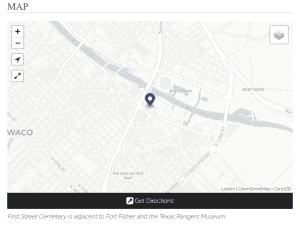

Perspiration, gathering into rivulets, slid into the folds of my clothing as I gazed at a faded headstone beneath the mottled shade of an aging tree. The incessant chirping of cicadas and the drone of passing cars on the I-35 freeway reverberated loudly against the silence of the stones. It was a blistering July afternoon in the middle of a Texas heat wave when I found myself at the First Street Cemetery in Waco, the city’s oldest place of internment, dating to 1852.

Two hours earlier, at the apex of the day’s heat, I had crossed over from Baylor’s campus – where I was in the final days of a wonderful two-week NEH Summer Institute, “Disputatio and the Pursuit of Wisdom” – to explore the Mayborn Museum and the Texas Ranger (law enforcement agency) Museum. When the latter closed at 5pm, I staggered out into the still-oppressive heat, drawn to campus and the coolness of my dormitory, but pausing first to investigate a plaque in the grassy stretch before me.

Image taken from a 2021 blog post by Morgan Ballard, The History and Tragedy of First Street Cemetery, which reads in part: “… the resting place for members of Waco’s early and diverse community. Burials include Veterans, Masons, Oddfellows, Woodmen of the World, Knights and Daughters of Tabor, and Court of Calanthe…”

My interest piqued at the idea of walking among the remains of Waco’s earliest citizens and learning its history from its dead, I stayed to explore. My phone had died half an hour earlier while taking photos of a Bonnie and Clyde exhibit at the Texas Ranger Museum, so I have no images of my cemetery stroll. I only have my musings about death and how we remember those in the past, those whose voices have been lost to us, those who cannot tell us their stories, and those who devoted their lives for morally objectionable causes.

As I maneuvered my salmon-colored sneakers carefully through the disorganized collection of markers, some modest, some ornate, and some bordering on the gaudy, I thought about the Early Modern Church’s admonition to the historical figures I study in sixteenth-century Spain and New Spain to contemplate their death often in order to die properly prepared. I described this phenomenon in a previous post: Death, Judgment, Heaven, and Franciscan Habits: The Art of Dying in Late Sixteenth-Century Spanish-Indigenous Cholula. And yet, as I picked my way through the grass collecting burrs on my shoes and birth and death dates in my mind, I wondered – how many of these souls had time to properly prepare? What of the mother who lost her 4-month-old child, interred in a tiny grave beside her? Was she prepared to accept the cross the Lord placed on her? Would losing her child help her to prepare for her own death, prompting her to live a good life in order to see her baby in the next life? This is a thought that consoled me when I was inconsolable following the death of baby #4 in utero a few years back; this thought still consoles me when a wave of grief overwhelms me unexpectedly, an experience I know I share with this young mother.

What of the multiple siblings buried side by side, children who died within days of each other – had they the time to prepare, to understand, or was their death sudden due to illness or injury? What of the parents who died within months of each other, prompted perhaps by an epidemic, illness, injury, or grief, surrounded by the graves of their children whom they orphaned at a young age? Or the mother who emigrated from England with her daughters, only to die after arriving in Waco, leaving her daughters alone in their adopted country, these same daughters buried beside her many decades later?

Map from Wacohistory.org

As I picked my way between pockets of shade, my clothing becoming more and more saturated from perspiration, I searched for the oldest person laid to rest in the cemetery; for about 45 minutes, it was a gentleman near the entrance born in 1805. Deep into my walk, however, I discovered a patriarch born in 1790 who was surrounded by at least 19 family members, based on the double last names of the women, though perhaps more of his family rested nearby. Who was this multi-generational family and what had their life in Waco been like? The collection of headstones, markers, and small mausolea, which were clustered together in two groups beneath a copse of trees, included at least one CSA marker – Confederate States of America.

