If you study the historical background of the Old Testament, you will very soon come across the Sea Peoples. According to a widely told narrative, these were ferocious barbarian peoples who erupted into the civilized worlds of the Late Bronze Age Mediterranean around 1200 BC. They posed a deadly threat to Egypt and were likely responsible for destroying other great states of the day. Among their ranks were the Peleset, the Philistines, who settled in Palestine, and ultimately gave the land their name. They feature very extensively in the historical accounts of the early Hebrew states and kingdoms.

So much is widely accepted, but some recent scholarship is challenging that model: see especially a major article that appeared in the prestigious pages of the New Scientist, by Colin Barras, and titled “Who Were The Enigmatic Sea Peoples Blamed For The Bronze Age Collapse?” Now, we are told, “new evidence shows that many of our ideas about this turbulent time need completely rethinking.” Rethinking is always a useful exercise, but in this case, I think most of the proposed revisions are simply wrong, and I will demonstrate that by drawing on other analogies, both ancient and early medieval.

I make the obvious point that the whole category and terminology of “barbarians” is wildly subjective and unstable. Everybody is a “barbarian” to someone: just read what nineteenth century Chinese elites said about the obnoxious British and French arriving on their shores. How we apply the label is largely a matter of whose written records happened to survive for the uses of later historians. Having said that, bear with me as I will use the loaded B-word without elaboration in this short piece. On every occasion, just assume that quotes are implied.

The Sea Peoples

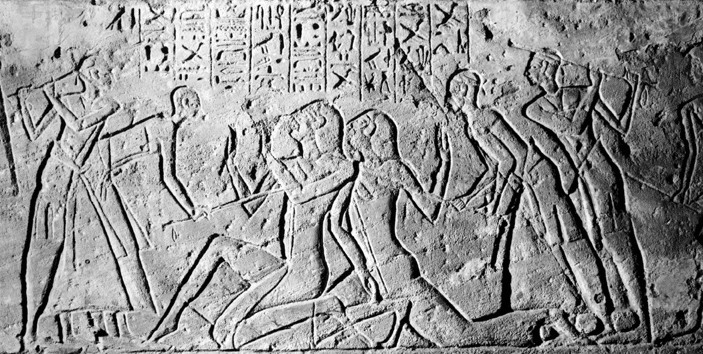

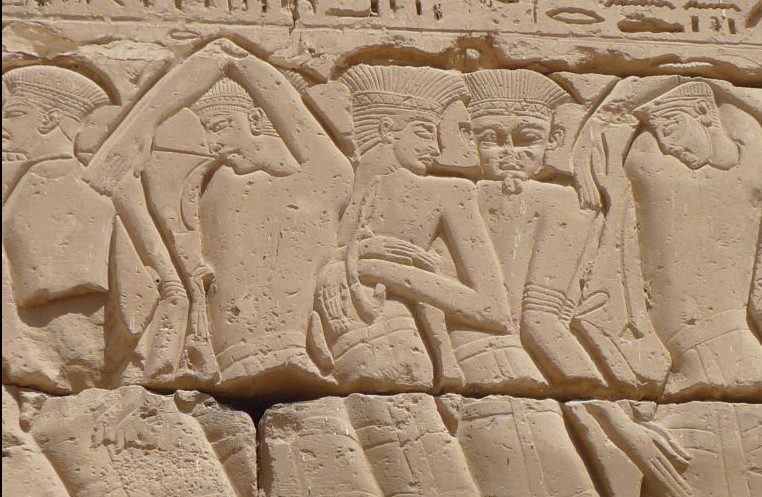

The Sea Peoples first appear in Egyptian inscriptions in which Pharaohs Rameses II and III tell of these fierce raiders who swept all before them, or at least until they met their own mighty armed forces. Rameses III was especially boastful. Some of those raiders, by the way, wore the kind of horned helmets we easily associate with barbarians and pirates.

The origins of these Ekwesh, these Peoples of the Countries of the Sea, are widely discussed. Among the recorded names that appear in ancient sources, we find such ethnic labels as Lukka, Shekelesh, and Sherden which might or might not correspond to such later terms as Sicilian and Sardinian, as well as Lycians and (probably) Greeks. I will over-simplify grossly here, but one standard theory suggests that various climatic stresses and disasters forced a mass movement of peoples from the Aegean and Anatolian worlds, and possibly from the Western Mediterranean. Rhodes is always an intriguing source for the raiders, as are Cyprus and Crete. These peoples formed a confederation which struck at Egypt and other temptingly wealthy lands.

