Today I have the pleasure of welcoming a guest contribution from my Wheaton College colleague and friend, Nathan Luis Cartagena (Ph.D., Baylor University). Cartagena is an Assistant Professor of Philosophy, whose teaching and scholarship focus on Thomas Aquinas, James Baldwin, Critical Race Theory, Military Ethics, Evangélic@ Theology, and Christian Pedagogy.

Today I have the pleasure of welcoming a guest contribution from my Wheaton College colleague and friend, Nathan Luis Cartagena (Ph.D., Baylor University). Cartagena is an Assistant Professor of Philosophy, whose teaching and scholarship focus on Thomas Aquinas, James Baldwin, Critical Race Theory, Military Ethics, Evangélic@ Theology, and Christian Pedagogy.

During Holy Week of 2001, the British Broadcasting Corporation and the Discovery Channel coproduced the documentary Jesus: The Complete Story. The documentary chronicling Jesus’ life included a visual rendering of him. Using a two-thousand-year-old Jewish skull and skin and hair colors based on third-century frescoes of Jewish faces from the ruins at Dura-Europos in Syria, forensic artist Richard Neave created a computer-generated image of what Jesus might have looked like. The final image offered viewers an olive-skinned man with short dark curly hair and brown eyes. This image decidedly differed from traditional ones dating back to the fifth century, and more modern renderings of a white-skinned, blond-haired, blue-eyed Jesus. And many found Neave’s depiction repulsive.

Pulitzer Prize-winning columnist Kathleen Parker was one of the repulsed. In her article, “Makeover Gone Mad on Jesus,” Parker decries the fact that “this new Jesus looks like no one familiar. The willowy, long-haired figure who in picture books attracted children…now looks like the kind of guy who wouldn’t make it through airport security.” Parker deemed the new Jesus’ jaw and nose particularly disgusting. The jaw “looks likely to chomp down on a brontosaurus thigh, while the wide nose appears like “a snout that snorts.” Parker concludes by denouncing researchers who try to “debunk” White Jesus, arguing “that biblical revisionists won’t be satisfied until they discover Jesus was really a bisexual, cross-dressing, whale-saving, tobacco-hating, vegetarian African Queen who actually went to temple to lobby for women’s rights.” In today’s parlance, Parker decried the documentary and relevant researchers as WOKE.

Parker’s racist response is instructive for Christian pedagogues who work in historically and predominately White Christian colleges and universities. Many of our students find a non-White Jesus “wrong” or “disgusting” because technologies like picture books have trained them to see Jesus as White—and only White. Children’s bibles are replete with him. So are stained-glass windows and movies. These artifacts shape our students’ imaginaries. Our students accepted this totem as part of a wider religiopolitical, cultural unconscious during childhood. Now they expect portrayals of White Jesus as Jesus without realizing it. They see White Jesus as the visually unmarked, non-qualified Jesus. We Christian educators committed to liberatory, healing pedagogies must help our students see differently.

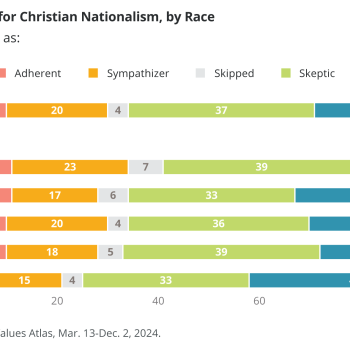

But how to do that when, as Parker’s response shows, naming and unmasking racist totems often evokes hostility? We want our students to see anew, not retreat and retrench into prepackaged discourses and talking points pervaded with racist domination. How to create space for repulsion and critical reflection? How to walk with the unknowingly wounded? How to walk the narrow road amid the surges in White Christian Nationalism and White Christofacism since Parker’s piece?

I raise these questions as a Puerto Rican philosophy professor teaching courses on racism and white supremacy at Wheaton College. One of my answers reflects this vocation’s particularities but may carry cross-disciplinary and institutional insight.

