Today’s post is a little bit angry so be forewarned. I guess I have a new pet peeve. And frankly, it is not merely a pet peeve. It is a trespassing of the third commandment: that we not misuse the name of the Lord our God (or as we popularly refer to it, taking the name of the Lord in vain). This is often understood as meaning that we have to be careful not to use God’s name as an expletive but this isn’t the primary way in which we risk disobeying this commandment. Much more dangerous is the impulse to associate the profane with the holy: to deify our selfish pursuits and to use the name of God to justify our domination and exploitation of one another.

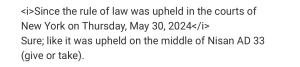

So when I saw comments like this one on another Anxious Bench post

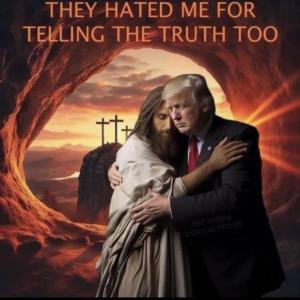

and Facebook memes like these:

I bristled viscerally. Not just because of the general cringe that many Facebook posts invoke but because there ought to be considerable care whenever someone claiming to be Christian invokes the name of Christ.

Also, white Jesus generally invokes that reaction for me anyways.

Incidental coincidence between particular circumstances in Jesus’ life and circumstances in one’s own do not justify comparison. But the issue is not primarily comparison. It is identity: the claim that this person is like Jesus or at worst, is a Christ figure. At that point, we move past pet peeves. We move into idolatry. I invoke that language intentionally, as it is the kind of language that communicates the gravitas of such an error. But it is a practice that we have grown accustomed to seeing in our history.

In 1865, following the Civil War, a New York based printing company released a print of Abraham Lincoln and George Washington with clasped hands in front of a pillar with “Liberty” in the stone and a constantly burning flame atop it. The subtitle was, “Washington and Lincoln: The Father and the Saviour of Our Country”. Those invocations were not accidental: after all, you’ve essentially covered two persons of the Trinity. But they do exemplify the ways in which civil religion can easily traffic in the language of Christianity. The titles of “Father” and “Saviour” have the rhetorical import that they do because, in our discourse, they are laden with the weight of biblical and theological history. To place that upon the shoulders of men (rather intentionally, men) like Washington and Lincoln, especially with their complicated histories, is not only unfair to them, but blasphemous to the Lord.

This was a significant element of Civil War rhetoric where both sides sought a Messiah to rally around, and it factored significantly into the formation and spread of the Lost Cause, where Southerners constructed narratives about their own history, in order to deal with the loss they suffered in the Civil War. Included in these narratives were assumptions of the inferiority of Africans and the necessity of their economic subjugation for the health of the nation. But paired with that was the deeper assumption that God was on their side, and it was that assumption that proved to be most resilient. When this became an assumption rather than an occasion for real self-reflection, self-justification reared its ugly head. That same risk applies to us today when we assume that “God is on our side.” That assumption is often but moments away from atrocity, if it is not invoked to justify them in the first place.

The other example that sticks in my mind is that of Newsweek’s January 18, 2013 edition, which featured a prominent picture of Barack Obama with the title, “The Second Coming: America Expects. Can He Deliver?” The author was tapping into a tendency that it seems many Americans have: link their political leaders to Jesus. And yet, any real comparisons are superficial at best, flatly contradictory at worst. Rarely are our political leaders poor ethnic minorities living under the boot of empire and spending their time living among, healing, and lifting up the poor while castigating the rich, while also happening to be the enfleshed Creator of the Universe. The Incarnation was a singular event. Let’s keep it that way.

All of this is symptomatic, however, of a larger political and theological tendency: the desire to see the conflation of the kingdoms of the world and the Kingdom of God. It is a tendency that goes back to the Edict of Thessalonica, the Theodosian affirmation of Nicene Christianity as the religion of the Roman Empire in 380. Constantine merely set the stage by formally giving Christianity legal status and by ushering in an age of toleration. The next step, however, was to turn toleration into dominance. In that move, what was only possible in the imaginations of Christians became a possible reality: maybe the kingdoms of the world could be the kingdom of God!

But we must remember this: the distinction between the Kingdom of God and the kingdoms of the world is not one that can be overcome by creativity. It is a distinction at the level of logic. The former operates by a deep logic of love. The latter necessarily operates by a logic of violence, retribution, domination, and often exploitation. Even in the Edict of Thessalonica itself, the establishment of state-sponsored orthodoxy meant that the state could also apportion for itself the power to repress heresy. The same power was extended to the state by the Westminster Confession, where we are told that the civil magistrate “hath authority, and it is his duty, to take order, that unity and peace be preserved in the Church, that the truth of God be kept pure and entire; that all blasphemies and heresies be suppressed; all corruptions and abuses in worship and discipline prevented or reformed; and all the ordinances of God duly settled, administered, and observed.” (WCF 23.3) That is a tremendous amount of power to hand over to an institution whose primary mode of coercion is the sword. I could talk about white Christian nationalism here too but others have done so more comprehensively than I will. The temptation is always before us to use the powers of the state “for the sake of the Kingdom of God” but those efforts are doomed both to fail and to kill.

Which brings us back to our current milieu. The willingness of anyone to associate their political cause with the divine cause is a terrifying prospect. If God is on your side, everything is permissible. White supremacists seem to be ever ready to invoke a rallying cry of the Crusades, “Deus vult”, in order to justify their own project. But that is just as blasphemous for them as it is whenever the name of God is mobilized for domination, exploitation, and murder. Our consciences must be resensitized to that fact.

So where should we go from here? Be skeptical whenever the name of Jesus shows up in public discourse. Ask the question: what does this person gain by invoking the name of God? Is good news proclaimed to the poor? Are the prisoners set free? Are the blind gaining sight? Are the oppressed set free? Does Jubilee follow from it? Or is it just the case that someone is able to further justify their own political position? One is the way of the Christ.

So no. Trump is not a Christ figure because he was found guilty in a trial. Much more is required for someone to resemble Christ. And if you’re not talking about Jesus and the people whom He has called to bear witness to the new community of justice, power, love and equity that He has formed in obedience to His Father and by the power of the Holy Spirit, respectfully…

Keep the Name out of your mouth.