I have been working on the religious dimensions of American empire, and particularly some of the unintended consequences of that story. We all know about empires sponsoring missions among conquered peoples, but on occasion ideas spread from colonized and subjugated peoples to infiltrate the metropolis, where they might even establish a kind of spiritual bridgehead. I have mentioned this in the context of the New Age and esoteric ideas as they developed during the twentieth century.

Native Prophets

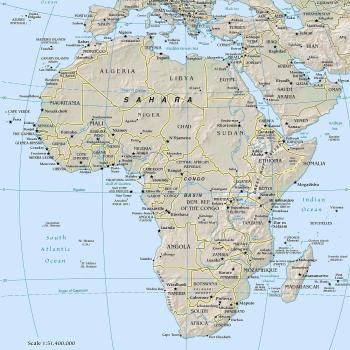

Spreading official faiths can also mean giving conquered peoples access to subversive aspects of those faiths, or rather, to aspects that we had not even thought of as subversive up to that point. In some cases (as in colonial Africa) that led to religious-based resistance movements. One key figure in the history of anti-colonial resistance was John Chilembwe who in 1915 led a potent revolt in British Nyasaland (Malawi). Chilembwe attended a historically black institution in Lynchburg, VA, where he acquired Black nationalist ideas, fortified by radical religious doctrines. He drew heavily on Baptist apocalyptic thought, with an added dose of America’s emerging Watch Tower movement, which had identified 1914 as the year of Armageddon.

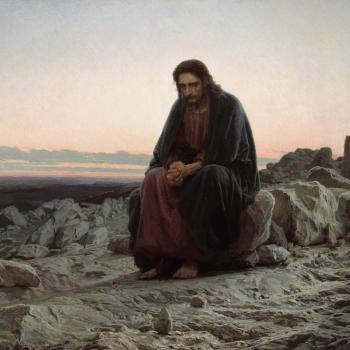

Often through history, such subversive converts claimed to enjoy special prophetic or visionary powers in their own right. The movements they led have been remarkably common through the centuries. Visionary prophets and messiahs were a frequent occurrence in medieval Europe, while similar stories have erupted regularly in the Global South during the process of Christianization. Arguably, such charismatic prophets are an inevitable by-product of the conversion process, and their appearance in large numbers marks the transition from a grudging and formal acceptance of Christianity to the widespread internalization of Christian belief among the common people. In a sense, this is how Christianity goes native.

There is a long history of Native American peoples coming into some contact with Christianity, and selectively adopting some of its ideas in this way. The exact nature of such influence is always open to debate, and we are never entirely sure whether given Indian “prophets” were drawing more on Native or imported ideas. But some kind of influence is certain. If specific ideas were not borrowed, general themes were, including messianic dreams and prophetic visions, End Times visions of resurrection and renewal, and millenarian expectations. Depending on the era, such influences might originally derive from any number of familiar American movements, including Adventists, Mormons, Pentecostals, and others. What was thoroughly mainstream and even conservative in one context acquired very different connotations in the new leaders.

Such for instance was the Seneca Handsome Lake (Ganyodaiyo’) (1735-1815) who struggled to reverse the moral and cultural disintegration that the Iroquois people were suffering following repeated defeats. He taught an elaborate moral code that among other things prohibited liquor, and his cultural reformation made his people stronger and more stubborn foes of American expansion. Anthony F. C. Wallace’s classic book on the era has the significant title The Death and Rebirth of the Seneca. We can certainly see some Christian influences there, notably from the Quakers.