What happened to them after that point is debated. If we accept the linkage with Sicilians and Sardinians, that might either mean that some of the raiders came from those western parts, or else that is where they ended up after some wanderings. We can be confident enough about the fate of the Philistines, and recent genetic investigations confirm that they had roots in Greece or southern Europe.

Much of our interpretation of this whole story was formulated in the nineteenth century by European historians who held views about ethnicity and migration that are now very much out of fashion. Even so, the broad outline remains, and this is what Barras is challenging, or rather, what is being criticized by the range of experts he is interviewing. As he says, the older picture of widespread cumulative calamities

sounds more like a Hollywood plot than an account of real history. [Some current scholars] argue that a more critical examination of the evidence suggests there was, in fact, no destructive wave of migrants sweeping across the Mediterranean and no centuries-long drought. In fact, some even doubt there was a Late Bronze Age collapse in the sense of a single region-wide disaster. “People turned this up to 11, and we have to take it back down to 3,” says Jesse Millek at Leiden University in the Netherlands.

These revisionists dislike the traditional picture in several ways. Just to take one instance, they note the appearance of new groups, but suggest that these might be operating on an invited and approved basis, rather than crashing into the old established order. The Sea Peoples who attacked Egypt might have been working for (or with?) the Hittites, rather than being freelance marauders.

Critics also note the very gradual nature of the incursions, and differ radically from the image of a sudden overnight appearance of countless thousands of burly warriors in their horned helmets. More generally, these critics challenge the idea of a near-overnight Bronze Age collapse that affected the whole region. Perhaps individual states failed separately and independently:

At first glance, that sounds implausible: so much chaos occurring simultaneously is surely no coincidence. But, in reality, the timeline of these events was probably more relaxed than that. “The destructions in Mycenaean Greece could have taken place over 15 or 20 years,” says Helène Whittaker at the University of Gothenburg, Sweden. Across the region more broadly, it might have occurred over 50 years, says Manning – hardly evidence of a single, acute crisis.

I will return to these comments about the “relaxed” chronology.

One oddity about Barras’s article is that it suggests that the Sea Peoples are commonly blamed for the Bronze Age collapse, which most surely attribute primarily to climate factors. Barbarians or climate? The article goes back and fore on these emphases.

In summary,

We still have plenty to learn about the dramatic events at the end of the Bronze Age. But as the evidence continues to accumulate, we may finally be able to acquit the Sea Peoples. It is possible they have been framed for “crimes” that may never have happened.

Vikings

As I read this critique, I felt a powerful sense of déjà vu as it so often recalled other periods of which I have some knowledge.

The chronological issue emerges strongly. If we look at the Viking raids that so devastated much of Europe in the early Middle Ages, they were far more gradual than our conventional accounts suggest. Anyone who knows anything about that story is familiar with the shock and astonishment that greeted the attack on the northern English island of Lindisfarne in 793, but this was in no sense the start of an overnight revolution. Raids were sporadic until then 840s, when the Vikings were sufficiently well established in many local bases to target virtually any destination they chose, including Paris and the Western Mediterranean. That crisis then endured for several decades more. In other words, the seemingly sudden and revolutionary shock of the Viking incursions actually developed over around half a century, very much what is suggested for the Sea Peoples, and the whole span of the crisis was over a century.

Did Europe in these long decades suffer a “single acute crisis” that came close to destroying its emerging Germanic/Latin civilization? Definitely. In historical terms, such an existential crisis can easily be spread over a half century or more.

The Viking situation also forces us to think what we mean when we hear of raiders or pirates. In the early days, the Vikings might hit with a couple of ships, on a very targeted operation against wealthy monasteries. When they found how easy matters were, and how weak the opposition, they moved up to ever larger ventures and groupings, until in 865 England was hit with a whole “Great Army.” Kings now took the lead, and they were looking for new realms to rule, not just plunder. I don’t know if that trajectory also occurred in the Sea People era, but we should always ask these questions about size, scale, organization, and intent. These things varied a lot at different stages over the long periods of crisis.

Incidentally, there is no doubt whatever that Europe’s ninth century crisis was intimately connected with climate disasters, which in the same years had a near-terminal effect on both the Byzantine Empire and the Caliphate. Particularly in the years around 810, both realms came very close to collapse.

