension. In some cases, empires have favored and supported particular faiths, while in other instances they have suppressed traditions they feared or distrusted. Empires build cities and communication systems, they mix population groups from previously unconnected parts of the world, and crucially, they spread common languages. Taken together, such actions allow faiths to develop and spread, and eventually to achieve worldwide diffusion.

Kingdoms of This World is the first full-length study of the imperial contexts of the world’s religions. Philip Jenkins offers extensive coverage of Christianity, Buddhism, Islam, Judaism, Sikhism and other faiths, and ranges widely in tracing the imperial histories of many different parts of the world. This study also considers the religious consequences of the dissolution of empires in modern times. Drawing on the very extensive contemporary scholarship about empires, the book is an innovative and thoroughly researched survey of a critical topic in the history of religion.

In the modern era, we see that the main centers of the different faiths closely imitate the imperial maps of centuries past. Moreover, those religions inherit much from older empires in terms of their institutions, their art, and even their theologies. At so many points, we can see the ghosts of bygone empires in our own religious context. Kingdoms of This World gives voice to the interaction between religion and empire, providing a nuanced understanding of the past as well as its continual influence upon the present.

The book got some very nice endorsements, which I will include at the end of the present post. I am deeply grateful for these!

As I argue in my book’s opening chapter,

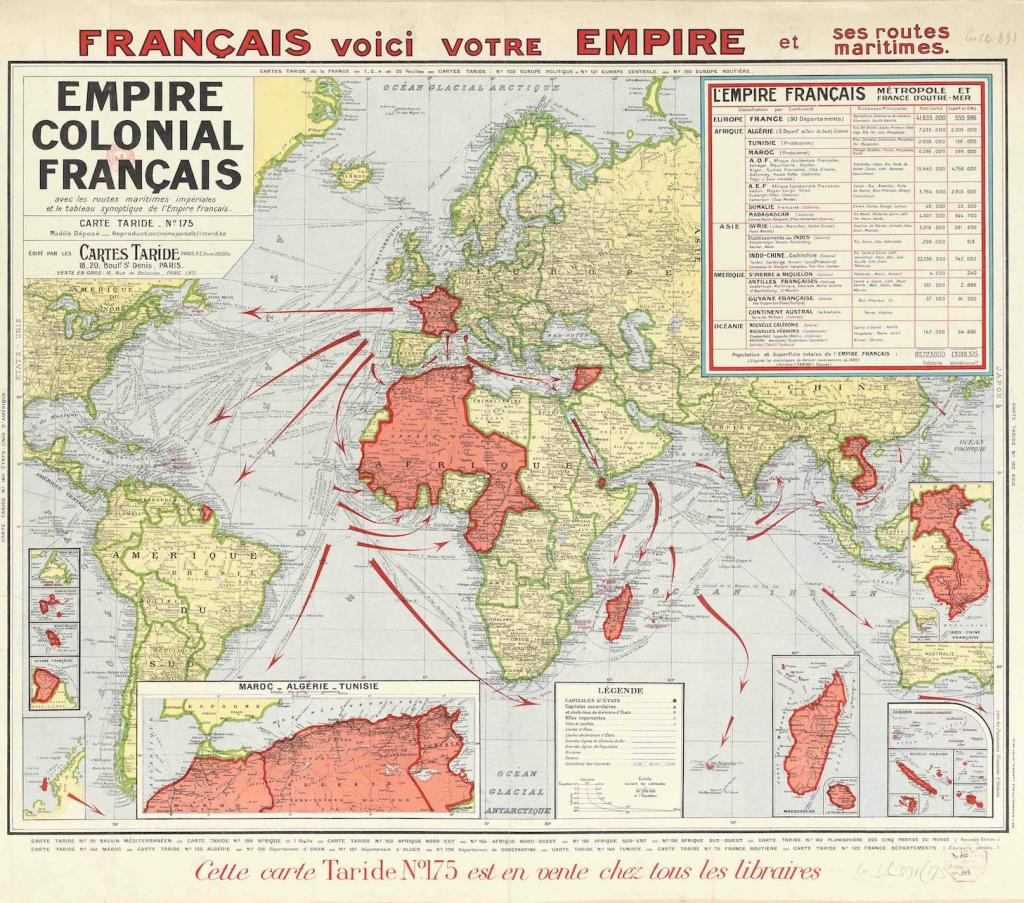

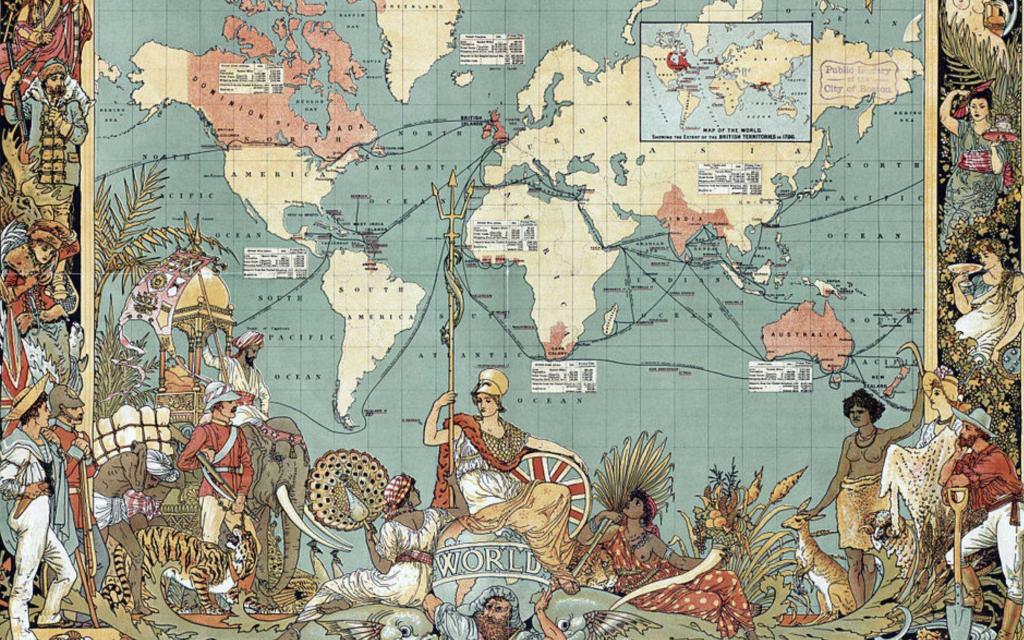

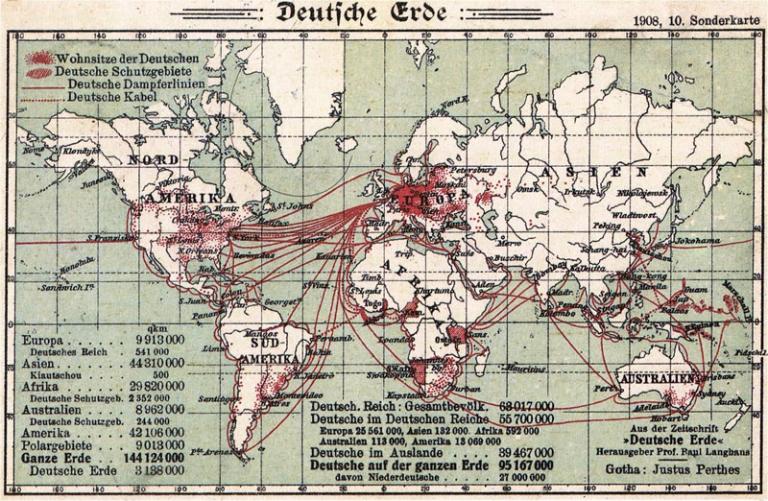

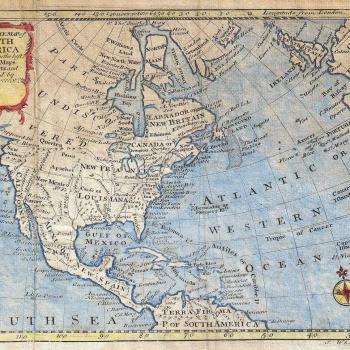

