“People without hope not only don’t write novels, but what is more to the point, they don’t read them. They don’t take long looks at anything, because they lack the courage. The way to despair is to refuse to have any kind of experience, and the novel, of course, is a way to have experience” (Flannery O’Connor, Mystery and Manners, 78).

I can still remember the thrill of starting my first classes at Fuller Theological Seminary. I never really drove into Pasadena before, so it was a brand new experience (there is always freeway traffic to prepare for anywhere you drive in Southern California, but driving through the heart of LA, on the 110, is another matter altogether). At the time, I was obsessed with Karl Barth, and managed to take a Barth seminar in my first semester because I spent my last two years at Biola University researching his work. I loved the Barth class and would inevitably work on my dissertation about the Swiss theologian. As much fun as I was having in that course, it was my first systematic theology class that was really exciting.

Dr. Veli-Matti Kärkkäinen was the professor. What I loved about the class was the focus on major theologians from across the Christian denominational divide. Dr. Kärkkäinen taught with charity and charm, allowing us the freedom to look anew at the way some theologian from a different tradition understood Christian theology. His classes opened up the reality of global Christianity. The theologian in the past century who may have recognized this dimension the best is Jürgen Moltmann, who recently passed away.

Moltmann was often paired with the other eschatology fellow, Wolfhart Pannenberg. Both are obviously brilliant and if memory serves me correctly, Dr. Kärkkäinen tended to include them in about every doctrinal topic. Because of this first semester, I sought out books by both German theologians. What exactly drew me to read them? In fact, even though I bought books by both, if I am being completely transparent, I mostly read Moltmann’s books.

First, I found Moltmann a pleasure to read. These books were packed with deep discussions about theology, history, and philosophy but in a way that was impactful for me, someone who grew up in a Christian home, attended Christian school and then college. I craved that dual dimension of heart and mind—theology and praxis, and Moltmann’s books were just what I needed at the time (especially for someone who was lost in the catacombs of Barth’s voluminous works).

Second, Moltmann anticipated where Christian theology was headed after WWII. Without debating fifty-plus years of Christian history, he was ahead of the curve when it came to the following issues: Jewish-Christian dialogue and Post-Holocaust theology, the environment, the continuing rise of Pentecostalism, various forms of contextual and liberation theologies. I am not a Moltmann expert but what I have gleaned from my reading is that he usually handled his topics in a non-condescending type of way with an openness and willingness to learn from others especially those historically harmed.

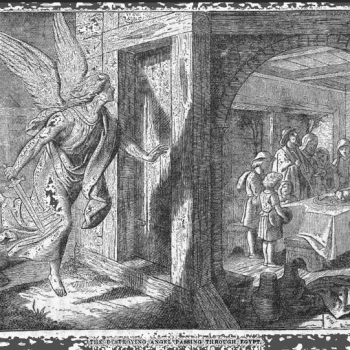

Moltmann’s first book was The Theology of Hope and that label would define him for the rest of his life. Hope seems like such a silly notion in light of the horrors of history. But that is Moltmann’s point about Christ’s entrance in history. His death and resurrection changes everything—we should do theology like that is true. Moltmann, who learned much from Barth, in some ways, updates Barth’s theology for the post-Holocaust, Cold War era.

It is rare to witness the passing of a theological giant. For all his world wide fame, I know he was a wonderful mentor to many students. The work of Patrick Oden being just one example of influence. In fact, Oden’s recent book, which includes Moltmann’s Foreword, might be the type of message of reconciliation we need at the moment.

Perhaps our presentism has gotten the best of us. I expect in some non-Christian circles to see declarations about the current state of affairs with a cool, skeptical, often cynical distance. But from the church? Where is the blessed hope? The frequent turn toward presentist doomsday talk betrays a key aspect of Christian eschatology and thus belittles the tragedy of history in the past. Was life any less terrible right after WWII?

Taking a cue from Flannery O’Connor, being hopeless sucks the imagination right out of us, devoid of human and divine experience. How does one really write or even read without a sense of hope? O’Connor may be talking about fiction in her quote, but, thanks to Jonathan Franzen’s essay “Why Bother” where I found this quote, this idea can be applied to any literature or activity that provides meaning. I appreciate Moltmann’s work because he stared directly into the abyss of human depravity that lingered after WWII, but refused to give up on hope. His reading of the biblical narrative shaped his view of history — where it has been and where it is going. He saw the renewed focus on the Holy Spirit as an act of God in our times as a guide that God is, in fact, still with us.

I remember thinking in some instances that Moltmann’s imagination led him to get carried away with his theological speculation—being so concerned about praxis may have thrown off his orthodoxy in some places. Again, being completely honest, it has been a while since I have read any of his recent books. The big immediate history question will be: will future generations read Moltmann? Like Barth, I think they will because of how they redirected Christian theology. The thought that comes to mind about Moltmann is that he did not try to explain away the mystery of Christianity. He retold the narrative of Christian theology after WWII as a global conversation-partner.

One of the most powerful images that captures Moltmann’s legacy is a bloody symbol left after the massacre of Salvadoran priests (I wrote about this in my book) in the late eighties.

Even in this most tragic, disquieting moment, Moltmann’s blood drenched book managed to symbolize that God through Christ identifies with the victims and that their martyrdom would inspire to continue to hope and imagine for a better world. These are the types of lessons I learned in Pasadena over a decade ago.