I have a long-standing admiration for the very influential scholar Ronald L. Inglehart. A couple of years ago, I posted at this site about Inglehart’s book on Religion’s Sudden Decline. My blog raved about the book, and Inglehart’s editor said he would pass it along to the great man himself, who would be pleased – not realizing that sadly, Inglehart had died just the previous day. That story has nothing directly to do with a recent media piece about Inglehart’s life work, which should be required reading for anyone interested in religion generally, or Christianity specifically, and certainly if they are using a global perspective. It provides a critical vocabulary for any such discussions.

The lengthy story in question appeared in the Economist under the title “Western values are steadily diverging from the rest of the world’s: People’s principles were expected to align as countries got richer. What happened?” Because that magazine enforces a tough pay wall, I will summarize the piece here, and I will sketch Inglehart’s underlying theory. I will also suggest some challenges to those ideas, drawing on a case-study that is counter-intuitive, and quite surprising.

Security, Trust, and Values

In the early 1980s, Inglehart was fascinated by the prospect of many millions of people moving from the old world of peasant societies to some kind of modernity, and asked how their values would change in the process. This became the foundation of the much-cited World Values Survey, WVS.

Central to his thought was the theme of security. As the Economist article notes, “the key to his work was to understand that a sense of threat drives people to seek refuge in family, racial or national groups, while at the same time tradition and organized religion offer them solace.” People adhered closely to those older groups and their collective values, while treating other groups – and the larger society – with suspicion and hostility. That was the idea expressed in somewhat more benevolent form by Margaret Thatcher in 1987, when she declared that

There’s no such thing as society. There are individual men and women and there are families. And no government can do anything except through people, and people must look after themselves first. It is our duty to look after ourselves and then, also, to look after our neighbors.

Members of Traditional/Survival worlds would agree heartily with that statement, except for the final clause about looking after neighbors. Such societies often look kindly on authoritarian political structures.

Towards Security and Modernity

Over time, security grows. National incomes grow, governments expand their involvement in health and welfare. Society becomes more stable, food supplies more reliable, lives more predictable. People live (much) longer, and infant mortality rates plunge. Growing out of this new security, the new world’s values tend to be secular, individualistic and rational. You can largely trust “others” and need not necessarily dislike or fear foreigners.

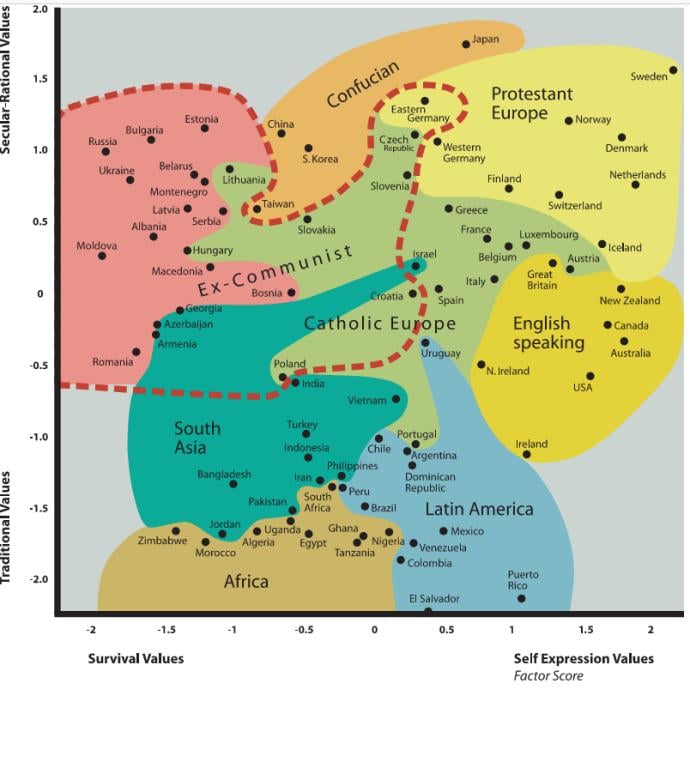

The WVS Cultural Map commonly used to track these changes has two axes, respectively Traditional /Secular, and Survival/Self-Expression:

*Traditional values emphasize the importance of religion, parent-child ties, deference to authority and traditional family values. People who embrace these values also reject divorce, abortion, euthanasia and suicide. These societies have high levels of national pride and a nationalistic outlook.

