This is my first piece as a regular columnist for the Anxious Bench, and I’m going to deviate a bit from most of what I have written thus far for this blog. About a year ago “the crisis of masculinity” became the problem of American society—the discourse™ became centered on the question of masculinity in America. There were a series of articles, videos, and news reels wrestling with the problem of men. One such piece happened to quote me about the crisis. I was asked by several people at the time what my own thoughts on masculinity were. I pushed such a project off for a while, letting it percolate. After many conversations, much thought, and rewatching several movies; this piece is the beginnings of a thought on the matter.

This is my first piece as a regular columnist for the Anxious Bench, and I’m going to deviate a bit from most of what I have written thus far for this blog. About a year ago “the crisis of masculinity” became the problem of American society—the discourse™ became centered on the question of masculinity in America. There were a series of articles, videos, and news reels wrestling with the problem of men. One such piece happened to quote me about the crisis. I was asked by several people at the time what my own thoughts on masculinity were. I pushed such a project off for a while, letting it percolate. After many conversations, much thought, and rewatching several movies; this piece is the beginnings of a thought on the matter.

Almost everyone has agreed for a while that masculinity is in crisis. I won’t take time here to argue for the existence of this crisis. Instead, I’m going to try and give a positive vision of masculinity in an American context. To do so, I will invoke characters from several important Westerns produced during the Cold War, whence, it might be argued our current crises stem. The most famous dueling Westerns from this period may well be High Noon starring Gary Cooper, directed by Fred Zinneman, and the John Wayne and Howard Hawks trilogy of Rio Bravo, El Dorado, and Rio Lobo. Hawks and Wayne saw High Noon as dangerously anti-American and perhaps sympathetic to communism. They both worked publicly to have film’s writer and director blacklisted in Hollywood and made their own films to represent a different story of the heroic American lawman. If you aren’t familiar with that conflict, I recommend reading up on it.

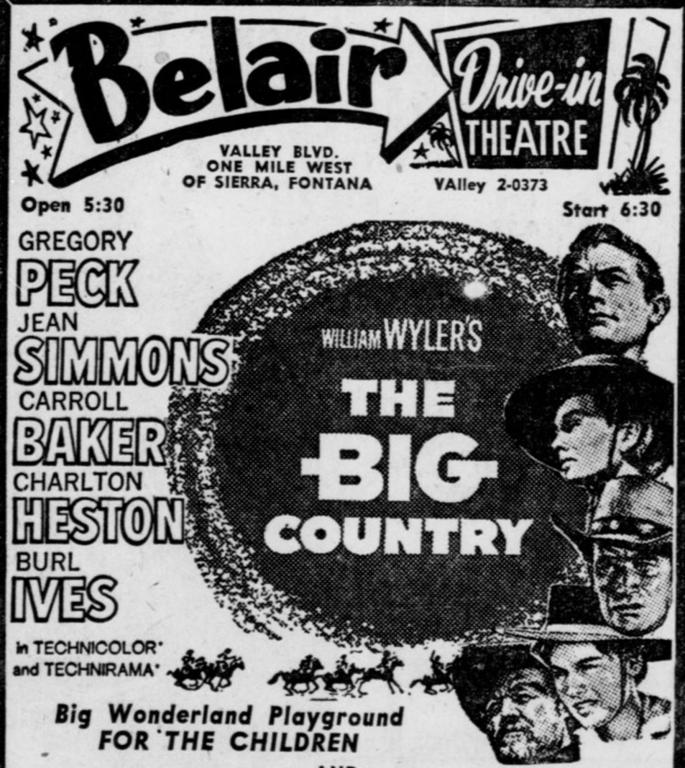

I only mention the conflict here as a precedent for dueling masculine archetypes I see in another remarkable Western from the period. The Big Country (1958), was written and directed by William Wyler, and was his project directly before the legendary Ben-Hur. I think it offers us a set of character studies in American masculinity that help us find both some diagnoses and perhaps a way forward. In The Big Country, we follow Gregory Peck’s Jim McKay—a college educated sea captain and heir to a shipping empire. As the film opens, McKay is engaged to Pat Terrill, played by Carroll Baker. Pat is the daughter of Maj. Terrill (Charles Bickford), owner of the largest ranch and ruling elite of the region.

The Big Country is, as far as I can tell, an under-remembered film. I only happened upon it because I bought its two-tape VHS when a video rental store in my small Georgia hometown was going out of business. The film attracted me because I enjoyed Westerns; plus, Gregory Peck and Charleton Heston were on the front—what more could a boy want? A first viewing around age nine found the film to be tedious and lacking sufficient gun fights. Without streaming at my fingertips though, I often rewatched films, and over time, The Big Country became one of my favorites. I probably watched it a dozen times before leaving for college and largely forgetting it. Occasionally, it would pop up in my consciousness, but I didn’t rewatch it again until grad school amidst the COVID pandemic. Suddenly, the film stood before me powerfully, in an altogether different light. The film now presented me with four visions of white masculinity in America competing for my support, arguing that I should emulate them. The movie is almost seventy years old, I apologize for spoilers, but regardless, I recommend checking it out on Amazon Prime.