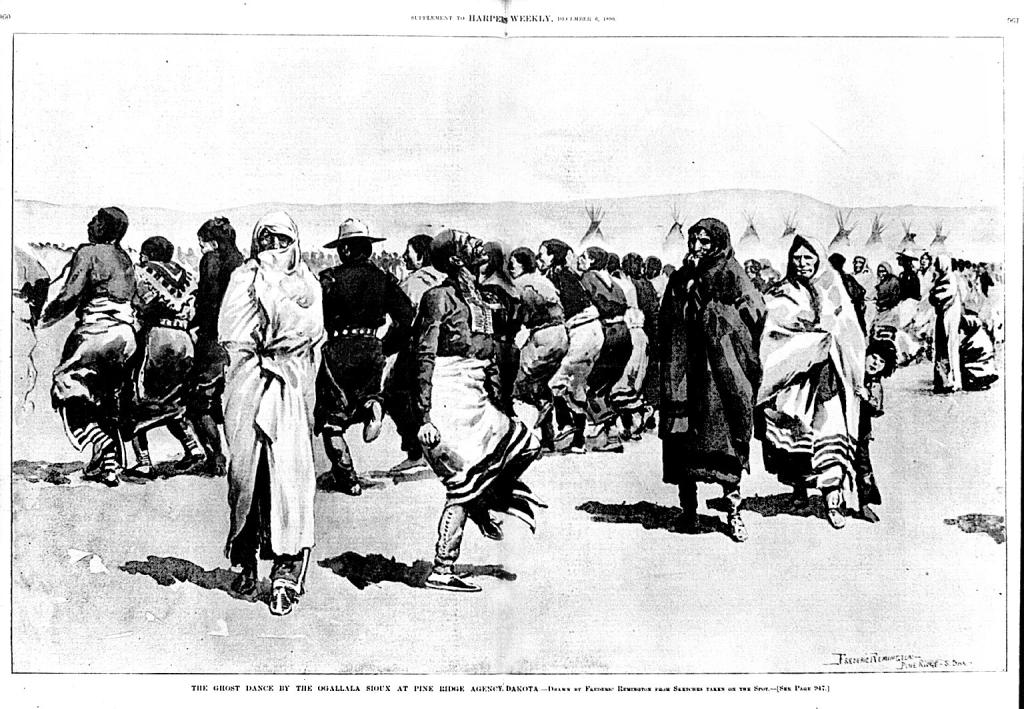

Handsome Lake had several counterparts. Smohalla (1815-95) was an influential dreamer-prophet in the Pacific Northwest, who may have taken the idea of human prophets declaring messages from heaven from what he witnessed of Mormon practice. Smohalla established a whole religious system, together with other prophets. The Christian component was obvious in the Paiute Wovoka (1856-1932), who created what white Americans called the Ghost Dance religion. Under strong evangelical influence, Wovoka preached about Jesus Christ, and warned of a Judgment Day at which the Native dead would rise. Depending on interpretations, some versions of the religion also told that white people would vanish, as the buffalo returned. The messianic expectations that now surged led to a conflict with US forces, and culminated in the Wounded Knee massacre of 1890.

For the relationship between the Shakers and a key Native prophetic figure, see now Douglas Winiarski, “Revisioning the Shawnee Prophet: Revitalization Movements, Religious Studies, and the Ontological Turn,” Early American Studies: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 22(2)(2024): 305-350. I am grateful to Wyatt Reynolds for drawing this important study to my attention!

Mr. Stevens’s Pupil

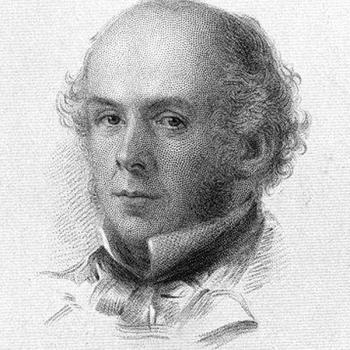

I sometimes argue, tongue very much in cheek, that the most influential single figure in American religious history was not Jonathan Edwards or Billy Graham, but rather the Connecticut-born Congregationalist missionary Edwin Stevens (1802-37). How on earth do I justify such an outrageous claim? Well, Stevens was an early missionary to Qing imperial China, based in Guangzhou (Canton) and as I will explain, that setting is vital. From early times, Guangzhou was the pivot of American hopes of establishing an Asian presence like that of the British in India. It was the heart of American imperial dreams, at first commercial, but later… who knew? Might it become an American counterpart to imperial British Calcutta? (I am here using Dael A. Norwood, Trading Freedom: How Trade with China Defined Early America (University of Chicago Press, 2022).

“In 1784, the first American trade ship, The Empress of China, arrived on the shores of Canton, raising the U.S. flag for the first time in China. Canton is also where Congress sent the first U.S. diplomat to China in 1786.” Among other goods, The Empress of China brought ginseng to trade for Chinese black tea and silk. Lavish profits encouraged other merchants, and both Providence and Baltimore boomed from the Chinese market. Under the booming “Canton system,” all trade was required to be organized through Chinese intermediary merchants, the hong, while Americans were confined to their Golden Ghetto. Gradually, Americans also ventured into the illegal opium trade, which channeled terrific wealth home to New England, and enriched several Boston brahmin houses. One of the greatest was the Delanos – you know, as in Franklin Delano Roosevelt, their descendant. Americans probably controlled ten percent of the commerce (the British had the rest). By 1844, Guangzhou was one of the five Treaty ports where American and other Western merchants could trade freely.

Missions followed trade. The first two Americans arrived in Guangzhou in 1830, sent by the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, the ABCFM. Two years later, they were joined by Edwin Stevens, who was hired as a chaplain. That Guangzhou operation became the hub for all the early Protestant missions across China and beyond. I like the subtitle of John R. Haddad’s book on this era, America’s First Adventure in China: Trade, Treaties, Opium and Salvation (Temple University Press, 2013). The ABCFM hoped to bring Salvation, but results were mixed.

Around 1836, Stevens and his colleague Liang Fa got the bright idea of evangelizing candidates taking the famous civil service examinations that gave them admission into the ruling elite. Ideally, this would win Christian converts at an early stage of their careers. One of the works Stevens regularly handed out was Liang Fa’s Good Words to Admonish the Age, and in Guangzhou he duly gave one to a very unhappy candidate named Hong Xiuquan, who had just scored his embarrassing second failure in the exams.

So why on earth should Stevens’ act be so important? Because Hong was so influenced by this pious sketch of Christian doctrine that it thoroughly shaped his life and thinking. He now experienced a visionary ascent to heaven, where he met his true family, which included God, the Virgin Mary, and his elder brother, Jesus. His prophetic mission to redeem China was institutionalized in a new Society of Worshippers of Shang-ti (God), which launched a rebellion intended to establish a regime of perfect communism, known as the Taiping, or “Great Peace.” Throughout its brief and bloody history, the movement maintained aspects of Christianity, and it always cherished that original Good Words to Admonish the Age, but it accepted the faith in a curious and deviant form. Recruits were required to learn the Lord’s Prayer within a set period, upon threat of death. The Taiping movement came close to overthrowing the Chinese empire, in what became by far the bloodiest conflict in human history up to that point. Tens of millions died.

Very fortunately, Edwin Stevens did not live to witness the consequences of his simple act of evangelism. Who knew that New Testament Christianity could potentially supply the ideology for radical resistance which, given the appropriate circumstances, could even become an empire slayer? But that message often took strange and unsettling forms. Unwittingly, empires and the missionaries they favored could spark strange and troubling movements. Sometimes these emerged on American soil, but they could surface in many distant and unpredictable corners of the world.