Today we welcome Holly Berkley Fletcher to the Anxious Bench. Dr. Fletcher is an American historian and the author of Gender and the American Temperance Movement of the Nineteenth Century (Routledge, 2008). For the past twenty years, she has worked for the US government on Africa issues and in her spare time writes on faith, missions, and cross-cultural identity. She is writing a forthcoming book on the missionary kid experience, which will be published with Broadleaf. You can find her on Substack or at azebrawithoutstripes.com.

Today we welcome Holly Berkley Fletcher to the Anxious Bench. Dr. Fletcher is an American historian and the author of Gender and the American Temperance Movement of the Nineteenth Century (Routledge, 2008). For the past twenty years, she has worked for the US government on Africa issues and in her spare time writes on faith, missions, and cross-cultural identity. She is writing a forthcoming book on the missionary kid experience, which will be published with Broadleaf. You can find her on Substack or at azebrawithoutstripes.com.

A long time ago, when I was still a history professor, I often started the semester by asking students to imagine they had no memory. How would they form an identity? What would be the basis for their actions, decisions, and relationships? And what about in the collective, how do a people know who they are and how to relate to one another, and what chaos and confusion might that society experience, without a memory, without history?

As a white American, who grew up in Kenya as the child of missionaries, these questions have added personal resonance. My identity and sense of belonging have always floated on a breeze. My memories became hazy almost immediately from the near-total loss of the familiar. I’ve never fully belonged there or here. I used to claim I was from Kenya, but with age and maturity, I’ve come to realize all the ways, mostly stemming from racial and socioeconomic privilege, that was never true. I’m from a bubble that burst long ago. I’m from a moment in time. There’s been a lot of grief in that. There’s been a lot of alienation. What I’ve grasped for is what we all want, to be noticed and welcomed for who we really are, beyond appearances or categories or stereotypes or whether or not we conform to a dominant culture.

Given how elusive that goal felt to me as a young person, it’s perhaps no wonder that I was attracted to the study of history. American history at least gave me a collective memory with which to work, as I wove a new identity to take into the rest of my adult, American life. (It helped that I had an engaging, encouraging history professor who saw my potential. And who turned out to be a Holocaust denier, but we won’t talk about that.)

Until graduate school, the version of history I had gotten, in evangelical institutions and cultures (even in Africa!), was as superficial and biased, as so much of my sense of belonging had been; it was a story that centered around the heroism of white, Christian men. (Did I mention my professor was a Holocaust denier?) The agenda was usually subtle. Instead of an explicit defense of slavery, for example, I heard things like, “at least the slaves became Christians,” “slaves were like members of the family,” and “true Christian masters were kind.” As a white evangelical, this narrative appealed to me on some level; I liked being one of the “good guys.” Growing up in Kenya, that’s how I saw my kind. My parents were greeted as spiritual rock stars everywhere we went, both there and here. And America manifested, as bags of food aid, arriving during famine, and diplomatic pressure on President Moi to democratize his people. America was all the sugary treats we inhaled on trips back to the US and stores filled with shiny new things and upside-down roller coasters that left you breathless. But that wasn’t the whole story. And just as no one seemed to know me, I didn’t really know America, either.

I remember the first time I was truly shocked by the truth. It wasn’t the two Black bodies hanging in a tree in the background, as grotesque and disturbing as that was.

It was a white girl standing in front of them. It was her face. She was half smiling, almost smirking, definitely excited. She was young, younger than me at the time, maybe 15. And she was surrounded by equally enthralled adults. It was a large crowd in Marion, Indiana in 1930, with not a shred of shame in sight.