The first character we meet is a stranger in the land, stepping fresh out of a stagecoach. Gregory Peck plays Jim McKay, remarkably out of place in his dude suit and bowler hat amidst the clearly still wild West. We are given the impression—although it’s never explicitly stated—that he has sailed around the globe at least once. He knows how to plot a course with map and compass. He’s worldly, with a strange bit of old-world flair about him and a particular sense of quiet justice that makes his more macho interlocutors uncomfortable to say the least.

Contrasted with McKay are two feuding Western patriarchs and their followers. Major Henry Terrill (Charles Bickford) is the father of Jim’s fiancé and owns the largest ranch in the region. There are several reasons to think that his rank comes from serving in the Confederate army during the Civil War. Opposing the Major (as he is called throughout the film) is Burl Ives as Rufus Hannassey, in a role for which he won the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor. Hannassey is the father of a rowdy family that while rich in land, lacks money and a consistent water supply. Each of these men has their own protégé: Charlton Heston’s Steve Leech is the Major’s ranch foreman who was also raised by him; Buck, played by Chuck Connors, is Rufus’s eldest son—a hard drinking, hard riding man that his father fears is a coward. Rounding out the cast are Carroll Baker as the Major’s daughter and McKay’s fiancée and Jean Simmons as Julie Maragon, a schoolteacher and heiress to the third of the largest ranches alongside the Hannassey’s and Terrill’s.

Three moments stuck out to me when re-watching the movie with these questions surrounding American masculinity on my mind. The first comes when Steve Leech attempts to convince McKay to ride an older wild horse kept around to embarrass newcomers. McKay refuses to ride the horse in front of a waiting audience, telling Leech he will do so another time. He does in fact ride the horse later, alone except for the assistance of a Mexican friend named Ramone. The Major attempts to explain this attempt to Jim as a rite of passage. While Jim acknowledges the helpfulness of such moments, he explains how he underwent such rituals “at college, and when I first passed the equator, I was keelhauled.” The Major makes clear that having participated in these rites of manhood mean little to nothing in the new culture he has come to live amongst. He explains how he has raised Steve Leech from a young man who arrived with only the clothes on his back to be the best foreman in the country. Later, this moment of conflict is brought to a point when McKay returns from a couple of days of solo travel, only to be accused (again) by Leech of being lost and too cowardly to admit this. On the contrary, Jim has been navigating with his own map and compass, a skill the cowboys and their master lack. So while it is beyond their imagination that any stranger could travel across the plains without getting lost, Jim had no problem. Again, McKay refuses to perform before an audience. Recognizing that Leech is picking a fight, Peck’s character calls out his motives: earning the admiration and perhaps love of McKay’s fiancé. Later he invites Leech to a fight, only asking that “whatever happens, let’s keep this between us.” After a drawn out, torturous fight, the combatants are left similarly exhausted and seemingly unmoved.

The second of these moments comes as Pat Terrill talks with Julie about her distrust of Jim that has grown since he refuses to fight (ostensibly for her) or even ride Old Thunder, the wild horse. Julie knows from a conversation with Jim that he did ride the horse and finds Ramone to ask for confirmation. Ramone refuses to answer Patricia when she asks, but Julie is able to wheedle the information from him. Patricia is aghast that Jim would ride the horse without an audience and expresses confusion as to what the point of such an exercise would be. Julie tries to explain that Jim is not interested in demonstrating his masculinity for anyone. This isn’t a sign of cowardice or a lack of ability, but rather a fear “that anyone might think he’s showing off.”

Finally, the film ends with two one-on-one duels instead of the large-scale fight that both patriarchs claim to desire. The first is between Jim and Buck Hannassey. The former is finally forced to fight publicly because Julie is being held hostage to try and gain control of her ranch and ensure water rights for the Hannasseys. Rufus requires them to use the dueling pistols Jim inherited from his father. Here we see two important conflicts come to a head. Earlier, Julie informs Jim that the whole country has been waiting for the moment when Leech and Buck confront each other—each as the champion of their mentor’s way of being in the Big Country. Instead, Jim confronts both of them, keeping the peace as he told Julie he hopes to. Simultaneously, the duel with Buck forces a dismayed Hannassey to seek out a final confrontation with the Major, telling Jim, “This is between the Major and me.” Hannassey calls out the Major to meet him in canyon, man to man so that no one else has to die. The two shoot each other and collapse at each other’s feet. Of the main characters, only Jim and Julie remain to inherit The Big Country. They ride back to their ranch with the populist and elite sides of the feud lying shattered and dying.