*Secular-rational values have the opposite preferences to the traditional values. These societies place less emphasis on religion, traditional family values and authority. Divorce, abortion, euthanasia and suicide are seen as relatively acceptable. (Suicide is not necessarily more common.)

*Survival values place emphasis on economic and physical security. It is linked with a relatively ethnocentric outlook and low levels of trust and tolerance.

*Self-expression values give high priority to environmental protection, growing tolerance of foreigners, gays and lesbians and gender equality, and rising demands for participation in decision-making in economic and political life.

Sweden, to take an obvious example, ranks extremely high in the Secular/Self Expression quadrant. Most African countries tend to be in the opposite Traditional/Survival zone: think Egypt or Nigeria.

I offer here a 2004 version of the famous Inglehart–Welzel Cultural Map of the World, which illustrates that WVS evidence, stressing that much has changed since!

The equivalent 2023 map can be found here – I will not reproduce it, for copyright reasons, but you can find it easily enough.

Over time, countries tend to move towards that upper right quadrant, of Secular/Self-Expression, and the ones already located there, eg Britain, move ever more steadily in that direction over time. Other English-speaking countries have likewise moved decisively towards those Scandinavian exemplars of “Protestant Europe.” In the most recent iteration, the United States has finally made that transition, from its rather anomalous position as a more Traditional/religious society, as it has moved much closer to the values of secular Europe. In this view, “Western values” – secular and individualistic – do not represent some kind of universal Great Truth, but rather are what naturally develops from these larger social and economic processes.

As I argued in my 2020 book Fertility and Faith, total fertility rates (TFR) offer a superb gauge of these changes, and do a fine job of predicting shifts in religious belief and practice, whether measured by nation or region. To maintain its population, a society needs a TFR of 2.1, and anything below that constitutes low fertility. Sweden’s rate cratered at 1.50 in 1999, and rose only to 1.66 by 2020. Not surprisingly, US fertility rates have suddenly started looking very Scandinavian indeed. And as I posted at this site a while back, we witness a steep “decline of death,” as death becomes something that is an ever less familiar part of daily existence. That change is a crucial component of modernity, and just think through the religious consequences.

Presumably, then, if we take a long enough perspective, all countries will eventually end up in that upper-right section. And indeed, the proportion of the world’s people living in extreme poverty has collapsed over the past forty years, due in no small part to qualitative improvements in China. But the point of the Economist story is that the move in values has been slower and patchier than the model predicts, as many countries that were Traditional/Survival have doubled down on that, including states like China that try to enforce those traditional outlooks with fearsome modern technology. Some countries, such as Venezuela, have retreated towards the Survival. Russia has moved towards the religious, as well as the Traditional/Survival. “Obstacles and detours” are much in evidence.

Security, Faith, and Secularization

Let me focus here on the implications for religion, which are actually not as explicit in Inglehart’s theory as we might like. The theory certainly used religion as a gauge, but look at those axes, so that Traditional and Secular counterpose each other. Obviously, the two words are not exactly opposites. A society can be very traditional without necessarily being religious. The Inglehart-Welzel list of criteria for defining these various categories (see above) is distinctly European and post-Christian, in ways that often do not mesh well with other faith traditions. It is also very much of its time. These are not fundamental value questions valid in all times and places, but rather the issues and concerns that happened to be agitating Euro-Americans in the late twentieth century.

Often too, the difference between “old” and “new” model societies involves the basic definition of what religion is. In a more Secular/Self-Expression society, religion is something you do, what you believe. In a Traditional/Survival society, it is what you are, almost a tribal identity. That is nothing to do with any inherent characteristics of the religion itself, it is just how it operates in a society marked by particular values.

Generally, though, the model does offer a good gauge of secularization, and especially if you trace how countries move during those intervening five year periods between waves. You clearly see this movement in Europe and Latin America, and the convergence of Protestant and Catholic Europe – or at least, the regions that could once be plausibly labeled with those religious terms. Over time, the grand shift of the model – crudely, let’s call it modernization or development – ensures that older religious systems give way to very different structures. Religious societies become secular, whether we measure that by statistics for belief or practice.