Extraordinary climate crisis combined with horned helmeted barbarians – does that sound at all familiar from the Late Bronze Age Mediterranean? If the climate crisis had not been so appalling, maybe the early medieval states would have been stronger and better prepared to resist the Vikings, but they were not. In other words, the invaders were a symptom of catastrophe as much as its cause. That was true in the early ninth century AD. Might it have been true around 1200BC?

So does that ninth century AD story sound like a script for an overheated Hollywood epic? Maybe it does. Sorry about that, it’s just what happened. History is like that.

The Age of Alaric

But there is an even stronger analogy to the Late Bronze Age crisis.

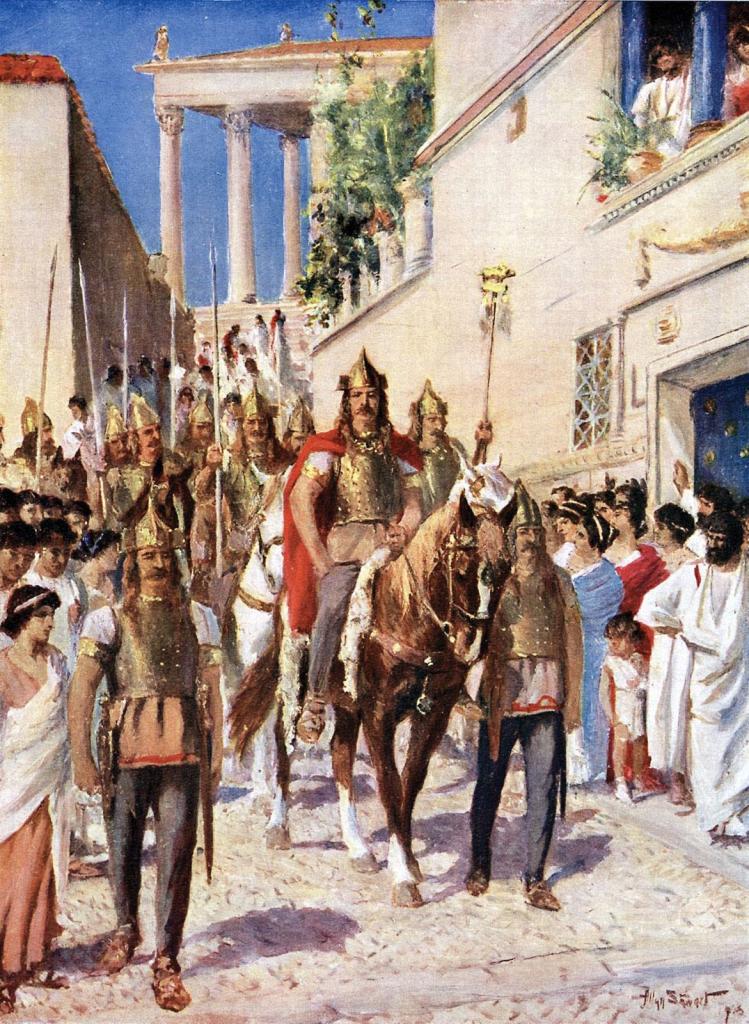

Again, as everyone knows, in the year 410 the Goths sacked Rome, causing a tectonic cultural shock that echoes through many Christian writings, including the work of St Augustine. In fact, reading those accounts, we might well imagine that the Goths had appeared almost overnight, which they certainly had not, and their onslaught was anything but new. Facing intolerable pressure from the Huns, the Goths had moved into Roman lands several decades earlier, and accepted Roman service. Atrocious treatment at the hands of the Romans caused a fatal split, and in 378, Gothic forces defeated the Romans at Adrianople, in one of the worst military catastrophes the empire ever suffered. The Emperor Valens was killed on the battlefield.

Thereafter, successor emperors tried many strategies to accommodate to overcome these increasingly terrifying frenemies, with many attempts to set up contracts or deals. To see how Gothic positions and attitudes fluctuated over time, check out the lengthy Wikipedia entry about their King Alaric, who eventually sacked Rome, very much against his wishes and better judgment. By the way, the Goths at this stage were Arian Christians, who were appalled when their orthodox Catholic Roman enemies violated an Easter truce.