Perhaps the most interesting stories in the cemetery – because they were unexpected – were the number of graves marked CSA. Despite the handful of Civil War skirmishes in Texas, I was startled to encounter the remains of so many Confederate soldiers in Waco; I wish I had taken notes, but if memory serves, some died during the war but not all, meaning some corpses would have been shipped home. The Confederacy and the Civil War had been much on my mind, since for the past few months I had been listening to the Gone with the Wind audiobook – 49+ hours – as I recovered from my major surgery in April.

Title page for Gone with the Wind on Hoopla

By the time I arrived at Baylor for the NEH Seminar, I had reached the chapters discussing the Reconstruction period after the war. Though sections of the book are difficult given the treatment of slaves by both Northerns in the south and by Southerners during and after the war, as a historian I was intrigued by the novel’s depiction of historical events. Listening to the book forced me to look beyond the moral reprehensibility of slavery and consider the deeply personal ways that the war affected Southern society, to consider the humanity of former slaveowners, to remember that they are body and soul, as are we all.

Earlier that day, Dr. Angel Parham, a sociologist from UVA and co-director of the NEH Summer Institute (alongside Baylor’s Dr. Todd Buras from Philosophy and the Honor College’s Dr. Phillip Donnelly) had led two workshops on MLK’s “Letter from a Birmingham Jail,” the “Statement by Alabama clergy” to which he was responding, and Malcom X’s “Message to Grassroots.” For nearly two weeks we had been applying the disputatio, that is, the structure Thomas Aquinas uses in the Summa Theologiae, to various texts to craft – and answer – wisdom questions, the goal being to become better teachers of these materials. That morning, based on the assigned readings, we asked broadly whether civil disobedience is ever justified, and specifically whether MLK’s defense of civil liberty was justified, breaking into groups to pull answers from the texts to help students see the logic behind the arguments. Dr. Parham began by providing us with historical background on first MLK and then Malcom X, tracing their personal experiences and intellectual influences (much as she had done the previous day with Booker T. Washington and W.E.B. DuBois). The socio-historical context of the writer is an important part of understanding the argument, she told us. The historian in me thrilled at the conversation.

Image taken from a 2021 blog post by Morgan Ballard, The History and Tragedy of First Street Cemetery, of the gravestone of Mary Rebecca Majors, dated 1858.

Walking through the overgrown burr-filled grass studying the gravestones, many tumbled and faded with time, rain, and wind, alongside others that had clearly been recently refurbished, the morning’s sessions ran through my mind for two reasons. First, because I wondered about the socio-historical context of those who rested beneath me and the stories they could tell; and second, because we had just been discussing civil disobedience in response to the legacy of slavery in this country, and here I was, walking with Confederates.

As I finalized this post and typed out the opening words of the First Street Cemetery plaque above, I looked up the groups mentioned and was startled to discover that the International Order of Twelve Knights and Daughters of Tabor is an African American fraternal organization founded in 1846 as the International Order of Twelve – an anti-slavery society. Similarly, the Grand Court Order of Calanthe – of which there is a Texas branch – is one of the oldest, largest, and most successful fraternal benefit societies for, and overseen by, African American women, dating to 1883.

As Christians, we believe that our souls live on after death, and that our earthly journey is only part of the story. But what a clash of journeys these individuals had! What would Civil War veterans say to us about their decision to fight for the Confederate States of America? About being buried alongside Knights and Daughters of Tabor and members of the Court of Calanthe? Would we listen? Similarly, what would the Knights and Daughters of Tabor and members of the Court of Calanthe say about living in Waco alongside veterans from the Civil War? About being buried alongside Confederate soldiers? Was there a history of violence between these individuals? I do not know enough about Waco history to answer that.

To see members of these and other groups resting side by side speaks to the diversity mentioned in the cemetery plaque, but more importantly, to the fact that in the end, we are all human, and we all die. Perhaps the Early Modern clerics were right – contemplating our death often will prompt us to live a better life. With death all around them, perhaps some of the 19th century buried dead at the First Street Cemetery in Waco did contemplate their death, did properly prepare, and did live better lives.