Most of my students unconsciously assume that, if someone from the eighteenth or nineteenth-century opposed slavery, they also opposed white supremacy. We name and interrogate this false assumption through a close reading of passages by the nineteenth-century Scottish historian and philosopher David Hume. Hume vehemently opposed slavery. His essay “Of the Populousness of Ancient Nations” (1752) makes this clear. But despite opposing slavery, Hume embraced and championed white supremacy. To see this truth, my students and I analyze an infamous passage from the revised version of his essay “Of National Characters” (1753). Hume writes:

I am apt to suspect the Negroes and in general all other species of men (for there are four or five different kinds) to be naturally inferior to the whites. There never was a civilized nation of any other complexion than white, nor even any individual eminent either in action or speculation. No ingenious manufacturers amongst them, no arts, no sciences. On the other hand, the most rude and barbarous of the whites, such as the ancient GERMANS, the present TARTARS, have still something eminent about them, in their valour, form of government, or some other particular. Such a uniform and constant difference could not happen, in so many countries and ages, if nature had not made an original distinction betwixt these breeds of men. Not to mention our colonies, there are NEGROE slaves dispersed all over EUROPE, of which none ever discovered any symptoms of ingenuity; tho’ low people, without education, will start up amongst us, and distinguish themselves in every profession. In JAMAICA, indeed, they talk of one negroe as a man of parts and learning; but ’tis likely he is admired for very slender accomplishments, like a parrot, who speaks a few words plainly.

Students and I read this text at the end of a class. Then we reread it at the start of the next one, giving special attention to the initial two sentences: “I am apt to suspect the Negroes and in general all other species of men (for there are four or five different kinds) to be naturally inferior to the whites. There never was a civilized nation of any other complexion than white, nor even any individual eminent either in action or speculation.” Having had my students hear and read the two time and over the span of two classes, I ask them to list “advanced” non-White civilizations and “eminent” non-White individuals that Hume would’ve known about and that falsify his second sentence. Students rapidly cite civilizations like the Aztecs, Mayans, and Ottomans, but they struggle to recall any “eminent” non-White people. More important for this essay: Only four students have mentioned Jesus. I share this fact with the class. Then I ask them to consider what contributes to this lopsided outcome.

As students consider potential causes, I show them a Google search for “Images of Jesus.” Visuals of White Jesus abound. To emphasize their prevalence, I scroll down the search-results page for thirty seconds. Down, down, down we go; and up, up, up appear White Jesus. Line after line is roughly the same. In less than a minute, students begin to get the point: They aren’t primed to think of Jesus as a refutation to David Hume because they’re primed to think of Jesus as White. And because they conceive him as White, he doesn’t hurry to their minds as a counterexample.

Then comes a challenging moment for many. I show them a Google search for “Historically Accurate Jesus.” We focus our attention on two particular images, Richard Neave’s depiction, and a more recent depiction by Dutch AI artist Bas Uterwijk. Some students audibly gasp when they see these images. Others experience a shocked silence. Still others begin to cry. We don’t rush their initial experiences. We take time individually and in groups to process what we seen and how it relates to David Hume. Then we share comments and questions.

An assumption that routinely surfaces in these conversations is that everyone depicts Jesus to look like them. Accompanying this assumption is another, and it’s deterministic: People always and only depict images of Jesus that look like them because its part of human nature to portray God in our image. I initially responded to these assumptions with anecdotal evidence like the doll test used in Brown v. Board. I reminded students that non-White children regularly draw and recognize White Jesus as Jesus. Sometimes students corroborated these points by recounting painful stories about watching non-White children chastising each other if they tried to color an outline of Jesus with anything but White. Racial surveillance begins early on and is not confined to White communities.

Though helpful, I wanted to give my students more than anecdotes. One of my colleagues suggested that I consider Julian of Norwich’s fourteenth-century verbal description of Jesus. I did. And now I use two excerpts from her book Revelations of Divine Love (“The Long Text 51”). Here is how the light-skinned English mystic describes Jesus:

The place where our Lord sat was humble, on the barren earth, deserted, alone in a wilderness. His clothing was full and ample as befits a lord; the cloth was as blue as azure, most sober and comely [i.e., beautiful]. His expression was merciful, the colour of his face a comely brown with pronounced features; his eyes were black, most comely and handsome, appearing full of tender pity; and within him there was a great refuge, long and wide and all full of endless heavens….

The blue of his clothing signifies his steadfastness. The brown of his fair face and the handsome blackness of the eyes was most suited to showing his holy gravity.

These passages stun students. Indeed, most have never heard nor read anyone portraying and praising the fittingness of Jesus having brown skin and black eyes. They hadn’t associated these traits with “holy gravity.” And they hadn’t imagined that that a fourteenth-century light-skinned English Christian would.

I grant that the pedagogical moves I’ve detailed won’t stem the tide of White Christian Nationalism nor White Christofacism. I also grant that these moves won’t work in most courses. I share them with the hope that they spark other ideas among Christian educators to help our students see White Jesus and how they’ve internalized him.