They have no words. As viewers, we could remain silent. So many words have failed to get far beyond diagnosis. Perhaps if we just wait for the many-headed hydra of toxic masculinity to die out, things will get better. I don’t think we have this luxury. And not only because no generation of young boys deserves to suffer the emotional neutering that both Steve Leech and Buck Hannassey undergo. What might a healthy vision of masculinity along the lines of that practiced by McKay look like in our day?

I want to argue that masculinity when healthy is a type of authority: power tempered by the relationships which demand something of us as lived particularly by men. Masculinity, properly, lies at an intersection between two virtues: magnanimity and prudence. In The Big Country, Jim McKay exemplifies the tension that is a virtuous masculinity. He is strong and has undergone his own group’s rites of manhood, and thus is able to reject what Leech and the Major want to require of him. He can properly assess and then ignore their attempts to attack his character and bearing. Despite arriving as a fish out of water, Jim quickly shows he has authority, without seeking personal glory or recognition. He exercises prudence, by not performing the exercises in machismo desired, but still shows himself capable of them at times and places of his own choosing. In contrast to the macho posturing and bravado of other male characters in the film, McKay’s masculinity is defined by his inner strength, moral courage, and capacity for empathy. He embodies a different kind of heroism—one that transcends (without diminishing) physical prowess and instead emphasizes moral integrity and compassion.

One of my favorite writers on this problem in America has this to say: “I want there to be a place in the world where people can engage in one another’s differences in a way that is redemptive, full of hope and possibility. Not this ‘In order to love you, I must make you something else.’ That’s what domination is all about, that in order to be close to you, I must possess you, remake and recast you.” How do we create a space for the creation of adulthood in general and manhood in particular that is not dependent upon domination of an other? Three moments from my growing up standout to me in considering this.

First, when I turned thirteen, my parents did something I find increasingly remarkable. They asked around a dozen men in my life from all sorts of backgrounds to write me letters about what it means to become a man and particularly, a Godly man. I still have these letters and read them at least once a year. Even when I no longer agree with their advice, I find wisdom that directs me. I found this process so meaningful and shaping, that when I recently turned 30, I asked several mentors to write me similar letters for thinking about being a man in the next stage of life. This points towards two things I think boys growing up right now need. First, they need male role models to spend time around. Studies show that boys need men in their lives in order to mature healthily. I made this point in the Washington Post article last year, but I think it remains incredibly important. Most of the boys and young men I know don’t want or expect someone flashy. They just want older men to spend time with and learn from. A moment particularly sticks out to me from soon after my dad died. I met one of my pastors for coffee and then, he brought me along grocery shopping. I was invited into his and his family’s life. This was huge. Since then, I have had other men invite me in similarly, and whether it was Scotch whisky, landscaping, religious history, political psychology, or kitchen repairs, I learned as much from simply being around these men as I did skills.

Second, and related to the letters I received; rituals of transition are important. I’m not saying everyone should have the same goal as my mother, who wanted me to be capable of taking care of a house by age thirteen. However, I think the fact that I learned to cook, clean, do laundry and iron, balance a checkbook, alongside the outdoors skills I was learning in Boy Scouts, helped me feel I had the ability to be an adult—even a man. Not only so, but these rites or rituals should be recognized across the different forms of our society. It won’t look the same in the South or rural Midwest as it might in New England or the Pacific Northwest. As the disagreement between Steve Leech and Jim McKay show, when we fail to recognize a common manhood achieved different ways, we are inviting not just conflict, but violent conflict. One method of doing this, which I will only gesture at is mandatory (non-military) national service. This is obviously a controversial subject, but one remarkable possibility it represents is a universal baseline for adulthood across the country. It would also create an opportunity for the understanding of different types of coming into adulthood that I have gestured towards. What is most important is not the particular method by which this occurs, but that a community, including adults (especially older men) provide it for boys as they are brought into maturity.

As I hope these two points demonstrate, we cannot have healthy men without healthy communities and mentorship practices. This is also a lesson from The Big Country. Neither the feuding Terrill nor Hennessy families creates the community necessary for healthy men to be formed. This leaves us in an uncomfortable position. I remain unconvinced that we have communities healthy enough to grow children into generic adulthood, let alone manhood and womanhood. This also implies we are unable to foster a healthy environment for any sort of romantic relationship. We are already unable to recognize any shared humanity in those we vehemently disagree with, let alone a common manhood. We cannot hope for a top-down solution. No one is going to hand us communities that create healthy, small-scale relationships, but we may be able to build them in the homes and communities where we already live. I have found myself over the last few years talking with young men from an immense range of backgrounds, family lives, and stories discussing the loneliness we feel and how we might be men. If you make yourself available and approachable you might also find yourself addressing this problem at the granular scale wherever you are.