A map of Christian populations today indicates the persistence of multiple imperial ghosts. The great centers owe their origins to various Christian empires over the past half millennium: the Spanish, Portuguese, French, Belgian, British, and others. Within those empires, many people moved voluntarily, as settlers and colonists. Others were conquered or enslaved, and (at least initially) had new religious systems imposed upon them, although over time, those conquered peoples made the religion their own. Crudely, this is the story of how a religion that in 1500 was overwhelmingly Europe-centered became by the end of the millennium a vast transcontinental enterprise. The world’s largest Roman Catholic communities today are found in Brazil, Mexico, and the Philippines, recalling the influence of the long-defunct empires of Spain and Portugal. Soon, the Democratic Republic of Congo, the old Belgian Congo, will be counted among that elite of Catholic nations. The Anglican Communion likewise, with some ninety million believers worldwide, retains the unmistakable imprint of the old British Empire. In each case, such survivals go beyond the mere fact of geographical presence and are evident in the political traditions and structures of the respective religions, in their languages and forms of communication.

Although the papal analogies are not exact, the ecumenical patriarch of Constantinople is still first among equals in the hierarchy of the Orthodox Christian world. He is based in a city that has not had a significant Christian population since the 1950s but still retains the aura of the New Rome founded by the Roman emperor Constantine in the fourth century. The present incumbent is the 270th to hold the see. Other later realms have left their mark on Orthodox Christianity. Even today, after so much turmoil and persecution, the lands of the former Russian Empire still account for some 75 percent of the world’s Orthodox believers.

