*Author’s note: A previous version of this post mistakenly identified Basil the Elder as the father of Gregory of Nazianzus. Basil was the father of Gregory of Nyssa. The post has been updated to reflect the change. My thanks to a close reader of the Anxious Bench for identifying the error. – JR*

Pope Callistus was a controversial figure in his day. Bishop of Rome from 218 to 222 AD, Callistus rose through the ministerial ranks quickly despite a checkered past and more than one run-in with the authorities. When in office, his policies proved, shall we say, unpopular with the hardline church leaders of his day. Most of what we know about Callistus comes from a rather irate church theologian, Hippolytus of Rome, in the ninth book of his Refutation of All Heresies (you can probably guess how Hippolytus felt about Callistus based on the title alone). In his polemic against the bishop, Hippolytus threw the book at Callistus, accusing him of everything from trinitarian heresy to moral wantonness. For instance, Callistus had the gall to readmit mortal sinners into the church once they had done penance. He also recognized marriages between free women and enslaved men—gasp! But such ethical laxity was to be expected from someone like Callistus, Hippolytus reasoned—after all, Callistus was himself a former runaway slave.

Credentials Controversies, Then and Now

Just last month, the Southern Baptist Convention gathered in New Orleans for what promised to be another consequential meeting addressing, among other things, the ouster of churches that had women on staff as pastors and how to prevent such churches from infiltrating the denomination in the future. The Convention ended with a bang as the removal of two churches at the forefront of the debate, Saddleback and Fern Creek, was confirmed. The Convention also passed a motion amending the SBC constitution to require churches to restrict appointing or employing a woman as “a pastor of any kind.” Finally, messengers voted to make a substantial change to the guiding theological document of Southern Baptists, the Baptist Faith and Message. Article VI, which outlines church governance, was amended to say that “while both men and women are gifted for service in the church, the office of pastor/elder/overseer is limited to men as qualified by scripture.”

All three of these moves were aimed at restricting churches from ordaining women and kicking out those who already had. Denominational figures defending these decisions assert that the SBC is simply summarizing the Bible’s clear teaching. Denny Burk, the director of The Center for Gospel and Culture at Boyce College, wrote that the Baptist Faith and Message was “based on what the Bible says in texts like 1 Timothy 2:12, 3:2, and Titus 1:6.” He goes on to say that critics of the SBC’s policies don’t “give any sustained attention to 1 Timothy 3:2” which says that “those who hold the leadership office must be the ‘husband of one wife’” [i.e., they must be a man]. Reflecting on his role in the debates on the floor of the Convention, Southern Baptist Theological Seminary president Al Mohler said that “when you look at 1 Timothy, you look at Titus, you see clear affirmation of the fact that it is men who are to hold this teaching office…it is men who meet the scriptural qualifications and in whom the congregation recognizes the call to that office.”

It’s interesting that 1 Timothy 3 has been deployed frequently in the SBC’s polemic against women pastors, in part because that passage is the site of another, older debate within Christianity about who can seek the pastorate. The question at stake for many church leaders in the first and second centuries was not, Can a woman be ordained as a pastor? Rather, it was

Can a slave be installed as a bishop?

As irrelevant, odd, and even offensive as that question may sound to our ears, it was indeed a live one in the early Christian communities. The question was so live, in fact, that a New Testament epistle weighed in on the matter in the latter part of the first century. The pastoral letter of 1 Timothy appears to have been composed in part to address the matter of women or enslaved persons taking leadership roles in the church in Ephesus. In the third chapter, the author writes that

[W]hoever aspires to the office of bishop desires a noble task. Now a bishop must be above reproach, married only once, temperate, sensible, respectable, hospitable, an apt teacher, not a drunkard, not violent but gentle, not quarrelsome, and not a lover of money. He must manage his own household well, keeping his children submissive and respectful in every way— for if someone does not know how to manage his own household, how can he take care of God’s church? He must not be a recent convert, or he may be puffed up with conceit and fall into the condemnation of the devil. Moreover, he must be well thought of by outsiders, so that he may not fall into disgrace and the snare of the devil. (1 Tim. 3:1-7, NRSV)

Do you see what I see? Look closer. If you blink, you’ll miss it, but notice that in this passage the maleness of the bishop is bound up with another, more important qualifier—the socioeconomic status of the bishop. The author takes a clear stand in favor of restricting leadership, not just to men, but specifically to those men who were already upstanding citizens in Ephesus.