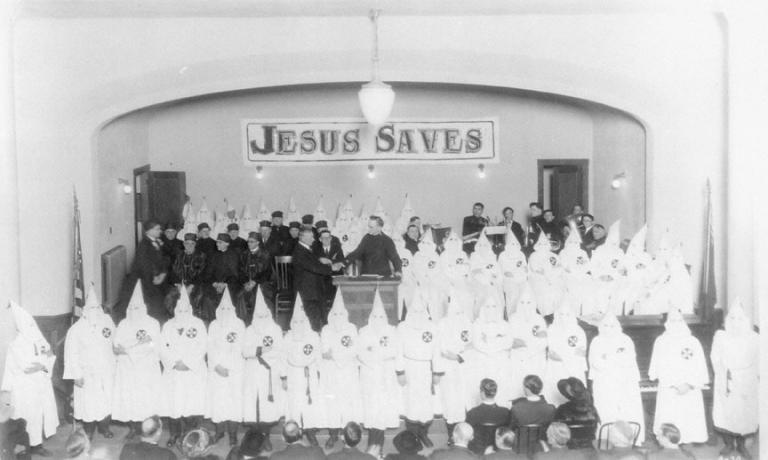

And I knew, from the time and place of the photo, that on Sunday mornings, almost all of those people would have had their hindquarters in a church pew. The girl probably sat there bored, doodling in the margins of her Bible, the way I did during church. Many of the men would have been deacons and pastors, like the ones I had been raised to admire and obey. There were other pictures of those same kind of people in full Klan regalia at the front of white churches.

And I thought I would be sick.

And I knew then that there was more to the story.

At first, it broke my heart. But then I realized that if there was more to that story–if there were things hidden from view and people hushed and lies told–then there was more to every story. It meant that there were more stories to be told. Stories deemed inconvenient and too morally complex by those who controlled the narrative. Stories that offered more opportunity for and variety of connection and recognition and empathy. Compelling stories. Human stories. The best kind of stories.

The work of history always involves choices and always presents an incomplete and biased picture, if only because it is constrained by the availability of sources. (I’m fond of saying that history is not only written by victors, it is written by the random, ordinary people who wrote a lot of letters to friends and family with hoarding tendencies.) History imposes an orderly narrative on the inherent chaos of events and the overwhelming multiplicity of human experience and perspective. But when those decisions aren’t guided by a pursuit of truth or an attempt at understanding, but, rather, those decisions are rooted in an agenda of fear and self-preservation, history loses its communal power. It becomes a weapon of war.

As a student of history, I have discovered that the white evangelical version of it is like many stories that culture tells. Selective, exclusive, carefully curated. A little too pretty, too sweet, simple-carbohydrate-teeth-rotting empty calories. For a religion supposedly based on the humbling, equalizing, but ultimately liberating fact that we’re all sinners—a great deal of effort goes into hiding the sins of the saints and insisting we all be one of them. And as the child of those celebrated as saints, I knew the pain of that all too well. I internalized my parents’ moral unassailability, and my heart filled with the septic sludge of self-loathing. I’ve heard something similar from the many other missionary kids I’ve known and formally interviewed. They’ve too often buried their stories in service to a fairy tale.

In the final analysis, it’s been a relief for me to hear, through my study of history, that America isn’t perfect. To find that white evangelicals aren’t super heroes. To realize how spacious the landscape of both Americanism and Christianity actually is. To see that belonging is found not in carrying forth a myth, but through the courage to tell the truth, of each other and, most importantly, ourselves. The truth will set us free.

Looking at America today, there seems to be a refusal by many to even try to tell it. Far from an authentic community, we are warring tribes desperately seeking control. Not surprisingly, history has once again become a major battle ground in that struggle. Victors don’t merely write history by winning past wars (or hoarding the most documents), they win by seizing the pen here and now. And when power is the goal, we completely lose the plot, the grand narrative of one, big, messy human family, in which all of us have a place, a contribution, and a responsibility to clean up after ourselves and leave the place nicer than we found it. All of us are invited to belong via the circuitous, vulnerable, humbling path of finding ourselves in that narrative.

Would that we could. It might begin to cure the deep loneliness, division, and despair that pervades our society. History isn’t a panacea. But it’s a place to start.