But such continuities are in no sense new and can in various ways be traced through the centuries. The Persian Empire left its spectral inheritance, as did various Islamic caliphates and the Ottoman realm, and so did several once-powerful empires in South and Southeast Asia. A map of the lands swiftly conquered by the Arab caliphate during its first century or so of existence—say, by 750 AD—gives an excellent (if not perfect) idea of the heartlands of Islam in the modern world, from Morocco to Pakistan, from the Caucasus to Yemen. Christianity, Islam, Buddhism, and Hinduism alike all reflect successive imperial encounters.

In some cases, the empires favored and promoted religious communities, while in others, populations and faiths were conditioned by reactions against intruding foreign powers, by what we might term “empire shock.” Much of modern Islamic history can be written in terms of the response to European imperial advances across Asia and Africa. By 1914, indeed, the overwhelming majority of the world’s Muslims lived under the rule of one or other of the European empires, and the destruction of the Ottoman Empire during the First World War threatened to reduce that independence still further. Modern political Islamism grew out of attempts to reconstruct the faith to respond to those successive traumas. Judaism, too, has been reshaped by encounters with successive imperial frameworks, whether benevolent or hostile.

Empires are an inescapable component in the making, remaking, and rethinking of the world’s faiths. To varying degrees, all those religions exist in what we might call a postimperial environment. A global history of the great faiths is of necessity an imperial history.

That is pretty self-explanatory, but I will just make a couple of additional points here. I stress that I am looking less at the decisions or actions of any given empire, but rather at the general factors that they share, what we might call their “empire-ness.” Regardless of ideology, empires have certain commonalities, sharing common languages, and so on – as I suggest in that cover description quoted above. I actually presented these ideas first in a column at this site a couple of years back, together with several other blogposts that sketched out my general arguments. You might in fact see this new book of mine as an Anxious Bench product!