In Enslaved Leadership in Early Christianity, Katherine Shaner identifies the parallels between the list of qualifications in 1 Timothy and civic life in a Roman city. She writes that, for the author of 1 Timothy, “Bishops should embody free status, education, and high social positioning,” similar to candidates for civic office in Ephesus. “Such virtues,” she continues, “describe elite male citizens whose benefactions and civic service garner honor. They are virtues that precluded enslaved or formally enslaved persons from holding honorable positions.” (Shaner, 93-94) Jennifer Glancy agrees: “a man was eligible for consideration as a church leader if he had already demonstrated his ability to maintain discipline within his own household” and that “[m]anagement of household slaves was a basic element of home economics.” When we read the qualifications for bishops in 1 Timothy accounting for Romans’ sharp class distinctions, it becomes clear that the virtues listed only work on the assumption of free status. Just a few:

In Enslaved Leadership in Early Christianity, Katherine Shaner identifies the parallels between the list of qualifications in 1 Timothy and civic life in a Roman city. She writes that, for the author of 1 Timothy, “Bishops should embody free status, education, and high social positioning,” similar to candidates for civic office in Ephesus. “Such virtues,” she continues, “describe elite male citizens whose benefactions and civic service garner honor. They are virtues that precluded enslaved or formally enslaved persons from holding honorable positions.” (Shaner, 93-94) Jennifer Glancy agrees: “a man was eligible for consideration as a church leader if he had already demonstrated his ability to maintain discipline within his own household” and that “[m]anagement of household slaves was a basic element of home economics.” When we read the qualifications for bishops in 1 Timothy accounting for Romans’ sharp class distinctions, it becomes clear that the virtues listed only work on the assumption of free status. Just a few:

- married (sexual unions between enslaved persons or enslaved men united to free women were not recognized as marriages)

- one who manages his household well, i.e., a householder, a paterfamilias (slaves, by definition, would not qualify)

- hospitable (an enslaved person could potentially offer hospitality on behalf of his or her dominus or domina, but hospitality would have been attributed to the householder)

- a good reputation with outsiders (reputability was the luxury of a citizen. Sandra Joshel writes that “Enslaved people had no physical integrity and honor. Unlike the freeborn, slaves could not personally suffer iniuria— at least in the view of Roman lawyers. In cases that involved a slave, the honor of the slaveholder was abused by what amounted to an assault on an extension of himself.”)

Shaner sees 1 Timothy as one voice in an ongoing conversation on the status of enslaved Christians in antiquity. First Timothy and other early Christian texts, she argues, were attempts to regulate the positions of socially subordinated persons in the churches. The argument against enslaved leadership emerged out of pragmatic concerns, such as avoiding blowback from neighbors and authorities, but also out of an ancient Mediterranean culture that assumed the necessity of slavery. Yet there were clearly some—if few—authorities who were willing to install enslaved or freedpersons as bishops. For Shaner, the fact that 1 Timothy gives proscriptions against enslaved leaders suggests that such persons were in fact leading churches in Asia Minor, that 1 Timothy was written in part to “curb such practices.”