Much of the change reflects new roles for women, who find employment and experience education. Those changes in turn bring them into the work force, where they find a particular kind of existential security, and where life away from husband, family or clan becomes a possible option. Smaller families are far less involved in religious affairs. As I would argue, fertility and faith decline together, usually so rapidly that it is very hard to determine which factor hits first, and affects the other.

Like I say, this is a very rich set of theories, but the absolute foundation is that of security, and just as much, the feeling of being secure. Closely related to that is the sense of trust, or rather of trust in this world and its people. Look at trust, look at security, and you have a great foundation for trying to understand the social structures of religion.

So should we start drafting obituaries for religious faith? A couple of caveats are needed. I have already mentioned the first, which is that the latest WVS data seem to show real backtracking in this long term process. That might be a blip, or not.

Also, “religion” is not a simple one size fits all category, something that is either there or not. There are different kinds of religion, or different kinds of system that can be classified as religious, depending on local approaches. Religions are dynamic, and they adapt – commonly, while firmly denying that they are doing any such thing, and asserting that they are just doing what they have done since time immemorial.

Sweden. Sweden??

Finally, might the move to that individualist/secular Utopia be a self-limiting cycle? Look at Sweden, which I have cited earlier as the textbook model for secularization, for individualism and for values based on self-expression. As an unavoidable part of that package, Sweden’s fertility rate fell to unsustainably low levels, which in turn meant bringing in lots of immigrants to keep the society functioning. Most of those migrants came from societies that were distinctly non-secular. Twenty percent of Sweden’s population is now foreign born, and the Muslim share of overall population is at least eight percent. (By way of comparison, the current US proportion of foreign-born is below fourteen percent, but the non-Christian share is much smaller). A secular liberal society thus creates the inevitable conditions for the increasing role of non-secular and (often) non-liberal populations.

Conversely, the old stock society reacts to that change by reverting to non-liberal and quite Traditional/Survival policies. The most significant development in that country in recent years has been the dramatic rise of the Sweden Democrats, a party with fascist antecedents, although it has since cleaned up its act quite considerably, purging most of the blatant Nazis and skinheads. Even so, SD has parlayed its anti-immigrant and anti-multicultural credentials into an impressive 21 percent of the national vote, making it the country’s second largest party. SD provides essential outside support to the Swedish ruling coalition created last year, an alliance of three other firmly Rightist parties.

The Sweden Democrats used to be more explicit about their roots, using pictures of burly Viking warriors with shields inscribed “Keep Sweden Swedish!” (You can trace their evolving symbols and iconography here). Or to return to the phrase I quoted earlier, “a sense of threat drives people to seek refuge in family, racial or national groups.” Hold on, wasn’t that meant to be something we found in those old style poor Traditional/Survival societies, and not the modernized secular individualistic ones? Not in places like, well, Sweden? Now, the SD are absolutely not a religious party in any sense, and they represent no kind of Christian revival. But they certainly do manifest an unabashed revival of ethnocentric Traditional/Survival values of a kind that are surprising for prosperous Europe.

In passing, I am always amused to hear Americans hymn the praises of “Scandinavian social democracy,” which indicate that they (the hymners) have managed to miss the last couple of decades of that region’s history.

To take a related example, Germany is another very prosperous and developed country that stands high in the Secular/Self-Expression quadrant. Exactly like Sweden, it is also a land of historically low fertility and high immigration, which has opened the door to a far Right populist party very much like the Sweden Democrats, in the form of the AfD, Alternative für Deutschland. AfD is in the news currently as it is running at an alarming 21 percent in the polls, which is coincidentally the share of the vote that SD picked up last year in their country. A panicked German government is seriously considering banning AfD. Yes, obviously, Germans don’t want any kind of Nazi revival, but more immediately, they don’t want their party system to end up like Sweden’s.

In such instances, modernization and development demand massive social changes, which undermine people’s sense of trust and security, which in turn makes them rethink the values that led to that modernization and development in the first place. Threats and insecurity take many forms.

So maybe the processes are not as linear as we might initially think, still less inevitable.