A staggering array of human hands across continents and generations created the tradition of sacred song in the American South. Songs and hymns featured in nineteenth-century revival and church services—some of which are still familiar—were made by ancient Hebrew poets, enslaved African Americans, Jacobean translators, medieval monks, eighteenth-century English Nonconformists, shape-note transcribers, preachers, laypeople, composers, and musicians in Africa, the Caribbean, Europe, and North America. These poems and tunes were memorized, recited, sung, hummed, and whistled by people—literate and illiterate alike—on byways, in barns, schoolrooms, fields, and around hearths in countless neighborhoods. They were printed in cities and small towns, on wooden and iron presses, using paper made by free and enslaved workers, in mills scattered along rivers and creeks. Then they were stitched together or bound into pamphlets and small books by tradesmen and women. These were hawked for pennies apiece by peddlers, preachers, printers, colporteurs, and storekeepers on behalf of denominations, publishers, and missionary and Bible societies.

This is just a partial recounting of how human voices and printed pages made a repertoire that was at the heart of daily life. The familiar part of this story concerns human memories and voices. Less familiar to us is the importance of printers, colporteurs, and readers to this tradition.

This is because southern culture has been understood primarily as an oral tradition. Accordingly, its tradition of sacred song has been studied by a small cadre of musicologists and folklorists, who document oral and folk traditions, rather than by historians whose natural domain is the handwritten and printed page. No doubt, oral tradition was—and remains—critical to the transmission and creation of sacred song. African American spirituals were sung into being by people who wove African traditions with images and language from the King James Bible, spread along roads, across fields and at revival meetings to black and white singers who learned them by heart.

But as I explain in A Literate South: Reading before Emancipation (New Haven, 2019), the prominence of oral tradition to popular understandings of southern culture, along with the mistaken view that print did not widely circulate in the region, has veiled the rich history of printed song in the region. No American, even those who could not read at all, could escape the influence and presence of print in the nineteenth century, much like how the technologically inept among us find our lives shaped by the internet. Tens of thousands—by some estimates hundreds of thousands—of cheap songsters, song sheets and pamphlets were printed and sold by tradesmen in the southern states, transmitting these songs not only around the region, but also across the Atlantic and from the southeastern coast to Philadelphia and other points north and west.

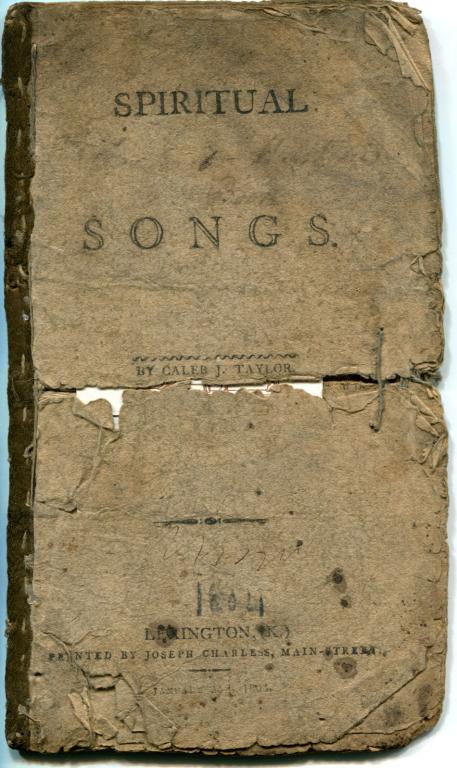

One of these forgotten objects graces the cover of my book—a pamphlet, or songster, printed in 1804, on behalf of Rev. Caleb Jarvis Taylor, a Methodist convert who preached across northeastern Kentucky. “Spiritual Songs” was printed in Lexington by Joseph Charless. The title has escaped notice even by hymnologists, but this fragile copy somehow survived through the generations, at one point literally ripped in half before being lovingly restitched, to be deposited in the public library in Cincinnati, Ohio. I suspect it is the only copy that survives because pamphlets like this were literally ephemeral. Scholars believe that most of the output of small printing offices like Charless’s has not survived.

Yet ephemera can have enormous influence in its short life span. In the South, it transmitted songs written decades or centuries earlier and an ocean away, many of which were loved and memorized to become part of the oral tradition. One of the most surprising legacies of print was its place in the making of African-American spirituals. The great Harvard musicologist Eileen Southern traced the influence of the first printed collection of African American hymns, Richard Allen’s A Collection of Spiritual Songs and Hymns, Selected from Various Authors (1801) to the first compilation of African American spirituals, Slave Songs of the United States (1867). These were collected on the South Carolina coast by northern troops and teachers during the Civil War, and for generations it was assumed that they originated there before Southern’s research ingeniously concluded that they were the product of independent black congregations in the Philadelphia area.

Allen was the first bishop of the African Methodist Episcopal Church, and his hymnbook spread along with his denomination. His Philadelphia congregation—Bethel Church, known as “Mother Bethel”—was the most important independent black congregation in the nation. The congregation’s singing of both Anglo-American hymns and spirituals was legendary. This was reflected in Allen’s book. About half of the hymns were from the Anglo-American tradition, while the rest were American spirituals. In the two decades after the hymnbook appeared, at least ten other popular compilations used by white and black singers included a large number of the texts originally chosen by Allen. There was a particularly close relationship between Allen’s book and “the Baltimore Collection,” an anonymous compilation that was the most popular songster of the period.

Allen’s hymnbook offers a fine example of how songs from the oral tradition found their way into print only to return to oral tradition. That is to say, favorite songs learned by ear were printed, only to be memorized in worship services and revival meetings by new singers, the literate and illiterate alike. This movement from page to memory offers early evidence of the broadly interracial sacred musical tradition that blossomed after the Civil War into genres ranging from white and black gospel to Civil Rights anthems to rock and roll, as documented by my colleague Paul Harvey.

The importance of printed sources to Southern sacred song has broad implications for how we understand our history. Most of the hymnbooks, shape-note tune books, and songbooks dear to southern singers featured works native to the region, but they were printed in Philadelphia, or New York, or Cincinnati before being boxed up and carried back south. Publishers, authors, and booksellers sought customers wherever they could be found, in free and slave states, upper South and upper Midwest. Books are technology, and by nature, supremely portable bearers of culture without regard for the political, geographical, and social boundaries to which humans so stubbornly cling. The story of sacred song in this single region of the early United States underscores how this genre unified American singers across racial, social, and geographical boundaries. It also shows that technology can enhance rather than undermine our society by spreading the marvelous things that human voices and pens have made.