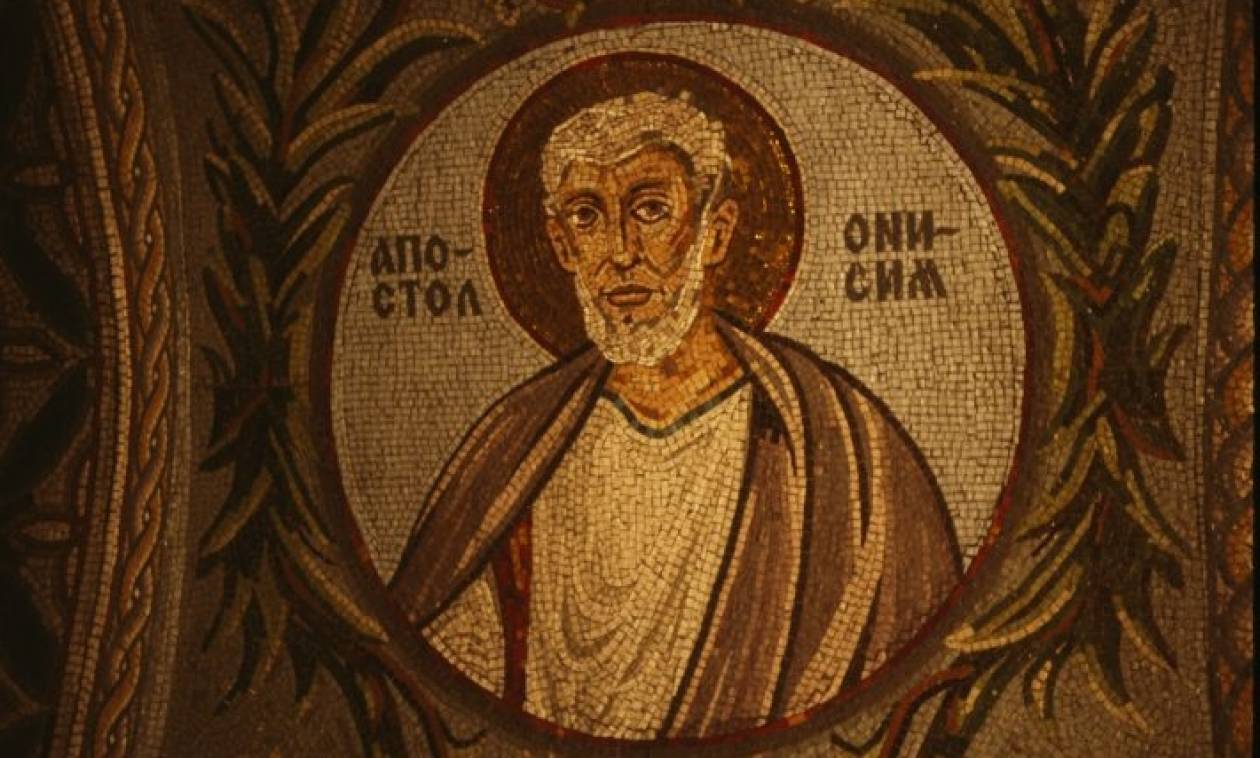

The instructions of the pastoral epistle are all the more striking when seen alongside the legacy of the most famous Christian slave of the first century, Onesimus. Onesimus is the subject of the Paul’s brief letter to Philemon written the 50s. Paul’s letter is not a theological treatise or a set of instructions to a church. Rather, it is a letter sent to accompany a slave, Onesimus, whom Paul is sending back to his householder, Philemon. He writes to convince Philemon to accept Onesimus back into the home without punishment and, some (including myself) argue, to manumit Onesimus from bondage. Mary Ann Beavis has written extensively on the legacy of Onesimus. According to Beavis, tradition holds that Onesimus became the bishop of Ephesus, being venerated for centuries as the patron saint of slaves. The slave Onesimus’s bishopric (real or not) gave a precedent for ordination in the 3rd century Apostolic Canons. The Canons stated that although slaves were not the ideal candidates for ministry, because their leaving would “grieve those that owned them” and “occasion the subversion of families”, still exceptional slaves could be received, “as our Onesimus appeared,” if their masters were willing to free them. (Beavis, 89)

(How interesting that the Canons simultaneously uphold the assumed power structures of Syrian Rome, warning against the subversion of family authority, and create space for that structure’s very subversion, putting in place the possibility that a freed slave may become the spiritual authority of his former master. Truly fascinating!)

In Christianity in the Roman Empire, the selection of a lower-class, enslaved, or freed person to a bishopric could be highly controversial. Introspective churchmen in late antiquity assumed that the ideal bishop’s training would be like that of Moses: brought up first in wealth and with the finest worldly education, and then called to renounce that background in the service of God’s people. (Rapp, 125-136) Claudia Rapp’s Holy Bishops in Late Antiquity points to some wealthy freeborn bishops who decried the election of former slaves and derided their fellow ministers of lower station.

For instance, Gregory of Nazianzus singled out a collection of his enemies, bishops who “come from the plough and are parched by the sun” or “have not yet completely washed away from their body the soot of their work at the fires[.]” Churchmen from such socio-economic situations were “worthy of a whipping or of laboring in the mills.” Gregory begrudgingly defended the installation of an enslaved person that had been overseen by Basil the Elder. Gregory sought to placate the slave’s master, Simplicia, by requesting that she file formal charges so that Gregory might censure and denounce his fellow bishop through the proper channels, since “by no means does he number among my friends or those who have done right by me.” (Ep. 79, trans. Bradley Storin) Or take Basil the Elder’s son, Basil of Caesarea, who referred to lower-class bishops as “slaves of slaves.” (Rapp, 174) For Hippolytus of Rome, Bishop Callistus’s early life as a slave—including his attempt to flee from his master—were revelatory of his ignoble character and heretical doctrine. By the time of Emperor Valentinian III (r. 425-455), there were laws in place regulating the consecration of enslaved bishops. Yet even then, there was a prominent fear that slaves would seek ordination to elevate themselves and “evade the yoke of their birth status.”

Context is King (or Bishop)

What’s the upshot of this discussion for Southern Baptists and broader evangelical debates over pastoral qualifications? Well, for one, I think in our rush to make the Bible applicable, we’re often tempted to wash over the cultural differences between us and ancient Christians. Such an ahistorical approach might be useful in the short-term, but it’s ultimately problematic for understanding the Bible.

For instance, Article VI of the Baptist Faith & Message assumes that what matters for pastoral qualification in 1 Timothy is 1) a man who 2) is godly. A biological man is the baseline qualification in this account. How you decide whether a man is godly, it’s presumed, is summarized in the list of virtues given. When we look at the context it becomes obvious that’s not all there is to it. What went without saying in the first century is that those virtues weren’t accessible to just any person with an X and Y chromosome. In fact, class functionally limited the criteria in more important ways than gender. This was true not only in the idealized church of Ephesus in 1 Timothy, but it was generally true in the churches of antiquity writ large.

At the same time, it’s clear that there was considerable flexibility within the ancient churches—that different expectations, traditions, and experiences shaped various leaders to respond to the needs of their communities differently than the pastor of 1 Timothy. The shared default assumption was that bishops would come from freeborn stock and have a certain pedigree. Practically speaking, however, whether an enslaved or freed person could receive ordination was negotiable. (We know this is true of women’s ordination too. For a good start, see Kevin Madigan and Carolyn Osiek’s work.) For rhetorical reasons, 1 Timothy presents a setting where the civic and religious social boundaries were synonymous and impermeable. As we look at the evidence across the empire and especially as the church situation changed, it’s clear that the composition of church leadership was much more varied.