Over the following decades, a variety of other peoples surged into imperial territories, often beginning as mercenaries or contract forces, and then, on occasion, moving into rebellion. One critical change happened in 405-407 when the Roman commander Stilicho – himself a barbarian – removed most forces from the western borders to defend Rome against Alaric. Several Danubian peoples took advantage of the new opportunity to cross into Roman Gaul. The customary listing of the peoples involved includes Vandals, Alans, and Suevi, but seriously, who knows what other peoples might have been involved? The situation in fact quite closely recalls the debates over the exact ethnic makeup of the Sea Peoples.

The accumulation of interlinked catastrophes between 405 and 410 proved fatal for the old imperial order. During the fifth century, various Germanic groups created whole new kingdoms on what had been Roman territory. The Vandals took Carthage in 439 and over the next century ruled a mighty kingdom in North Africa. The Visigoths ruled Spain until 711, and the Burgundians gave their name to a sizable area of what we would call southern France. Large sections of the former Britain became Anglo-Saxon England. The Ostrogoths took Italy. The Western empire staggered on for several decades, but it was wound up an independent entity in 476 (Of course, New Rome continued to flourish in the east).

Remember that recent critique of the Bronze Age crisis, which was allegedly no crisis because it was spread over some decades? If we look at the Roman world between say 378 and 415 or so – over almost forty years – then Hell, yes, there emphatically was “evidence of a single, acute crisis,” and one with prolonged consequences. Would Barras and his experts still be speaking of all this in terms of a “relaxed” chronology? The Western Roman empire in those years found precious little time for the luxury of relaxation.

Some Lessons

The details of these tribes and kingdoms do not matter, but for present purposes, several points stand out.

First, a really disastrous series of empire-slaying crises can be a very long drawn out process, and the fact that the main sacks and battles are spread over lengthy periods does not diminish that fact.

Second, it would quite normal for empires to try to defuse such threats by actually hiring the invaders, or trying to come to some kinds of terms with them. That is a standard part of imperial practice, If you can’t beat them, hire them. Arguing that Group X was working for Kingdom Y at any given point says nothing about their origins, intentions, or ultimate attitude towards that kingdom. We can usefully recall G. K. Chesterton’s framing of the four stages of empire: “Victory over barbarians. Employment of barbarians. Alliance with barbarians. Conquest by barbarians.”

Third, we don’t have to decide between blaming the fall of a state or state system on either climate or barbarian invaders. The climate disasters created the conditions for the barbarians. Maybe the barbarians just populated the landscape as it was falling into ruin through climatic factors.

I add one thing. Barras speaks of the prolonged drought that so weakened the late Bronze Age world, and critiques claims about its seriousness and length. That is fine. But there might well have been another and quite separate climatic cataclysm that destroyed that old world, such as a super-volcano. Disproving (or questioning) the drought theory does not eliminate climate as a decisive factor.

What Drives Barbarian Invasions?

Finally, the forces driving such barbarians might be very mixed indeed. The Romans saw their barbarians as greedy interlopers seeking to build their own empires, and some of course were. But most of the new arrivals were actually refugees fleeing from still nastier barbarians expanding into their space, and that especially meant the Huns.

Did some comparable spark began the Sea People explosion? As I read the New Scientist article, the author suggests that pressure from some northern invaders could have driven southern Italian peoples to seek new lands further afield, whether that meant in Greece, or further afield across the eastern Mediterranean. Conceivably, these new pressures could have shattered the Mycenaean world, and created an almighty knock-on effect. I wonder if the Sea Peoples were themselves refugees and, dare I say, asylum seekers?

The barbarians you see crossing your frontiers and landing on your shores might actually mark the last stage in a series of connected shocks that had their origins a thousand miles away, and which initially affected peoples very different from those who appear in the historical record. Think billiard balls.

Going back to the Gothic age, their motivation through much of this era was not seeking to grab new lands, but rather to seize food supplies, and official rations. The Vandals targeted Africa precisely because that was then so rich in food supplies, and it served as Rome’s granary. Was something similar driving the Sea Peoples? How would we know?

I am all in favor of asking challenging questions about conventional historical models, even if that sometimes looks like nitpicking. But in any such endeavor, we really have to think very carefully about possible historical analogies. In the case of the Sea Peoples and the Late Bronze Age crisis, the critics really need to get out more. It’s time for them to see other centuries.

Tell me again why we should not turn that Late Bronze Age crisis up to eleven? It destroyed a whole world.

See now the excellent book by Eric H. Cline, After 1177 B.C.: The Survival of Civilizations (Princeton University Press, 2024)