Another theme that I first developed here is that of unintended consequences. When I say that a particular empire spread a given religious system, that sometimes means that authorities formed and implemented a plan. More commonly, those empires ended up achieving something utterly different from what they originally thought. When the Russian Empire built the great city of Odessa to dominate the Black Sea region, the faithful Orthodox Christians who ran the empire assuredly did not intend to create one of the world’s most thriving Jewish cities, but they did. When British rulers brought imported Indian labor to their far flung colonies in the Caribbean, East Africa, and elsewhere, they gave little thought to the fine job they were doing in spreading Hinduism and Islam. Other examples abound, from many different times and places.

Finally, I am delighted to say that this book avoids the trap of much writing on empire, which is to focus almost entirely on ancient Rome, and the more recent British empire, and to draw all the examples and quotes that offer such low hanging fruit. Kingdoms Of This World really is very wide ranging, with (among other things) lots of Russian, Dutch, and French material.

ENDORSEMENTS FOR KINGDOMS OF THIS WORLD

There is no scholar of religion writing today who has more of a right to say that the world is his parish than Philip Jenkins. Kingdoms of This World ranges dazzlingly across the centuries, the continents, and the major religions. The result is not only insightful, but breathtaking.

~Timothy Larsen, author of The Slain God: Anthropologists and the Christian Faith

With trademark magisterial mastery of world history, Philip Jenkins offers a sweeping view of the mutual impact between empire-building and the making of religions. While much has been written on the collusion between Christianity and empires, Kingdoms of This World expands scholarship by examining other religions such as Hinduism, Buddhism, and Islam, and shows not only how empires have made and remade religions but also how religions resisted empires. A significant addition to empire literature.

~Peter C. Phan, The Ignacio Ellacuria, SJ Chair of Catholic Social Thought, Georgetown University

If polite conversations should avoid both religion and politics, Philip Jenkins has upset convention to show, in a luminous account, the deep inner connections between politics at its broadest (empire) and almost everything having to do with faith. Although the book includes captivating discussion of Hindu, Buddhist, and Muslim empires, it features even more perceptive consideration of Christianity and empire (as in one brilliant example: ‘The Palestine of Jesus’ day was a palimpsest of empires, past and present’). Kingdoms of This World is a wide-ranging but always lucid examination of a reality as vast as it is important.

~Mark Noll, author of America’s Book: The Rise and Decline of a Bible Civilization, 1794-1911

Empires have been the default setting of political organization throughout the ages. As such, their history is interwoven with the formation and expansion of the world’s great religions in intricate and ambiguous patterns. Philip Jenkins’ book, founded on an extraordinary range of reading, uncovers those patterns with rare insight and comprehensiveness. This work demands the attention of scholars of both religion and imperialism, and of all those who wish to understand the religious and ideological contours of the modern world.

~Brian Stanley, Professor Emeritus of World Christianity, University of Edinburgh

When in a previous generation the British historian Arnold Toynbee wrote A Study of History to review the rise and fall of empires, he became increasingly convinced that religion formed a key to understanding the process. Now he has a successor, Philip Jenkins, who in this book analyzes the ways in which world faiths have related to successive empires. Jenkins, however, is much more convincing than his predecessor because he builds on the extensive work of many recent scholars. The result is a magisterial overview of the interactions of empire and religion in recorded history.

~David Bebbington, Emeritus Professor of History, University of Stirling

Kingdoms of This World covers a stunningly broad scope of religions and empires to demonstrate the tragic and interdependent relationships between them. This is an ideal model of scholarship in the global history of religions.

~Thomas S. Kidd, Research Professor of Church History, Midwestern Baptist Theological Seminary

Drawing on deep wells of learning, Philip Jenkins addresses a notable gap in the literature of the history of religions: a synoptic overview of the interrelations between religion and empire. Jenkins illuminates the changing fortunes of various religions by showing how they were shaped by their imperial matrices. In a book of great geographical and chronological span Jenkins draws telling comparisons and contrasts between the religions of the East and West. Kingdoms of this World: How Empires Have Made and Remade Religions provides a new vantage point for understanding religions as a global phenomenon.

~John Gascoigne, Professor Emeritus, University of New South Wales